Tractor on Strawberry Farm

Japanese commanders surrendered their swords to the Allies aboard the USS Missouri in a traditional ceremony September 2, 1945; nearly a month after the atom bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in southern Japan where most Island Nikkei families originated. Kay Nakao and her sisters and brother lost their grandmother in the Hiroshima devastation.

Since the European Axis powers had surrendered in May, with this Pacific ceremony, World War II officially ended. By that time, most exiled Nikkei had been released from confinement and allowed to return to the West Coast. Following the Endo case before the Supreme Court and with the end of war in sight, the government released the first Nikkei in January 1945.

Islanders Sam Nakao and Johnny Nakata visited Bainbridge Island in the spring to determine if it was a safe environment for their young families. Both were satisfied and brought their families homes, following the example set by Saichi and Yone Takemoto, who in April became the first Islanders to return.

Slideshow

Rebuilding Lives After War: A collection of artifacts and photos chronicling Bainbridge Island Nikkei after the end of WWII

At the close of the war the group of 276 Bainbridge Islanders of Japanese ancestry who were forced to leave the island in March 1942 were scattered across the country and world. One hundred twenty–three were in Minidoka, twenty–six in Manzanar, forty–four were serving in the armed forces in the states and abroad, and still others had left the camps to seek employment or education in areas outside of the exclusion zone. This close–knit Japanese farming community, like many others across the western states, had been drastically altered by exclusion and detention.

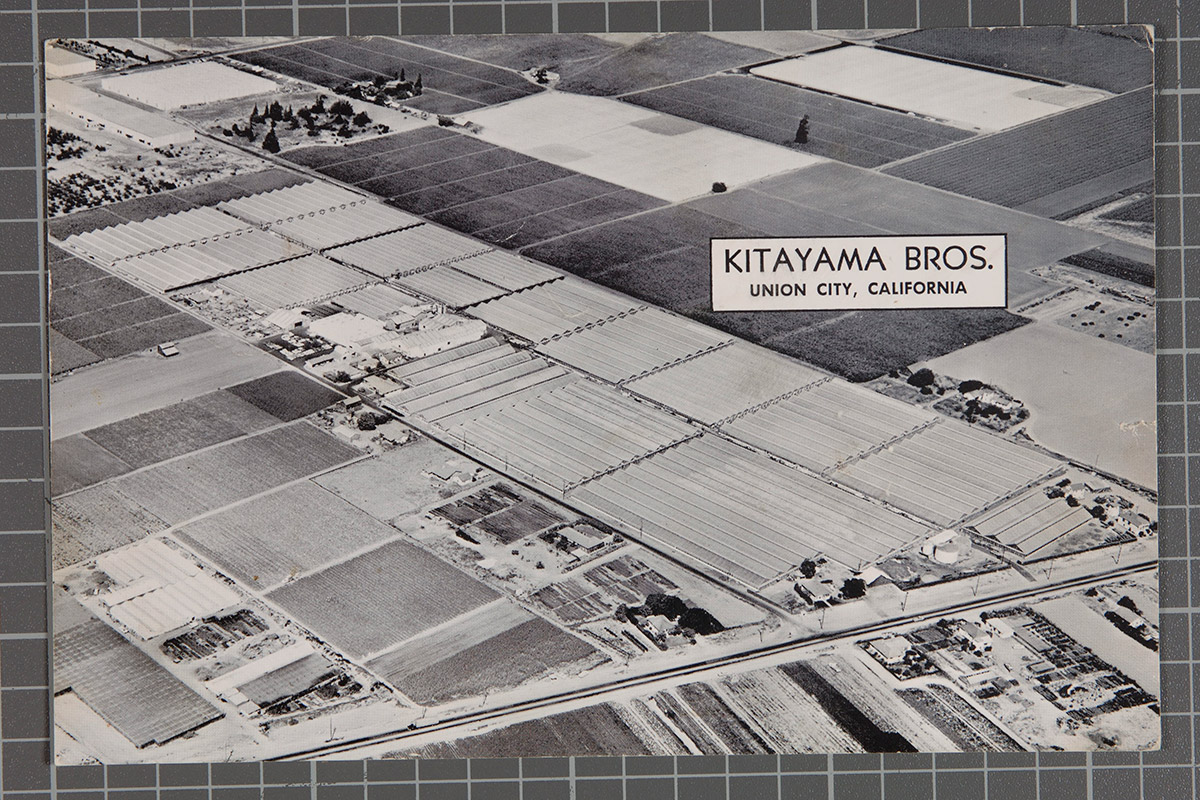

Many Island families did not return to Bainbridge because they had rented their homes and land and had nothing to return to. Others who had left the camps to move east during the war had started new lives and remained there. The Sakumas chose to settle in the nearby Burlington area where they felt the land was more farmable. The Kinos lost their strawberry farm when taxes could not be paid and thus could not return. The Kitayamas started a prosperous greenhouse business in California. Even though they did not return to Bainbridge Island, most remained in close contact with their Island friends and stayed abreast of news from "back home" for years to come.

