Four Boys at Bainbridge Gardens

In the 1930's Bainbridge Island was a sleepy cluster of communities each with its own post office, gathering spot, and grocery. A "mosquito fleet" of steamers darted from dock to dock, a relief from the awful condition of the dirt roads, often gutted by rains or dusty from the sun. Bainbridge High School, established in 1928 when two schools combined, served grades seven through twelve.

Perhaps as a result of the unifying effect of one high school, Bainbridge Island was beginning to see itself as a community. Immigrants who, fifty years earlier, separated themselves into homogenous neighborhoods, now were scattered across the Island. Slavs lived next door to Japanese; Italians were neighbors with Finns.

There was no longer a "Yama" or a "Dagotown." All Islanders were proud of the Island's largest industry: strawberry farming, producing two million pounds in 1940, all from Issei (first generation Japanese immigrant) farms. At the high school, Nisei (second generation Japanese) were student leaders in sports, academics and government. Close friendships grown from twelve years association in Island schools often crossed ethnic lines.

Slideshows

Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko (brothers with different last names because Zenmatsu took his wife's last name) became business partners in 1913 and began to build Bainbridge Gardens. The nursery soon grew into the beautiful ornamental gardens shown here.

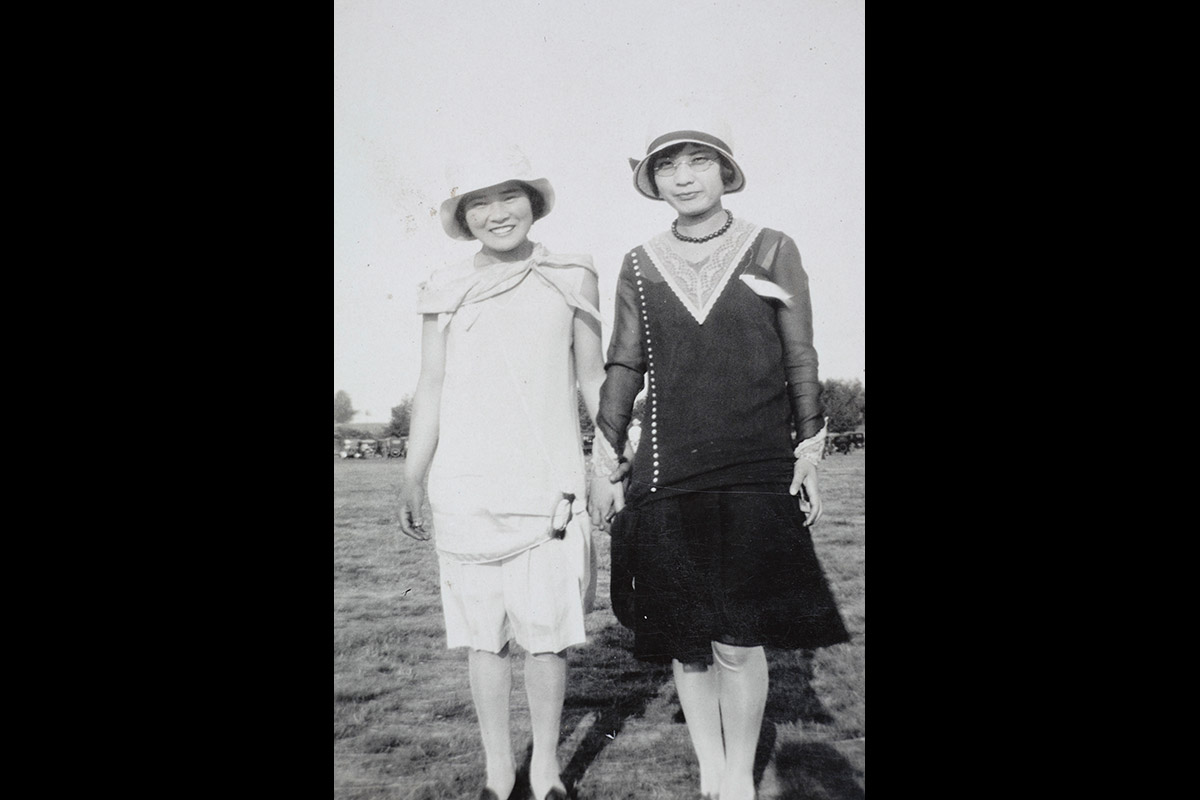

Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko (brothers with different last names because Zenmatsu took his wife's last name) became business partners in 1913 and began to build Bainbridge Gardens. The nursery soon grew into the beautiful ornamental gardens shown here. Yaeko Yamashita and Fujiko Koba stand in one of the rich and beautiful gardens that surrounded the grocery and nursery store.

Yaeko Yamashita and Fujiko Koba stand in one of the rich and beautiful gardens that surrounded the grocery and nursery store. Hatsuno Seko and Shiki Harui, wives of Zenmatsu Seko and Zenhichi Harui, stand in one of the Bainbridge Gardens greenhouses showing off their prize-winning chrysanthemums.

Hatsuno Seko and Shiki Harui, wives of Zenmatsu Seko and Zenhichi Harui, stand in one of the Bainbridge Gardens greenhouses showing off their prize-winning chrysanthemums. The gardens were a favorite spot for young children to play in. Top: Yoshiho Art Harui. Middle: unknown. Front, left to right: Norio Harui, Zenji Shibayama, Junkoh Harui.

The gardens were a favorite spot for young children to play in. Top: Yoshiho Art Harui. Middle: unknown. Front, left to right: Norio Harui, Zenji Shibayama, Junkoh Harui. This photo, taken circa '35-'41, shows how established and lush the gardens were. It is understandable that owners Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko were devastated upon their return after the war when they saw these gardens in ruins.

This photo, taken circa '35-'41, shows how established and lush the gardens were. It is understandable that owners Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko were devastated upon their return after the war when they saw these gardens in ruins. Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko procured 23 acres of land off of Miller Road where they built Bainbridge Gardens Grocery and Nursery along with several ornamental gardens, farmland for growing the plants for the nursery, and a home for their families.

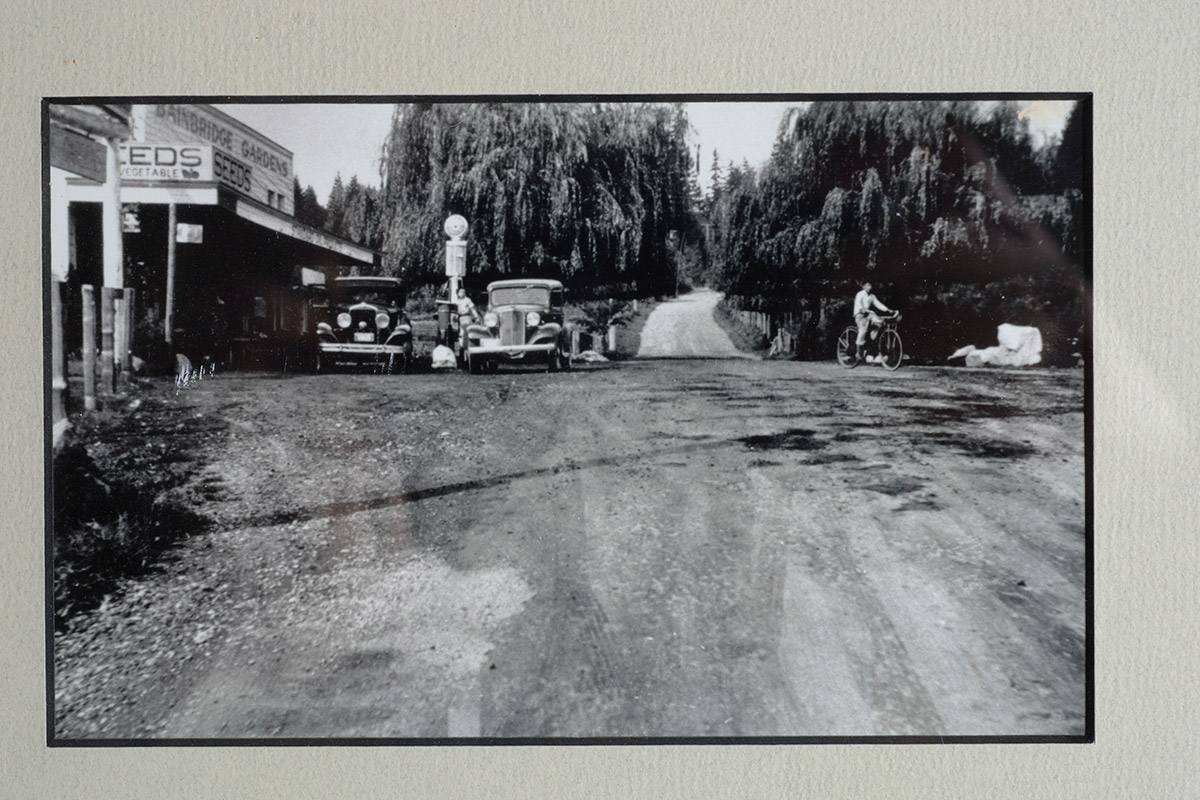

Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko procured 23 acres of land off of Miller Road where they built Bainbridge Gardens Grocery and Nursery along with several ornamental gardens, farmland for growing the plants for the nursery, and a home for their families. Miller Road runs through the middle of the property owned by Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko. To the left are the grocery and nursery stores. To the right was farmland where the nursery plants were raised.

