Books for Children

In 1941, thirteen-year-old Alice’s days are filled with swimming in the Hawaiian sea, going to school, and helping watch her younger siblings. But on December 7th, everything changes when she experiences an act of war, the bombing of Pearl Harbor. As the United States enters World War II, Alice’s father is sent to a Japanese internment camp, leaving Alice and the rest of her family struggling to adjust to life without him. This girls survival story takes readers to one of history’s most important moments.

During World War II a community called Manzanar was hastily created in the high mountain desert country of California, east of the Sierras. Its purpose was to house thousands of Japanese American internees. One of the first families to arrive was the Wakatsukis, who were ordered to leave their fishing business in Long Beach and take with them only the belongings they could carry. For Jeanne Wakatsuki, a seven-year-old child, Manzanar became a way of life in which she struggled and adapted, observed and grew. For her father it was essentially the end of his life. At age thirty-seven, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston recalls life at Manzanar through the eyes of the child she was. She tells of her fear, confusion, and bewilderment as well as the dignity and great resourcefulness of people in oppressive and demeaning circumstances. Written with her husband, Jeanne delivers a powerful first-person account that reveals her search for the meaning of Manzanar.

In 1986, Henry Lee joins a crowd outside the Panama Hotel, once the gateway to Seattle’s Japantown (present day Chinatown in the International District.) It has been boarded up for decades, but now the new owner has discovered the belongings of Japanese families, left when they were rounded up and sent to internment camps during World War II. As the owner displays and unfurls a Japanese parasol, Henry, a Chinese American, remembers a young Japanese American girl from his childhood in the 1940’s, Keiko Okabe, with whom he forged a bond of friendship and innocent love that transcended the prejudices of their Old World ancestors. After Keiko and her family were evacuated first to Camp Harmony (the state fairgrounds at Puyallup that served as a temporary holding ground for Japanese American internees) and eventually to Camp Minidoka in Idaho, she and Henry could only hope that the war would end and that their promise to each other would be kept. Now, forty years later, Henry explores the hotel’s basement for the Okabe family’s belongings and for a long-lost object whose value he cannot even begin to measure. Now a widower, Henry’s search will take him on a journey to revisit the sacrifices he has made for family, for love, for country. The novel concludes with Henry’s son Marty locating Keiko in New York City, and Henry goes to see her.

Interview with author Jamie Ford by NPR News host Scott Simon in February 2009:

SIMON: One of the most arresting scenes in the book is when you describe the evacuation of Japanese-American families from Bainbridge Island.

FORD: At the time, it was a saw mill community and a farming community with a sizable Japanese population, but because it was self-contained and it was isolated, that was the first area that was evacuated. It was – you know, there was one bridge leading onto the island and then a ferry towards Seattle, so it was pretty easy for the Army to round everyone up, and it was almost an experiment in, was this feasible? How can we do this?

SIMON: How did you find out about the Panama Hotel in Seattle?

FORD: I was actually doing research on another story, about a nightclub in Chinatown called the Wami(ph), which is where my grandparents met. And when I was doing a little research, there was a mention of the hotel. And it was just intriguing enough. It was one of those stories that, you know, kind of captured my imagination. And the more I learned, the more amazed I was that not only did the hotel exist but that in the basement, there really were the belongings of all these Japanese families that had been taken away. And those belongings remain to this day.

SIMON: You know, I’m afraid we need to explain how those belongings wound up there.

FORD: Sure. You know, the tragic part is that people in the Japanese community were given just a few days to pack up, and they could only take, really, what they could carry. So they either sold things that – pays on the dollar, or they stored things with friends or neighbors, in the basements of churches, or the basements of hotels like the Panama.

The Panama Hotel (615 S. Main Street, Seattle ) is still a working hotel and a living museum filled with many items left behind by displaced Nikkei families. The items are displayed in the front window.

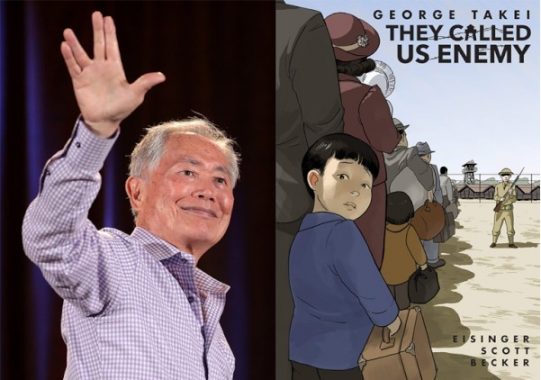

Actor, author, and activist George Takei has captured hearts and minds worldwide with his captivating stage presence and outspoken commitment to equal rights. But long before he braved new frontiers in Star Trek, he woke up as a four-year-old boy to find his own birth country at war with his father’s—and their entire family forced from their home into an uncertain future. In this graphic novel George Takei revisits his haunting childhood in American concentration camps, as one of 120,000 Japanese Americans imprisoned by the U.S. government during World War II.