Over half of the families did return to Bainbridge Island after the war and were successful in rebuilding their lives and businesses. All of them are grateful to the Woodwards and the role that the Review played in helping to create an accepting and peaceful atmosphere for them to come home to. Throughout the war the Woodwards printed columns with news of daily events that occurred in the lives of the Bainbridge Island Nikkei who, though forced to leave the island, still called it home. They were not forgotten while away. Also instrumental in promoting this welcoming environment was the Open Forum through which Islanders could express their feelings in letters to the editor. Letters in opposition to the return of the Japanese were printed but this just seemed to spur more letters in support of their return. Bainbridge Island did not have a corner on the market for this type of supportive sentiment, but the Review helped bring it to a public platform where the beliefs of individuals could be shared with the entire community. The Island Nikkei returned without fanfare but also without any resistance.

Home of Greenleaf Wholesale Florists, Inc. Over 35.5 acres of flower greenhouses, specializing in roses and carnations. Union City, CA. 1967. Following the war, Tsutomu and Isamu Kitayama moved to San Leandro, CA and started a greenhouse business. Years later their business grew to this operation.

Home of Greenleaf Wholesale Florists, Inc. Over 35.5 acres of flower greenhouses, specializing in roses and carnations. Union City, CA. 1967. Following the war, Tsutomu and Isamu Kitayama moved to San Leandro, CA and started a greenhouse business. Years later their business grew to this operation. The Kobas and Tad Sakumas lived and farmed here after the war. They eventually returned to Bainbridge Island in 1947. (Credit: Gary Sakuma Collection)

The Kobas and Tad Sakumas lived and farmed here after the war. They eventually returned to Bainbridge Island in 1947. (Credit: Gary Sakuma Collection) The Hayashidas take one last photo at the gate to Minidoka before they leave for the trip home to Bainbridge Island. Left to right. Back: Fumiko, Tomiko, Nobuko, Ichiro. Front: Mamoru, Yasuko, Toyoko, Hisako, Hiroshi.

The Hayashidas take one last photo at the gate to Minidoka before they leave for the trip home to Bainbridge Island. Left to right. Back: Fumiko, Tomiko, Nobuko, Ichiro. Front: Mamoru, Yasuko, Toyoko, Hisako, Hiroshi. This bag was owned by Nobuo Moritani and was most likely used when he traveled from Minidoka back home to Bainbridge Island at the end of the war. The Moritani brothers ran a successful Olympic Berry farming operation in Winslow on Bainbridge Island for many years following the war.