Miller Road runs through the middle of the property owned by Zenhichi Harui and Zenmatsu Seko. To the left are the grocery and nursery stores. To the right was farmland where the nursery plants were raised. Before the war Bainbridge Island was made up of several small communities each with their own grocery store and post office. Bainbridge Gardens was in the heart of the Fletcher Bay community off of Miller Road. People would often gather here to visit with friends and neighbors.

Before the war Bainbridge Island was made up of several small communities each with their own grocery store and post office. Bainbridge Gardens was in the heart of the Fletcher Bay community off of Miller Road. People would often gather here to visit with friends and neighbors. Even gasoline was sold at Bainbridge Gardens. Here Shiki Harui and Hatsuno Seko are with one of Shiki's young sons.

Even gasoline was sold at Bainbridge Gardens. Here Shiki Harui and Hatsuno Seko are with one of Shiki's young sons. This thriving grocery was rented during the war. The tenants kept up the building so it was in good shape upon the Haruis and Sekos return after the end of the war.

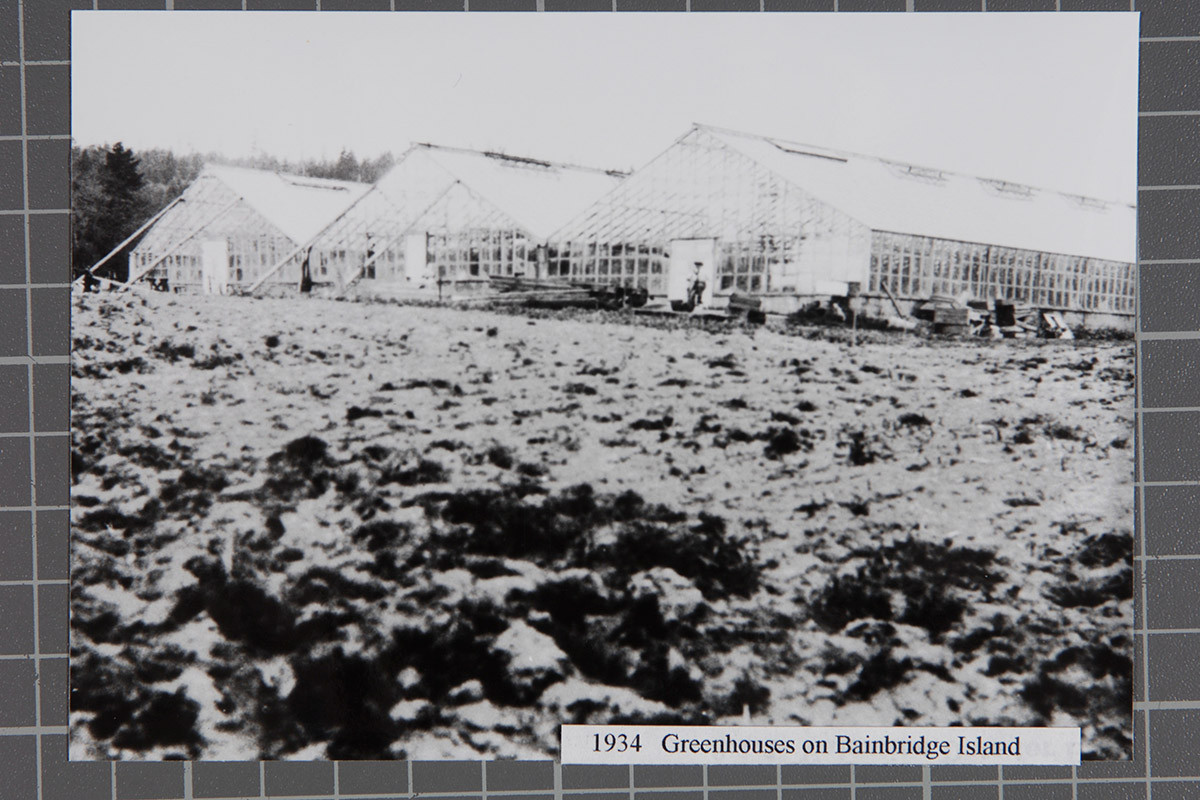

This thriving grocery was rented during the war. The tenants kept up the building so it was in good shape upon the Haruis and Sekos return after the end of the war. Upon their return after the end of the war, the Haruis and Sekos were devastated to find their gardens and nursery damaged beyond repair. The beautiful plants were stolen or had died, the display gardens were ruined, and the greenhouses had collapsed.

Upon their return after the end of the war, the Haruis and Sekos were devastated to find their gardens and nursery damaged beyond repair. The beautiful plants were stolen or had died, the display gardens were ruined, and the greenhouses had collapsed. Zenhichi Harui attempted to rebuild Bainbridge Gardens, but he was getting on in age and had little savings. He was never able to get the business back to where it was before the war. Thirty years later, his son Junkoh would finally re-build Bainbridge Gardens at this same location and today it is once again a beautiful and thriving business.

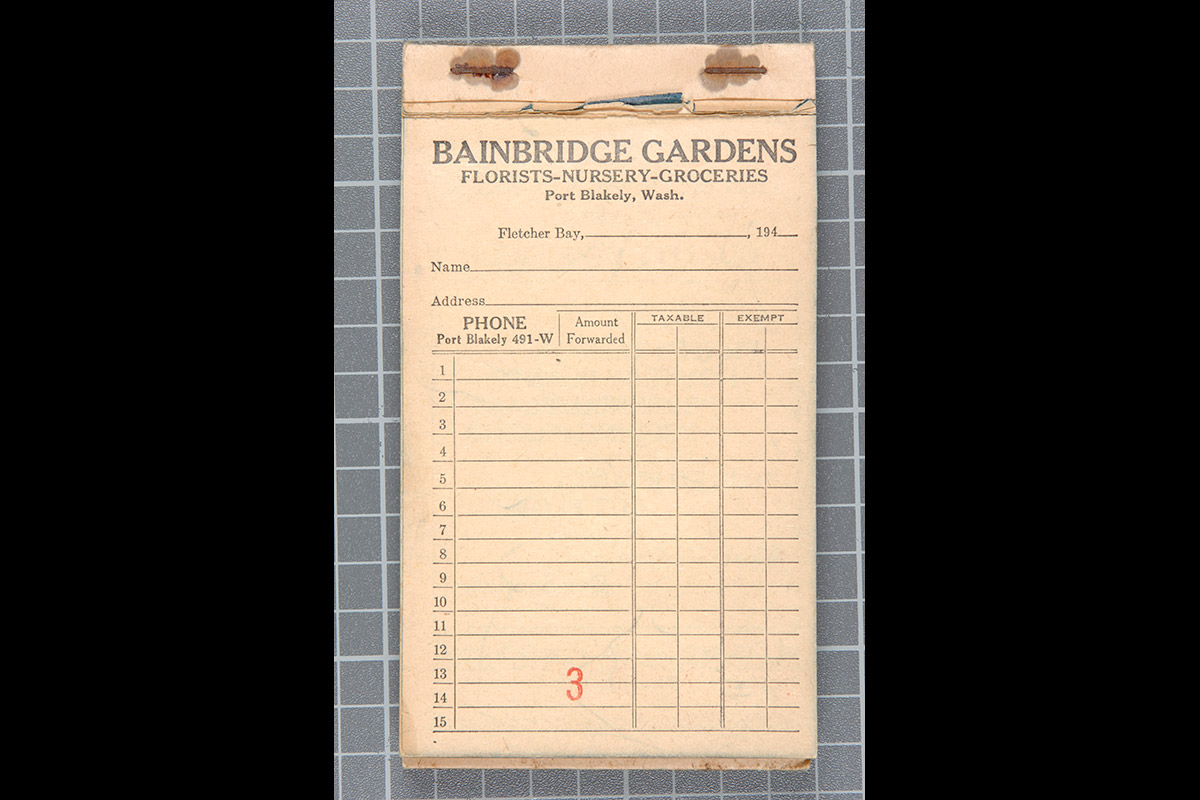

Zenhichi Harui attempted to rebuild Bainbridge Gardens, but he was getting on in age and had little savings. He was never able to get the business back to where it was before the war. Thirty years later, his son Junkoh would finally re-build Bainbridge Gardens at this same location and today it is once again a beautiful and thriving business. Bainbridge Gardens Receipt - blank