Books for Adults

By 1968, Robert C. Sims had taught four years of high school history and was midway through his doctorate in history. Then he attended a lecture about the Japanese American confinement that followed the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. Despite his educational experience, he had never read or even heard about this tragic episode of American history, and it changed his life. Now considered by many to be the foremost scholar of the Minidoka Relocation Center, Sims, who died in 2015, devoted his career to research, writing, and education related to the unjust World War II Japanese American incarceration. An Eye for Injustice: Robert C. Sims and Minidoka, preserves his work and presents a passionate, academic perspective on the Idaho concentration camp.

Paul Kitagaki’s parents and grandparents were part of a group of 110,000 Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes during World War II, but they never talked about their experience. To better understand, Kitagaki tracked down the subjects of more than sixty photographs taken by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams and other photographers. Behind Barbed Wire: Searching for Japanese Americans Incarcerated During World War II is a result of Paul’s ten-year pilgrimage to track down surviving Japanese American subjects of these photographs. Using black-and-white film and a large-format camera similar to the equipment of photographers in the 1940s, Kitagaki sought to mirror and complement photographs taken during World War II—while revealing the strength and perseverance of the subjects.

He photographed and interviewed the subjects or their children to discover who was in the pictures. Some wanted to forget; some wanted to remember. Some lost everything; some found new direction. He heard stories about heroic soldiers and those unwilling to fight for a country that put them behind barbed wire. Each person has something to say. Each adds their unique personal history. They all are determined to make sure it never happens again.

One of the iconic photographs of the incarceration was of Fumiko Hayashida carrying her sleeping 13-month-old daughter Natalie to a waiting Bainbridge Island ferry. In 2006, Kitagaki caught up with the Hayashida family and took a photo of Fumiko and her daughter Natalie Kayo Ong on the Bainbridge Island farm where they lived before their forced removal.

During WWII most newspapers were silent on the Japanese American exclusion or else actively supported it. When the war was finally over, many West Coast communities tried to prevent their former neighbors from returning home. On Bainbridge Island it was just the opposite. Milly and Walt Woodward, editors of the little local paper The Bainbridge Review, consistently spoke out against the exclusion. They ran weekly accounts of significant events in the exiled Islanders’ lives, reported back by high school students–paid as correspondents–in the concentration camps. With the end of the war, the Woodwards and other Islanders welcomed their neighbors home with little incident.

In most West Coast communities the public positions of politicians and the media made it difficult for opponents to speak up. On Bainbridge Island it was the supporters of the exclusion who were apt to keep their opinions to themselves. In Defense of our Neighbors, a book by the Woodwards’ daughter, Mary, released in November 2008, records how The Review helped create an environment that was friendly to those who, like the editors, strongly opposed the exclusion.

Contemporary newspaper articles, oral histories of the exiles and other Islanders, and vivid photographs and images combine in this lively and visually attractive, history. A portion of the proceeds will benefit the Nidoto Nai Yoni–Let It Not Happen Again–Memorial.

Departures opens on the eve of Pearl Harbor and ends at the present-day Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial.

“I’m surprised at how many alert, well-educated people know little or nothing about this shameful episode in American history,” Dillon said. “Given the current political environment, I felt it was important to revisit the matter and offer fresh angles on what happened.”

Dillon’s Departures, Poetry and Prose On The Removal Of Bainbridge Island’s Japanese Americans After Pearl Harbor is a chronology of the removal for internment, or imprisonment as the book corrects, of 227 American Citizen’s of Japanese ancestry who lived on Bainbridge Island at the beginning of WWII. The discussion is at once historical, social, and personal, and the format shifts between poetry and prose.

Dillon was born after WWII as a fourth generation Bainbridge Islander and has no firsthand recollections of the removals, but it was a topic among his family and community–he grew up with the wrenching experience in Bainbridge as cultural memory.

In Looking After Minidoka, the camp years become a prism for understanding three generations of Japanese American life, from immigration to the end of the twentieth century. Nakadate blends history, poetry, rescued memory, and family stories in an American narrative of hope and disappointment, language and education, employment and social standing, prejudice and pain, communal values and personal dreams.

Through essays supplemented by 180 black-and-white photographs and interviews that fuse present and past, Teresa Tamura documents Minidoka, one of America’s ten concentration camps located in Jerome County, Idaho. Her documentation includes artifacts made in the camp as well as the story of its survivors, uprooted from their homes in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and California. Tamura began her project after President Bill Clinton designated part of the Minidoka site as the 385th unit of the National Park Service. In Minidoka: An American Concentration Camp, Tamura’s work furthers the tradition of socially inspired documentary photojournalism, illuminating the cultural, sociological, and political significance of Minidoka.