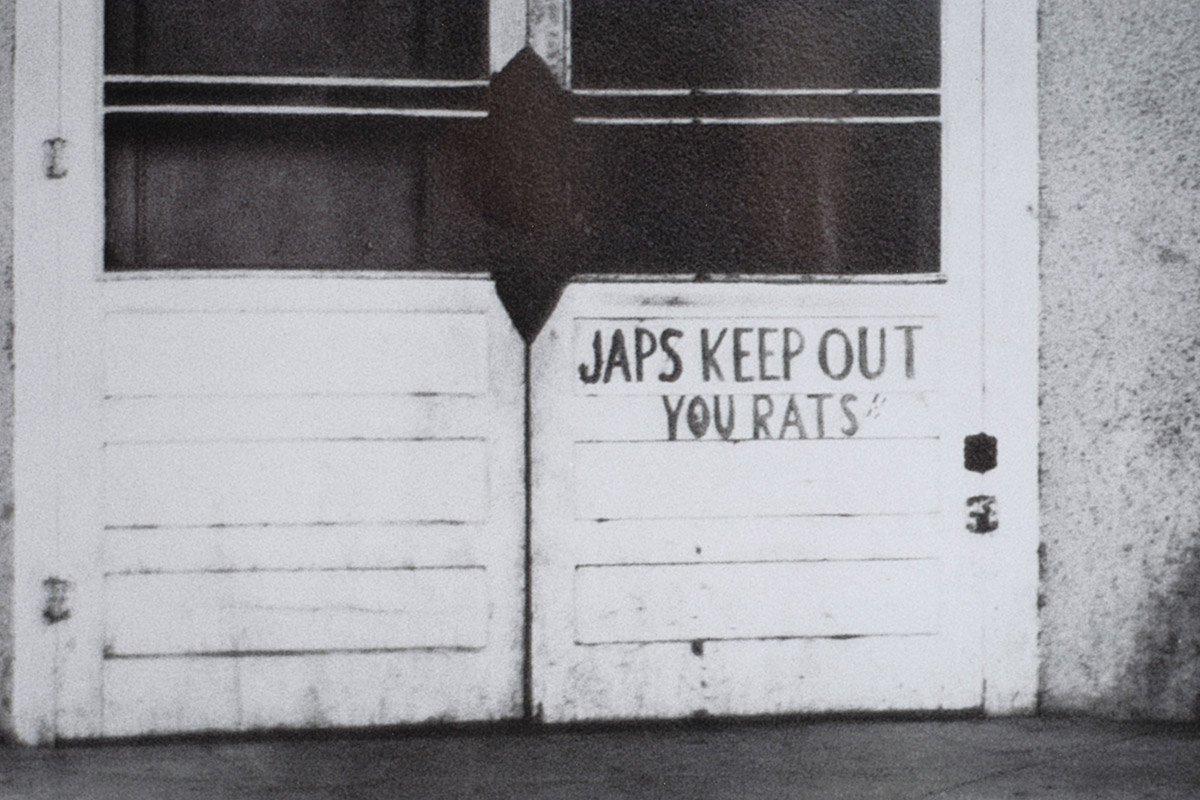

This bag was owned by Nobuo Moritani and was most likely used when he traveled from Minidoka back home to Bainbridge Island at the end of the war. The Moritani brothers ran a successful Olympic Berry farming operation in Winslow on Bainbridge Island for many years following the war. This is the type of welcome many Japanese Americans faced upon return from being exiled. (Credit: National Archives and Records Administration)

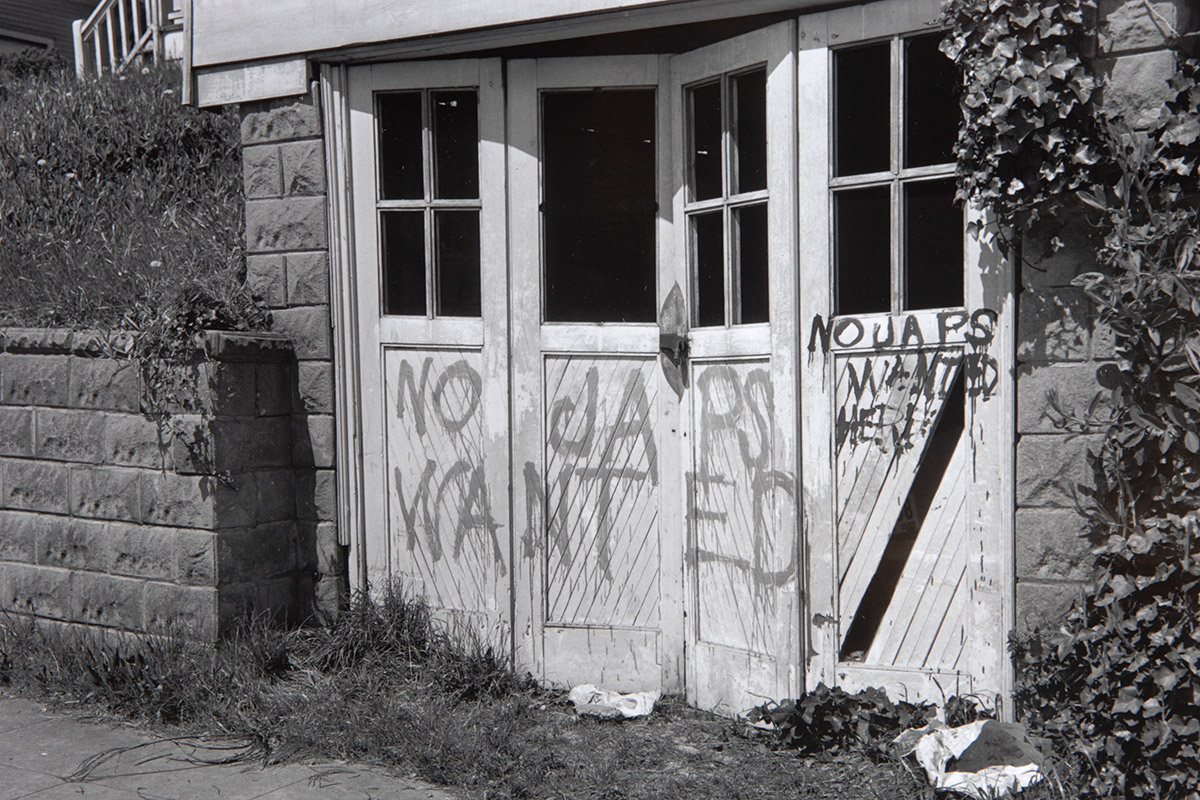

This is the type of welcome many Japanese Americans faced upon return from being exiled. (Credit: National Archives and Records Administration) The Nikkei of Bainbridge Island were lucky not to see such open racism in their community upon their return home. (Credit: Museum of History and Industry. Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection)