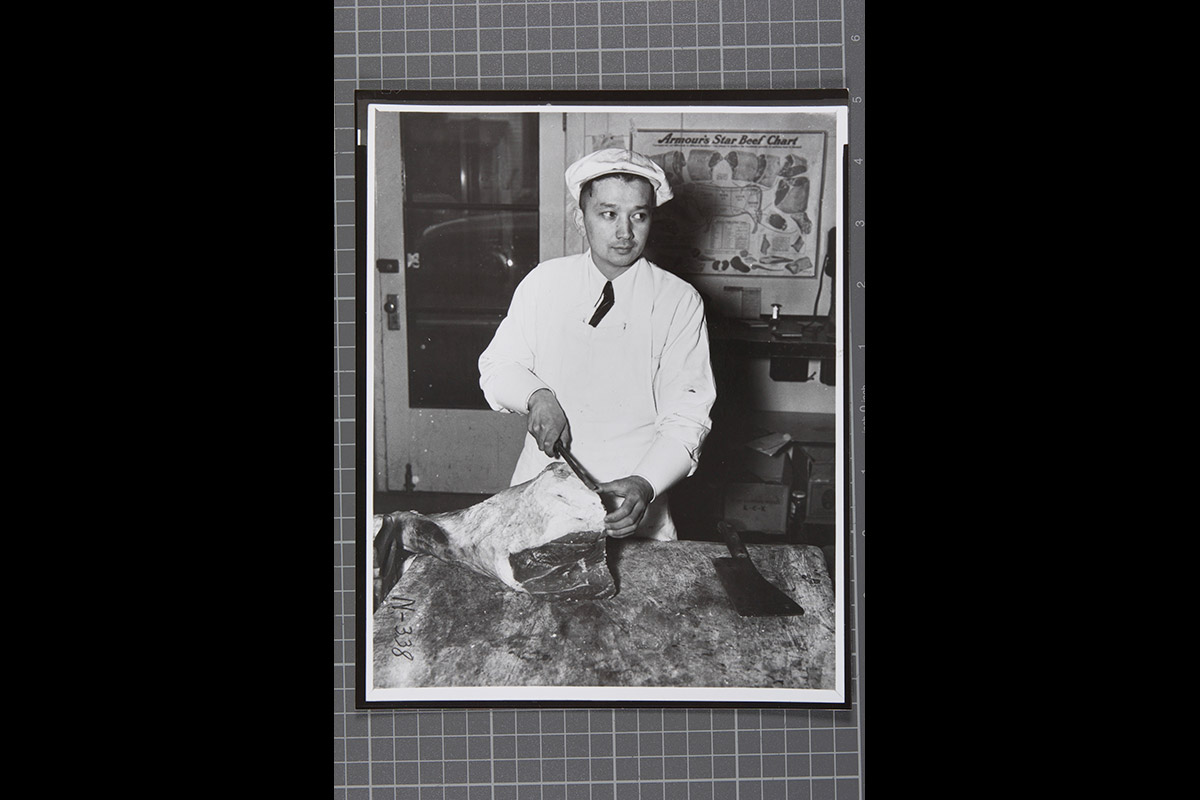

Bainbridge Gardens Receipt - blank What started as a barbershop and laundry in the early 1920s, soon transformed into a grocery store located at the intersection of Winslow Way and the highway.

What started as a barbershop and laundry in the early 1920s, soon transformed into a grocery store located at the intersection of Winslow Way and the highway. The Nakatas sold their interests in this grocery store before they were evacuated. After the war Johnny was eventually able to buy back this market. In 1957 Johnny partnered with his brother Mo and longtime friend Ed Loverich to begin Town and Country Markets. (Credit: Museum of History and Industry. Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection)

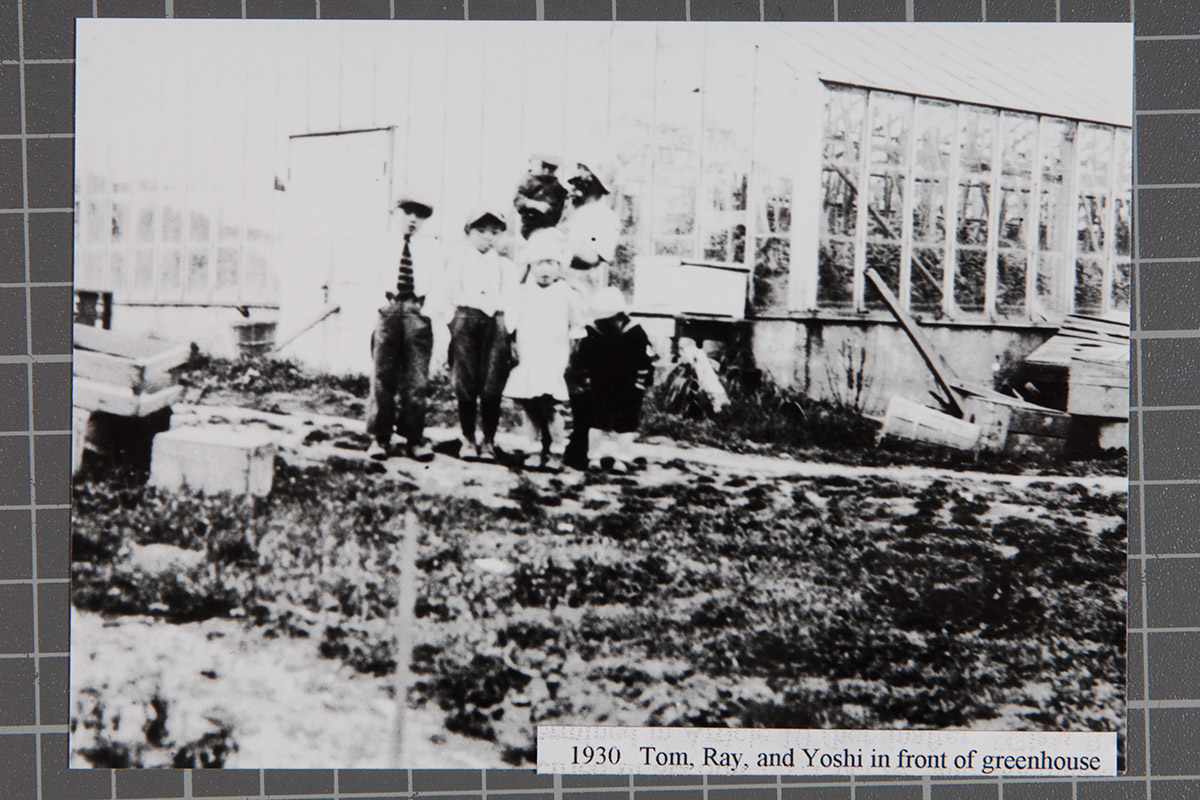

The Nakatas sold their interests in this grocery store before they were evacuated. After the war Johnny was eventually able to buy back this market. In 1957 Johnny partnered with his brother Mo and longtime friend Ed Loverich to begin Town and Country Markets. (Credit: Museum of History and Industry. Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection) The Kitayama's home and greenhouse was located near Lynnwood center.

The Kitayama's home and greenhouse was located near Lynnwood center. Left to right: Tom, Ray, and Yoshi Kitayama. Bainbridge Island, WA

Left to right: Tom, Ray, and Yoshi Kitayama. Bainbridge Island, WA The Katayama greenhouse was located near Wing Point golf course. They also had an orchard.

The Katayama greenhouse was located near Wing Point golf course. They also had an orchard. Furuta's greenhouse located off of Pleasant Beach road.

Furuta's greenhouse located off of Pleasant Beach road. Nagatani farm and greenhouse were on High School Road across from Hayashida home.

Nagatani farm and greenhouse were on High School Road across from Hayashida home. Kiwa Nagatani holding daughter Kiyo. Circa 1921.

Kiwa Nagatani holding daughter Kiyo. Circa 1921.

The following images show some of the young Nikkei families of Bainbridge Island just prior to World War II. They were quite western in their dress and culture. Many of these families, like the Sakais and Hayashidas were becoming comfortable financially when the war broke out. Their farms were at their highest production rate and they had just built new homes. All was put on hold when they were forced to leave.