On December 7, 1941, forces of the Japanese Empire attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbor and left hundreds of American military members and civilians dead or wounded. In response to the surprise attack, the United States declared war on Japan the next day. The attack on America inflamed anti-Japanese sentiment and hysteria that led to hate crimes, particularly on the West Coast, against aliens and US citizens of Japanese extraction—and those who looked like them.

Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s February 1942 Executive Order 9066, the US government forcibly removed 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from their homes and incarcerated them in concentration camps.

The detainees included Hanae and Ernest Matsuda who, with removal in 1942, lost their home and grocery business in Seattle. Like thousands of others, they were evacuated without due process and were incarcerated at the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho where Hanae gave birth to two sons and a stillborn child.

Hanae and Ernest Matsuda’s youngest son Lawrence was born in 1945 in Block 26, Barrack 2, of Minidoka Camp. Their baby’s prisoner number was 11464d.

Now Dr. Lawrence Matsuda, a renowned Seattle writer and human rights activist, brings to life his mother’s travails, traumas, and triumphs in mid-20th century America in his debut historical novel My Name is Not Viola. The events experienced by the fictional Hanae of the novel mirror actual incidents in the life of his mother including her girlhood in Seattle’s Japantown; her pre-war journey to Hiroshima, Japan; her removal from her Seattle home and incarceration at the brutal Minidoka concentration camp; her quest for Hiroshima relatives after the atomic obliteration of the city; her marital woes; her severe depression and incarceration at Western State Hospital, a psychiatric facility; her resilience grounded in Japanese and western beliefs; and her evolution as a force for good.

The novel captures the rhythm of life in Seattle’s Japantown, the unrelenting misery of internment at the Minidoka camp, and the pain and loss of internees as they returned home after the war to face dispossession and poverty. This history through the eyes of the fictional Hanae grips the reader with its lively writing and evocative imagery while sharing an important and heartbreaking chapter from our American experience. Yet it is also a story of hope and triumph despite recurrent traumas—and quite timely as we face an unprecedented pandemic and political crises today.

Dr. Matsuda is known in Seattle as a voice for social justice, equality, and tolerance. He is a former secondary school teacher, administrator, principal, and professor. He received an MA and PhD at the University of Washington

San Piedro Island, a fictional island north of Puget Sound, is a place so isolated that no one who lives there can afford to make enemies. But in 1954 a local fisherman is found suspiciously drowned, and a Japanese American named Kabuo Miyamoto is charged with his murder. In the course of the ensuing trial, it becomes clear that what is at stake is more than a man’s guilt. For on San Piedro, memory grows as thickly as cedar trees and the fields of ripe strawberries–memories of a charmed love affair between a white boy and the Japanese girl who grew up to become Kabuo’s wife; memories of land desired, paid for, and lost. Above all, San Piedro is haunted by the memory of what happened to its Japanese residents during World War II, when an entire Japanese American community was sent into exile while its neighbors watched. Gripping, tragic, and densely atmospheric, Snow Falling on Cedars is a masterpiece of suspense– one that leaves us shaken and changed.

Author David Guterson was born in Seattle, WA and currently lives on Bainbridge Island. He taught at Bainbridge Island High School for 10 years before becoming a professional writer.

The 1942 wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans has come to be seen as one of the most massive violations of civil liberties in the history of American law. Racially motivated and fueled by a malicious campaign of misinformation, it forced 120,000 Americans to abandon their property and homes. Most were American citizens. One of the largest and most remote of America’s concentration camps was Idaho’s Camp Minidoka in Jerome County, near Twin Falls, ID. The story, tragic yet triumphant, raises enduring questions about racial profiling, military authority and the hysteria of war. This 200 page art book and tribute presents 10 intriguing essays in an elegant hardcover volume of poetry, rare prints, historical photography, and original artwork.

Surviving Minidoka is a history book about the present as much as the past. It is a book about how about how an event shaped race relations more than a story about the event itself.

In the spring of 1942, the United States rounded up 109,000 residents of Japanese ancestry living along the West Coast and sent them to detention centers for the duration of World War II. Many abandoned their land. Many gave up their personal property. Each one of them lost a part of their lives.

Amazingly, the government hired famed photographers Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, and others to document the expulsion—from assembling Japanese Americans at racetracks to confining them in ten camps spread across the country. Their photographs, exactly seventy-five years after the evacuation began, give an emotional, unflinching portrait of a nation concerned more about security than human rights. These photographs are more important than ever.

Authors Richard Cahan and Michael Williams—noted photo historians—took a slow, careful look at each of these images as they put together a powerful history of one of America’s defining moments. Their book consists of photographs that have never been seen, many of them impounded by the U.S. Army. It also uses primary source government documents to explain and place the pictures in context. And Un-American relies on firsthand recollections of Japanese Americans survivors to offer a complete perspective.