The Nikkei of Bainbridge Island were lucky not to see such open racism in their community upon their return home. (Credit: Museum of History and Industry. Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection) Lambert Schuyler was one of the few who lobbied to prevent the return of the Japanese Americans to Bainbridge Island. He printed this book in an attempt to gain support for his campaign but after the curiosity of folks who attended a few meetings wore off, it was clear that he was in the minority on Bainbridge Island.

Lambert Schuyler was one of the few who lobbied to prevent the return of the Japanese Americans to Bainbridge Island. He printed this book in an attempt to gain support for his campaign but after the curiosity of folks who attended a few meetings wore off, it was clear that he was in the minority on Bainbridge Island. Years later, in 1985, Ethan Schuyler, Lambert's son, wrote a formal apology to the Japanese community on Bainbridge Island on behalf of his father. In an open letter to Islanders published in the Review he wrote, "In the years following the war, my father regretted his impulsive actions as he came to personally know, respect, and trust many of the imprisoned Americans."

Years later, in 1985, Ethan Schuyler, Lambert's son, wrote a formal apology to the Japanese community on Bainbridge Island on behalf of his father. In an open letter to Islanders published in the Review he wrote, "In the years following the war, my father regretted his impulsive actions as he came to personally know, respect, and trust many of the imprisoned Americans." The Koura brothers returned to farming on Bainbridge Island following the war. In retirement they sold most of their land to developers. This land is part of the Meadowmeer Golf Course and Koura Farms development off of Koura Road.

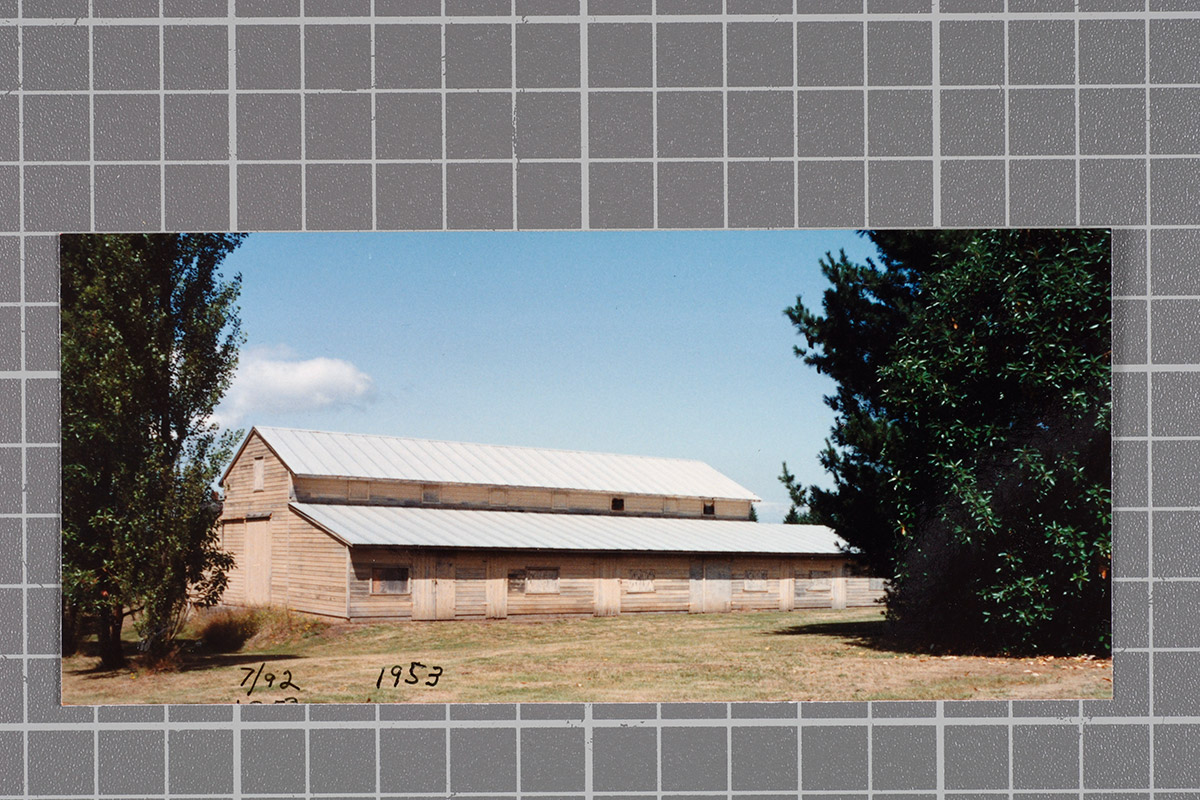

The Koura brothers returned to farming on Bainbridge Island following the war. In retirement they sold most of their land to developers. This land is part of the Meadowmeer Golf Course and Koura Farms development off of Koura Road. Built in the late 1930s, this bunkhouse was used by berry pickers and farmhands who helped run the Koura farm.