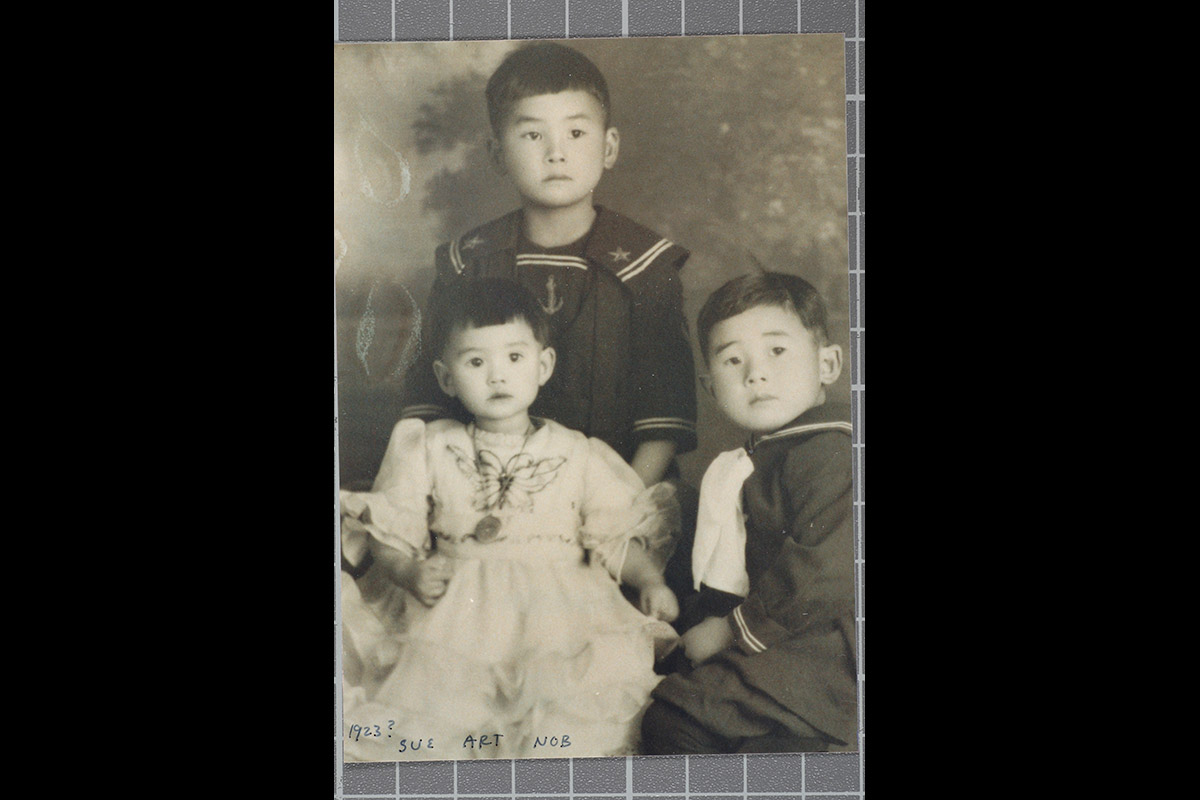

Left to right: Sue, Art, and Nob Koura

Left to right: Sue, Art, and Nob Koura Frank Kitamoto and Shigeko Nishinaka's Wedding Photo. Left to right: Nobuko Nishinaka, unknown, unknown, Shigeko Kitamoto, Frank Kitamoto, Mary Miyauchi, and unknown.

Frank Kitamoto and Shigeko Nishinaka's Wedding Photo. Left to right: Nobuko Nishinaka, unknown, unknown, Shigeko Kitamoto, Frank Kitamoto, Mary Miyauchi, and unknown. Wedding photo. 1932.

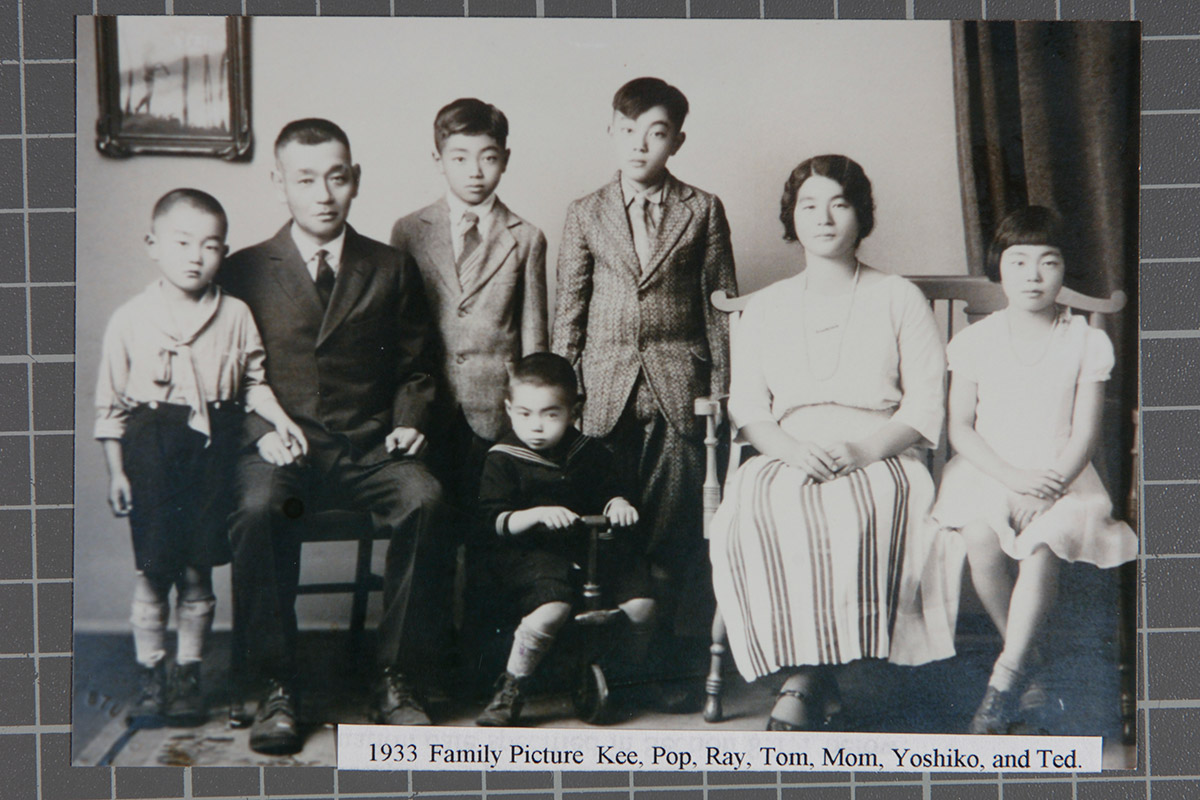

Wedding photo. 1932. Left to right: Kee, Takeshi, Ray, Ted, Tom, Masuko, Yoshiko Kitayama. 1933

Left to right: Kee, Takeshi, Ray, Ted, Tom, Masuko, Yoshiko Kitayama. 1933 In 1925 Reverend Hirakawa and Reverend F. Okazaki began to hand-build the small Winslow Japanese Baptist Church on the corner of property owned by Takeo Sakuma near the intersection of Wyatt and Finch Roads. Rev. Hirakawa would continue to work on this church for the next two years.

In 1925 Reverend Hirakawa and Reverend F. Okazaki began to hand-build the small Winslow Japanese Baptist Church on the corner of property owned by Takeo Sakuma near the intersection of Wyatt and Finch Roads. Rev. Hirakawa would continue to work on this church for the next two years. 1936. Toshio, Sonoji, Yaeko, Nobuko, Taeko, Chiyoko, Yoshiko. The Sakais had just moved into their new home, which had prized amenities such as electricity and indoor plumbing.

1936. Toshio, Sonoji, Yaeko, Nobuko, Taeko, Chiyoko, Yoshiko. The Sakais had just moved into their new home, which had prized amenities such as electricity and indoor plumbing. Left to right: Nobuko, Yasuko, Tomiko, Hisako, Ichiro. 1937. Nobuko and Ichiro Hayashida shared a home with Ichiro’s younger brother, Tsuneichi, and his other brother, Saburo and his young family. Brothers, Ichiro and Saburo, married sisters, Nobuko and Fumiko. Together five adults and seven children under the age of 7 years old lived together under one roof.

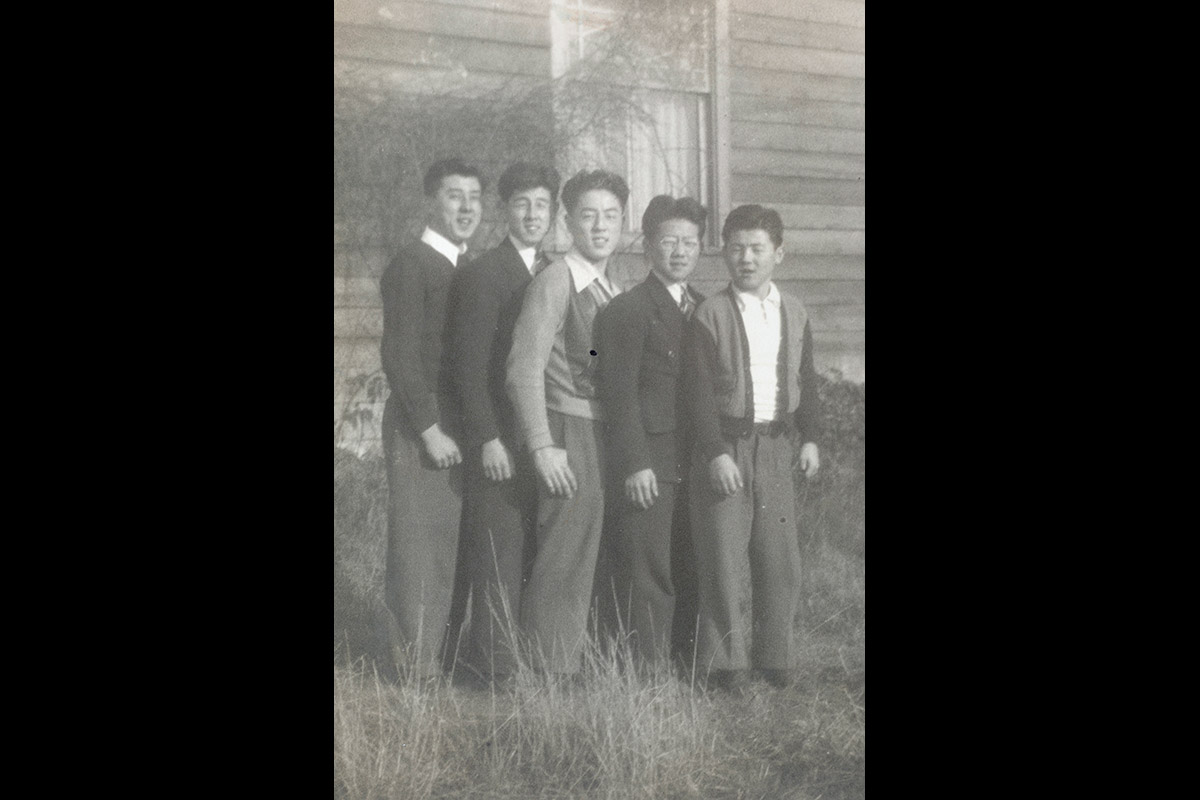

Left to right: Nobuko, Yasuko, Tomiko, Hisako, Ichiro. 1937. Nobuko and Ichiro Hayashida shared a home with Ichiro’s younger brother, Tsuneichi, and his other brother, Saburo and his young family. Brothers, Ichiro and Saburo, married sisters, Nobuko and Fumiko. Together five adults and seven children under the age of 7 years old lived together under one roof. Left to right: Frank, Bob, Harry, Fred, and John

Left to right: Frank, Bob, Harry, Fred, and John Left to right: Frank Koba, Fujiko Koba, Fui Hayashi-Koba, Kichijiro Koba, Bob Koba. Kneeling: John Koba, Harry Koba, Fred Koba

Left to right: Frank Koba, Fujiko Koba, Fui Hayashi-Koba, Kichijiro Koba, Bob Koba. Kneeling: John Koba, Harry Koba, Fred Koba At family farm and home off High School Road. Circa late 1940s.

At family farm and home off High School Road. Circa late 1940s. Left to right: Shizue Yukawa, Toshiko Yukawa, Sumio Yukawa, Junji Yukawa, Taneo Hayashida. Circa 1940.

Left to right: Shizue Yukawa, Toshiko Yukawa, Sumio Yukawa, Junji Yukawa, Taneo Hayashida. Circa 1940. Back: Sono Kino. Front, left to right: Shoji, Setsuko, Reiko - Kino

Back: Sono Kino. Front, left to right: Shoji, Setsuko, Reiko - Kino

Young Filipino men, seeking work on the farms, began to arrive on the Island in the late 1920s. They became the foremen for many of these Japanese farms and soon they too settled down and started families. When the Japanese farmers were forced to leave their land, they turned to their trusted Filipino workers to look after their homes and land while they were away. Due to the presence of people on the land and in the homes, vandalism and destruction was kept to a minimum, which allowed many Nikkei who owned their land to return at the close of the war.

The Katayama farm was located at the corner of Cave Avenue and Winslow Way in downtown Winslow.

The Katayama farm was located at the corner of Cave Avenue and Winslow Way in downtown Winslow. The Sakuma Farm was located off Wyatt road between Finch and Weaver, across the street from where St. Barnabas Church is today. Following the war the Sakumas moved to the Burlington area and resumed strawberry farming.

The Sakuma Farm was located off Wyatt road between Finch and Weaver, across the street from where St. Barnabas Church is today. Following the war the Sakumas moved to the Burlington area and resumed strawberry farming. In 1923 the Winslow Berry Growers Association was formed and they built this cannery, located at the end of Weaver road near Eagle Harbor.

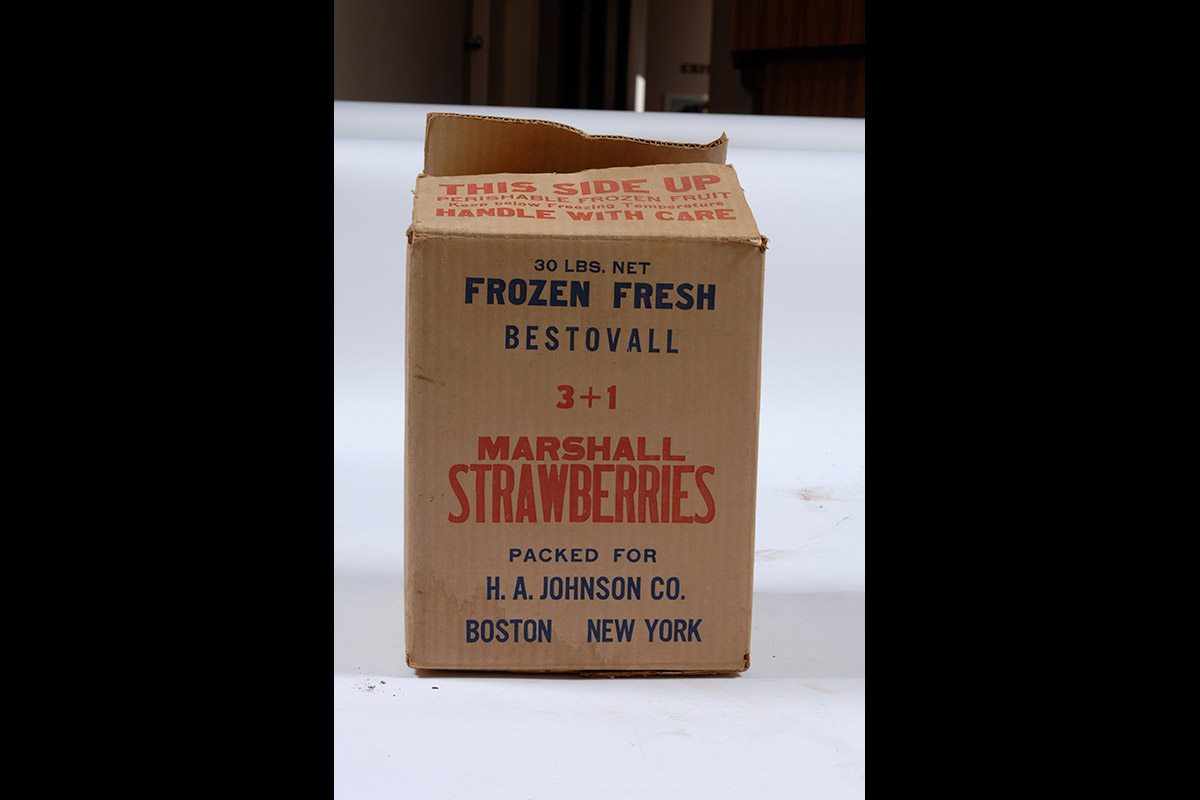

In 1923 the Winslow Berry Growers Association was formed and they built this cannery, located at the end of Weaver road near Eagle Harbor. Otohiko Koura (right) is shown here on his farm with R.D. Bodle who owned a berry canning company based in Seattle. In 1940, Japanese Bainbridge Island farmers and the R.D. Bodle Company sent two million pounds of Marshall berries to market. The Koura strawberry fields were located about where the Bainbridge Island Public Library is today.

Otohiko Koura (right) is shown here on his farm with R.D. Bodle who owned a berry canning company based in Seattle. In 1940, Japanese Bainbridge Island farmers and the R.D. Bodle Company sent two million pounds of Marshall berries to market. The Koura strawberry fields were located about where the Bainbridge Island Public Library is today. Mr. Matsukawa in front of his home. The Matsukawa home was located up the road from the cannery. The cannery's location right off of Eagle Harbor allowed easy transfer to boats that carried the berries to Seattle.

Mr. Matsukawa in front of his home. The Matsukawa home was located up the road from the cannery. The cannery's location right off of Eagle Harbor allowed easy transfer to boats that carried the berries to Seattle. Elaulio and Felix Narte are cousins. In the 1920s they were the foremen for the Nishinaka farm. They stayed in the Kitamoto family home during the war.