Built in the late 1930s, this bunkhouse was used by berry pickers and farmhands who helped run the Koura farm. Originally built circa 1950. Bainbridge Island, WA.

Originally built circa 1950. Bainbridge Island, WA. Built following the war in the 1950s, these cabins housed seasonal berry pickers.

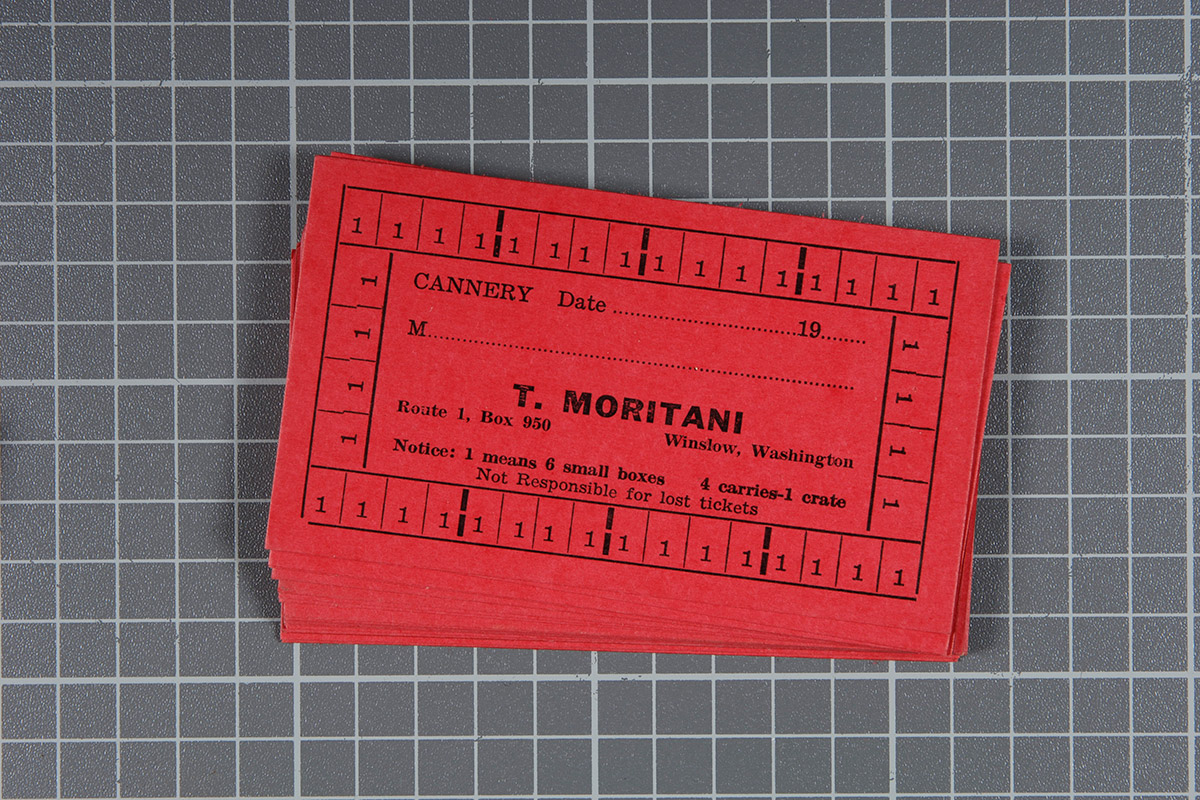

Built following the war in the 1950s, these cabins housed seasonal berry pickers. For the T. Moritani farm. This card was held by each berry picker to keep track of how much they had picked. The card was hole-punched for each small box of strawberries picked.

For the T. Moritani farm. This card was held by each berry picker to keep track of how much they had picked. The card was hole-punched for each small box of strawberries picked. These handmade wooden carriers were used in the fields to bring boxes of strawberries to collection points or the packing sheds out in the fields. (Credit: Bainbridge Island Historical Society)

These handmade wooden carriers were used in the fields to bring boxes of strawberries to collection points or the packing sheds out in the fields. (Credit: Bainbridge Island Historical Society) The Kojima family did not return to Bainbridge Island. The three girls and their father moved to Salt Lake City, UT and their brother went to Chicago, IL.