Elaulio and Felix Narte are cousins. In the 1920s they were the foremen for the Nishinaka farm. They stayed in the Kitamoto family home during the war. Elaulio and his cousin Felix Narte looked after the Kitamoto property and home during the war. Many Nikkei farmers partnered with their trusted Filipino foremen to harvest the last crop and look after the farms during the war. It was because of these relationships that most of the Islanders who owned land had something to return to after the war.

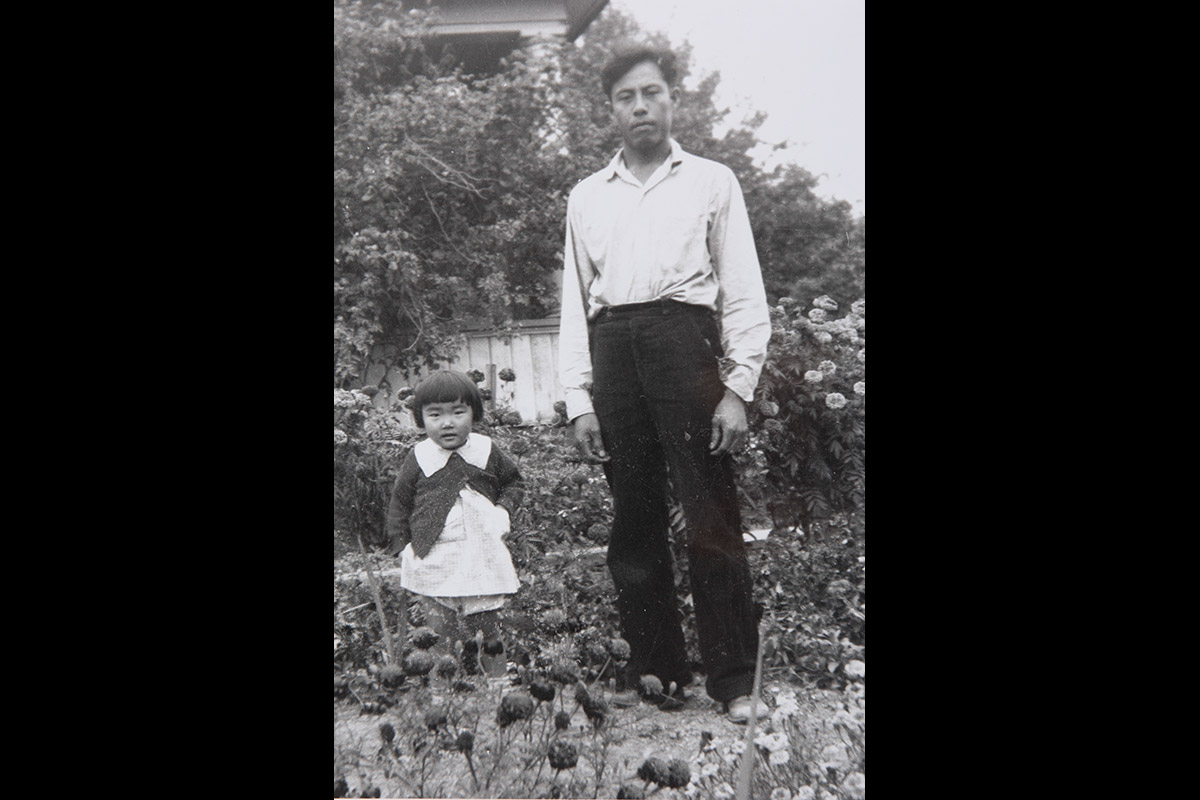

Elaulio and his cousin Felix Narte looked after the Kitamoto property and home during the war. Many Nikkei farmers partnered with their trusted Filipino foremen to harvest the last crop and look after the farms during the war. It was because of these relationships that most of the Islanders who owned land had something to return to after the war. Sonoji Sakai and his daughter Kay look over their farmland, adjacent to their newly built home, just before evacuation. In the 1950s, Mr. and Mrs. Sakai sold part of their land, now where Ordway school stands, to the Bainbridge Island School District at the same price they had paid for it more than a decade earlier. (Credit MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection)

Sonoji Sakai and his daughter Kay look over their farmland, adjacent to their newly built home, just before evacuation. In the 1950s, Mr. and Mrs. Sakai sold part of their land, now where Ordway school stands, to the Bainbridge Island School District at the same price they had paid for it more than a decade earlier. (Credit MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection) Japanese American farmers grew the Marshall variety strawberries, known for their superb taste, on Bainbridge Island both before and after WWII.

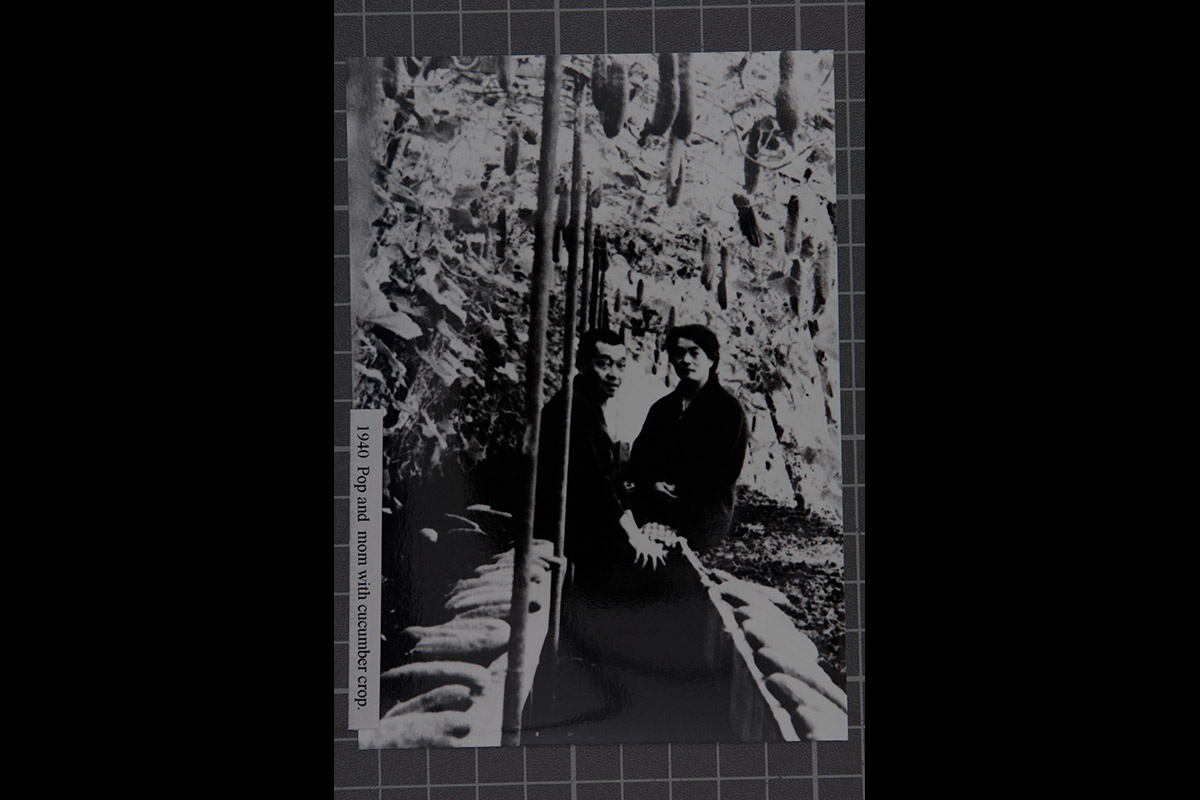

Japanese American farmers grew the Marshall variety strawberries, known for their superb taste, on Bainbridge Island both before and after WWII. Japanese farmers on Bainbridge Island also grew other fruits and vegetables, such as these cucumbers. Fresh produce was brought directly to market and thus called “truck-farming.”