The Kojima family did not return to Bainbridge Island. The three girls and their father moved to Salt Lake City, UT and their brother went to Chicago, IL. Following the war, Fumiko (left) and her husband decided to move to Seattle where he got a job at Boeing. Shigeko (center) and her family moved back into the family home on BI. Her husband opened a jewelry store in Seattle and she ran the farm. Nobuko (right) and her family also remained on Bainbridge where her husband got the Hayashida Brothers' farm going again.

Following the war, Fumiko (left) and her husband decided to move to Seattle where he got a job at Boeing. Shigeko (center) and her family moved back into the family home on BI. Her husband opened a jewelry store in Seattle and she ran the farm. Nobuko (right) and her family also remained on Bainbridge where her husband got the Hayashida Brothers' farm going again. For the children, returning to school after a three-year absence was a bit scary. But, there are several tales of other youngsters welcoming them back, sitting with them on the bus, and resuming old playground friendships. Here the Hayashidas (two families) pose for a photo in front of their home located off of High School Road.

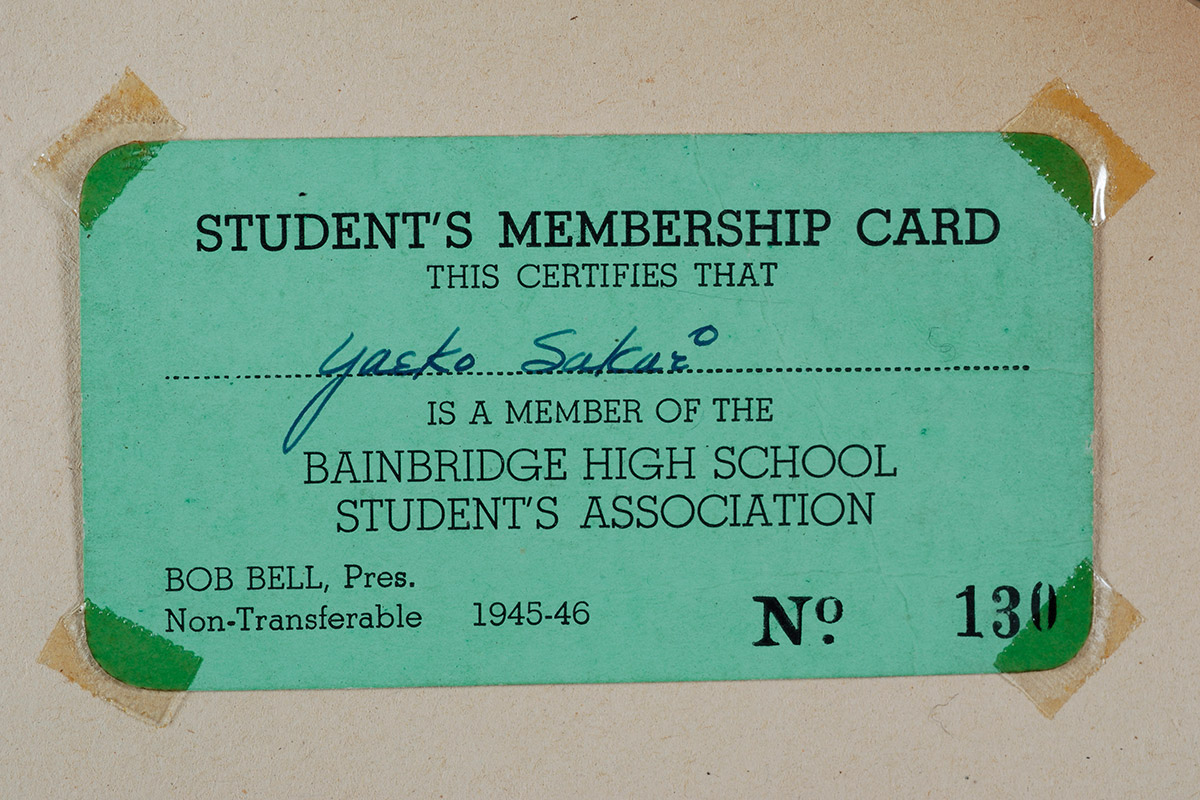

For the children, returning to school after a three-year absence was a bit scary. But, there are several tales of other youngsters welcoming them back, sitting with them on the bus, and resuming old playground friendships. Here the Hayashidas (two families) pose for a photo in front of their home located off of High School Road. For the older students, returning to junior high and high school on Bainbridge Island was also a smooth transition. Though less in numbers than before the war, the Japanese Americans soon became involved in many school sports and activities. Socially, they resumed old friendships that in many cases lasted a lifetime.

For the older students, returning to junior high and high school on Bainbridge Island was also a smooth transition. Though less in numbers than before the war, the Japanese Americans soon became involved in many school sports and activities. Socially, they resumed old friendships that in many cases lasted a lifetime. Though Reverend Hirakawa did not return to the Island following the war, part of the Winslow Lighthouse Church he had built from 1925-27, a single room building, remained for years where many Issei services such as this one were held.

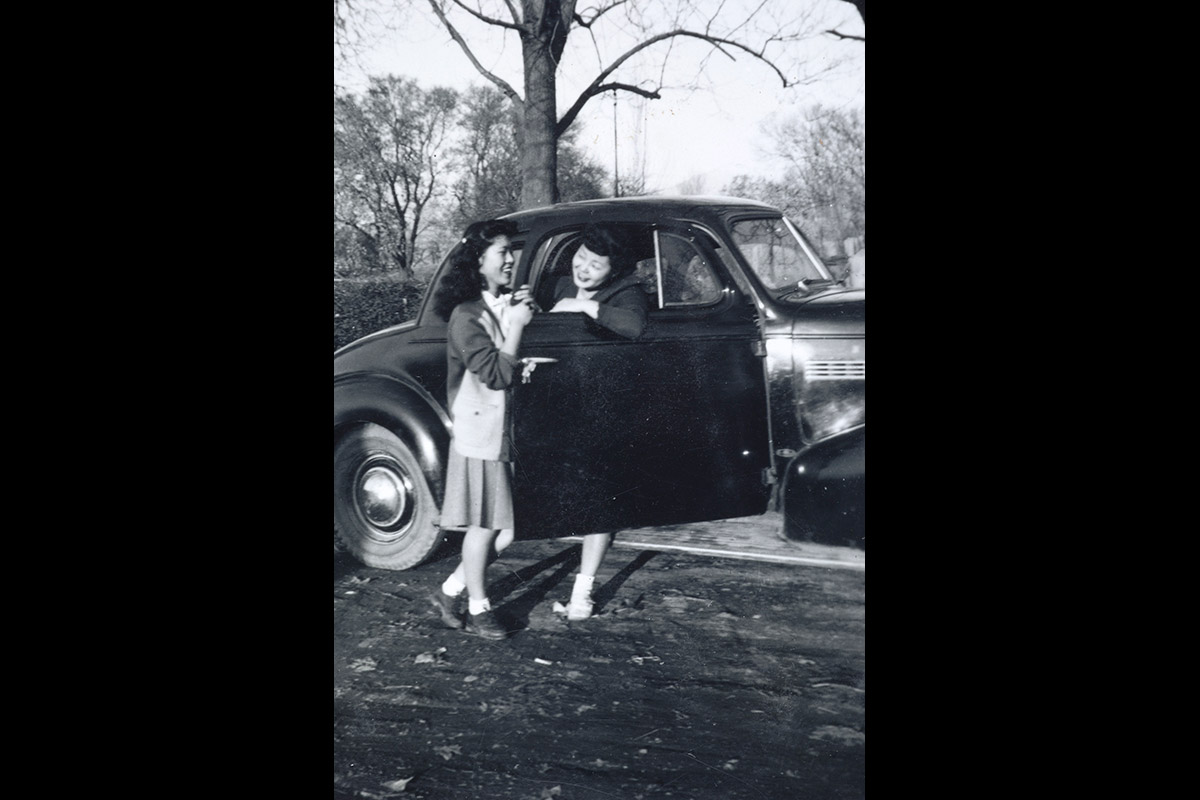

Though Reverend Hirakawa did not return to the Island following the war, part of the Winslow Lighthouse Church he had built from 1925-27, a single room building, remained for years where many Issei services such as this one were held. Bonds strengthened by the common experiences of exile and detention forged strong friendships amongst the Island's Nisei. Though many did not return to the island after the war, most still remain in contact today and return to Bainbridge Island for reunions and community picnics.

Bonds strengthened by the common experiences of exile and detention forged strong friendships amongst the Island's Nisei. Though many did not return to the island after the war, most still remain in contact today and return to Bainbridge Island for reunions and community picnics. Resuming the annual tradition of summer Japanese community picnics was an important part to making the Nikkei feel at home back on Bainbridge Island. These picnics still occur every other summer today.