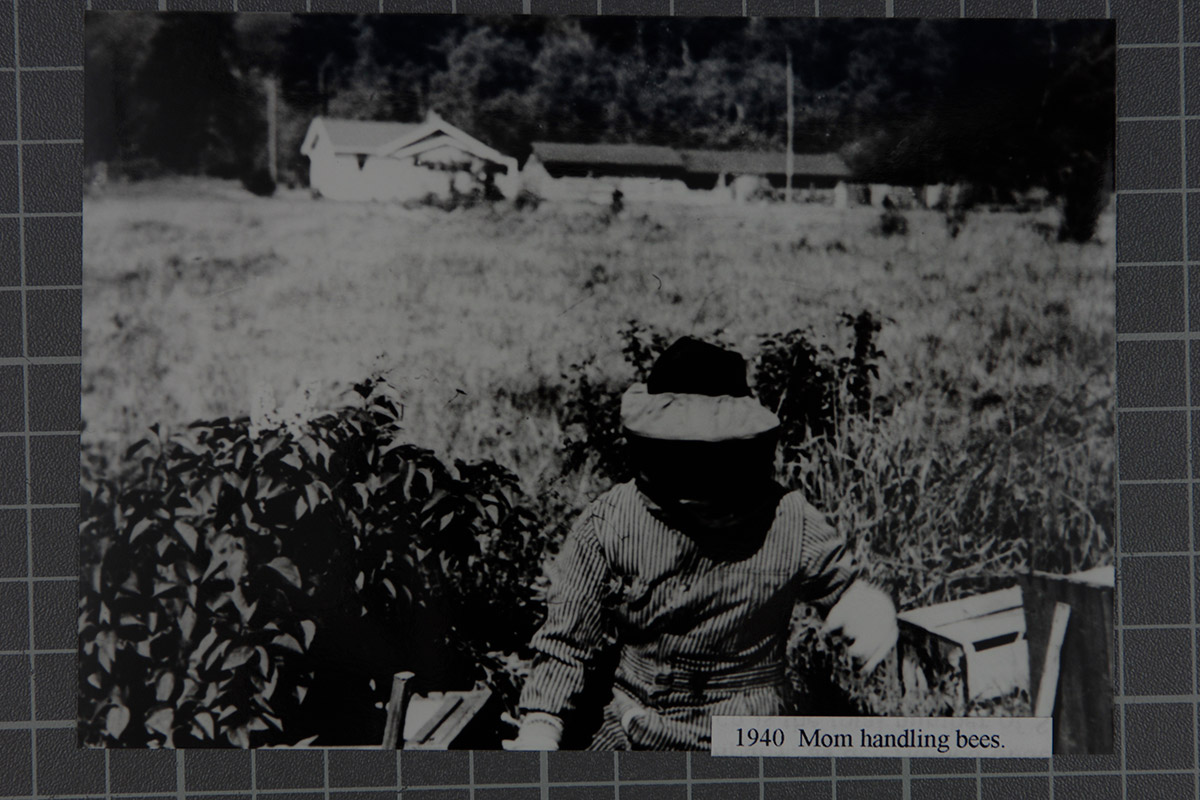

Japanese farmers on Bainbridge Island also grew other fruits and vegetables, such as these cucumbers. Fresh produce was brought directly to market and thus called “truck-farming.” Though strawberries were the principal crop on the Island, all farms were diversified and had other ventures such as the honey being harvested in this photo.

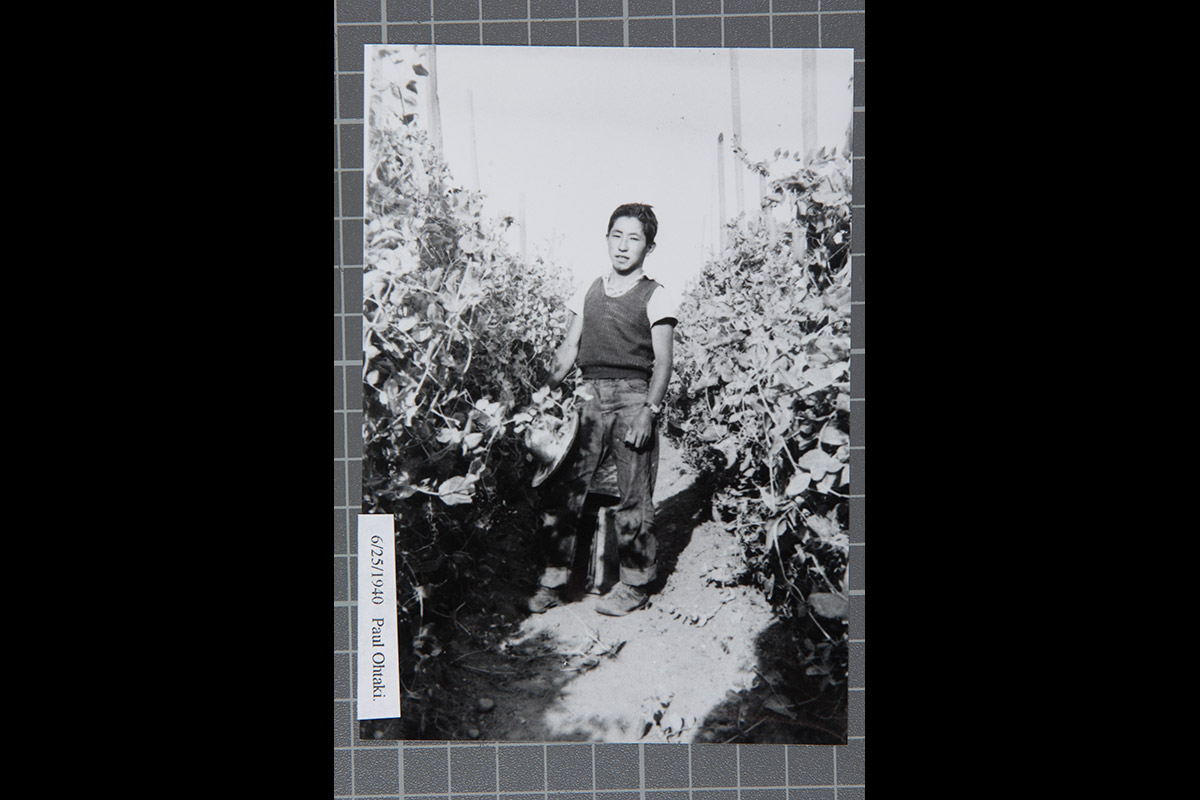

Though strawberries were the principal crop on the Island, all farms were diversified and had other ventures such as the honey being harvested in this photo. The young Nisei, or second generation Japanese Americans, on Bainbridge Island did not have much free time. Those who were from farming families spent weekends and time after school in the fields. Here, Paul, age 15, is picking peas.

The young Nisei, or second generation Japanese Americans, on Bainbridge Island did not have much free time. Those who were from farming families spent weekends and time after school in the fields. Here, Paul, age 15, is picking peas.

Winslow School. 1924.

Winslow School. 1924. Lincoln School 1927-1928

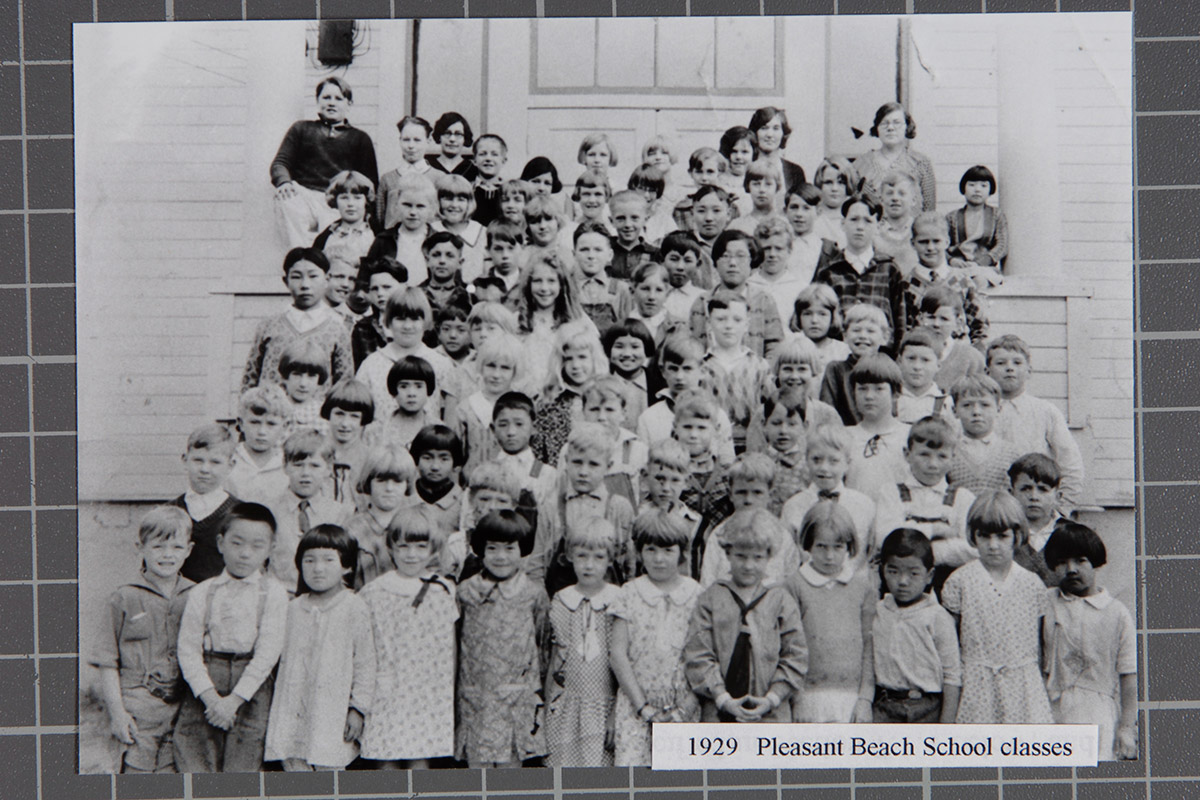

Lincoln School 1927-1928 1929

1929 Teacher and Principal at Pleasant Beach School. Port Blakely, WA. 1938.

Teacher and Principal at Pleasant Beach School. Port Blakely, WA. 1938. Left to right. Front: Michiko Amatatsu, -, Doris Hardy, -, -, Rose Johnson, Fusako Matsushita, -, - 2nd row: Leslie Pousard, Ellen Lund, -, Jim Henshaw, Robert Koba, Peter Ohtaki, - Sakae Chihara. 3rd row: Alfred Larsen, -, Jack Freeman, Janet Cunningham, Freeman, Masa Omoto, Shig Moritani, Nob Oyama.