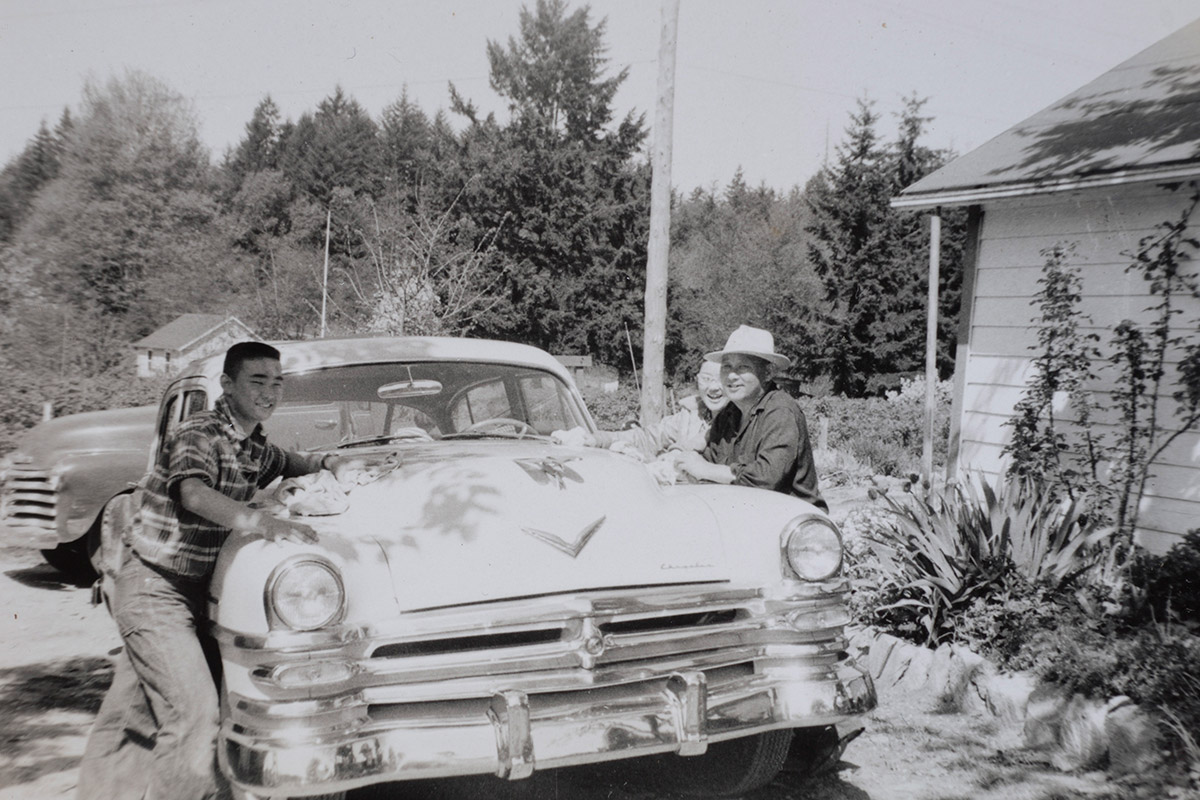

Resuming the annual tradition of summer Japanese community picnics was an important part to making the Nikkei feel at home back on Bainbridge Island. These picnics still occur every other summer today. Many Nisei and Sansei youth tried their best to be as "American" as possible, perhaps still trying to prove their loyalty to their country. Some changed their names, such as "Yoshikazu" became "Frank" (left) and "Chiseko" became "Jane" (back right). How they dressed, what they ate, and what activities they chose to do all reflected this typical American lifestyle of the 50s.

Many Nisei and Sansei youth tried their best to be as "American" as possible, perhaps still trying to prove their loyalty to their country. Some changed their names, such as "Yoshikazu" became "Frank" (left) and "Chiseko" became "Jane" (back right). How they dressed, what they ate, and what activities they chose to do all reflected this typical American lifestyle of the 50s. Seattle WA. Mar 8, 1958. 617 Jackson St. Seattle, WA. During the war Frank attended Jeweler's School in Chicago while his family was in Minidoka. He opened this store following the war.

Seattle WA. Mar 8, 1958. 617 Jackson St. Seattle, WA. During the war Frank attended Jeweler's School in Chicago while his family was in Minidoka. He opened this store following the war.

Oral History

- Help from nurse from Winslow clinic, restart farm - Michi Noritake (OH0011)

- Help from Reverend Andrews - Vic Takemoto (OH0017)

- Getting renter out, looking over shoulder - Kay Nakao (OH0023)

- Conditions of family farm upon return, going back to school - Yae Yoshihara (OH0041)

- Supportive community - Frank Kitamoto (OH0046)

- Bainbridge Gardens - Junkoh Harui (OH0059)

- Returning to school - Sally Kitano (OH0073)

- Discrimination - Sally Kitano (OH0074)

- Memorial on Bainbridge Island - Sada Omoto (OH0095)