Left to right. Front: Michiko Amatatsu, -, Doris Hardy, -, -, Rose Johnson, Fusako Matsushita, -, - 2nd row: Leslie Pousard, Ellen Lund, -, Jim Henshaw, Robert Koba, Peter Ohtaki, - Sakae Chihara. 3rd row: Alfred Larsen, -, Jack Freeman, Janet Cunningham, Freeman, Masa Omoto, Shig Moritani, Nob Oyama. Circa 1928

Circa 1928 Circa 1927

Circa 1927 Bainbridge Island High School. The class is modeling the clothes they sewed for a class project.

Bainbridge Island High School. The class is modeling the clothes they sewed for a class project. Bainbridge Island High School - 1938

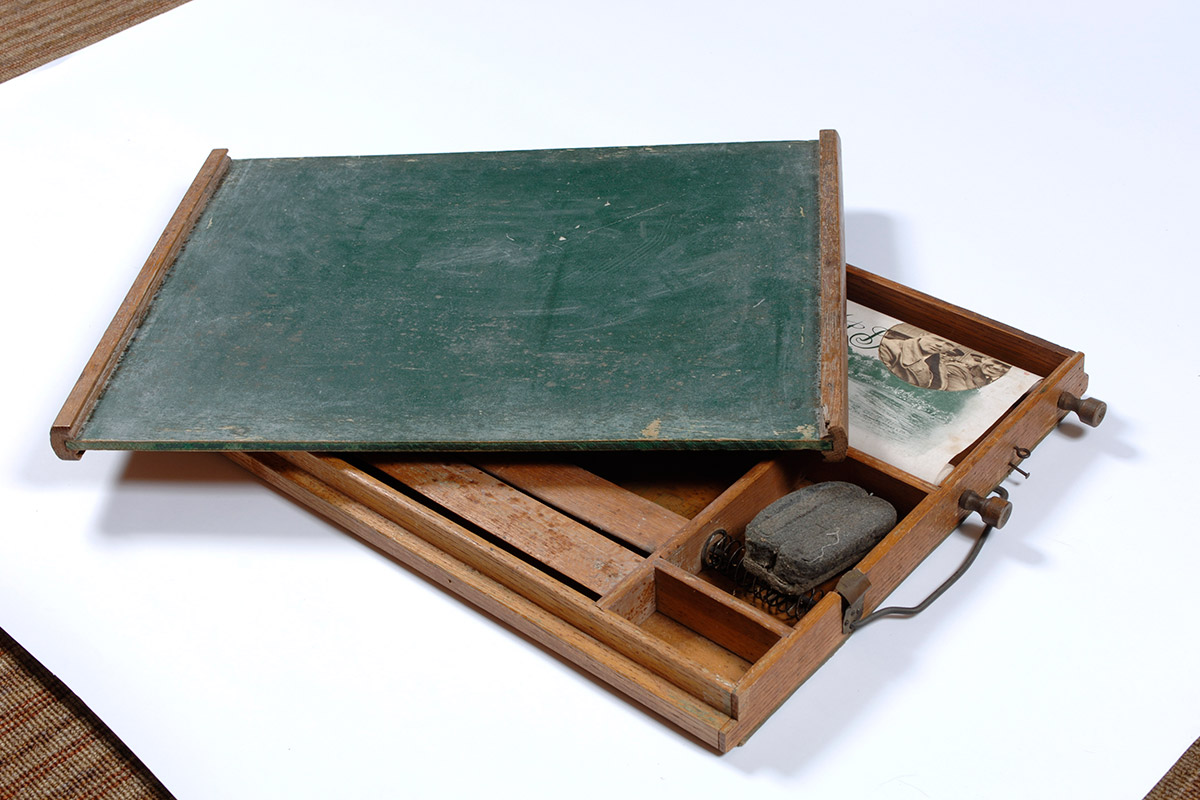

Bainbridge Island High School - 1938 Home Study Student Work Desk - Owned by the Moritani family.

Home Study Student Work Desk - Owned by the Moritani family. Winslow High School Letter - Earned by one of the Moritani brothers. Circa 1930s

Winslow High School Letter - Earned by one of the Moritani brothers. Circa 1930s Bainbridge Island High Sports Uniform Shorts - Owned by one of the Moritani brothers. Circa 1940

Bainbridge Island High Sports Uniform Shorts - Owned by one of the Moritani brothers. Circa 1940 Insignia for Winslow High School Letterman's Jacket

Insignia for Winslow High School Letterman's Jacket Bainbridge Island High School Letterman's Jacket - Owned by one of the Moritani brothers. Circa 1940

Bainbridge Island High School Letterman's Jacket - Owned by one of the Moritani brothers. Circa 1940 Knee Pad owned by one of the Moritani brothers. Circa 1940.

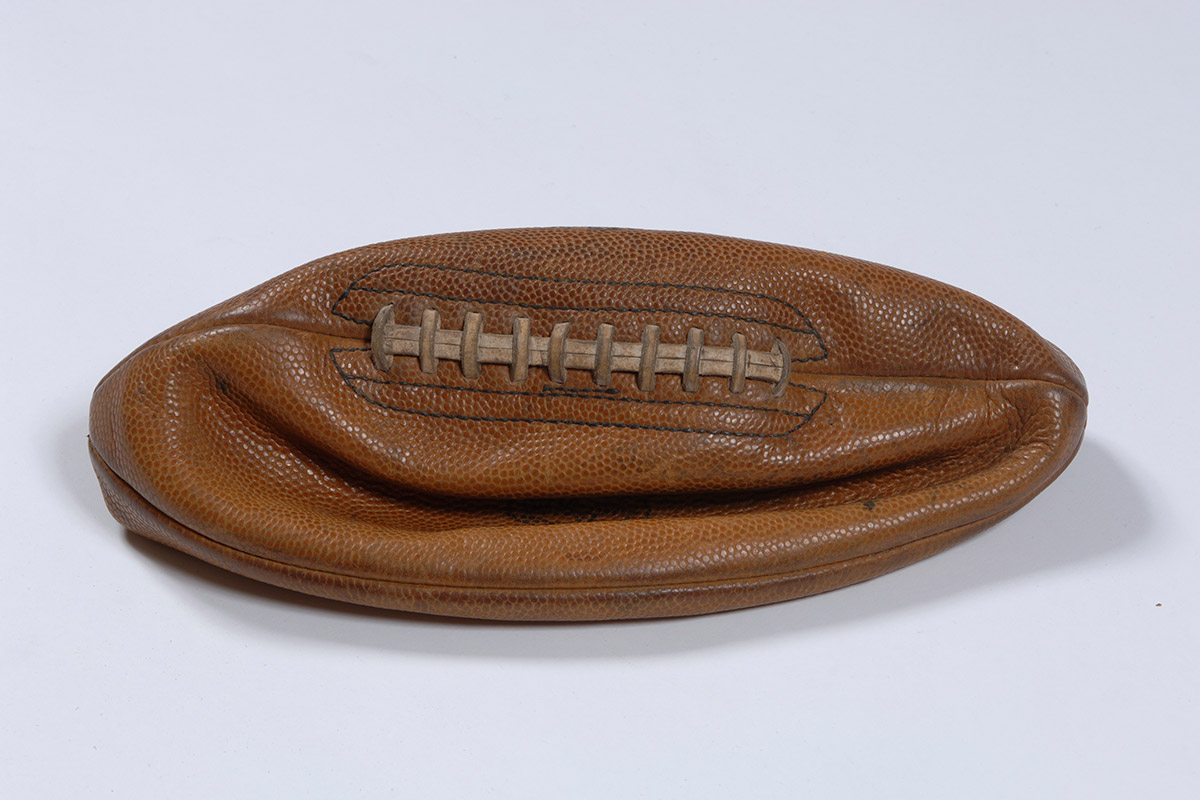

Knee Pad owned by one of the Moritani brothers. Circa 1940. Football Circa 1940

Football Circa 1940 Ichiro Nagatani in Baseball Uniform

Ichiro Nagatani in Baseball Uniform This was Kiyo Nagatani's baseball letter.

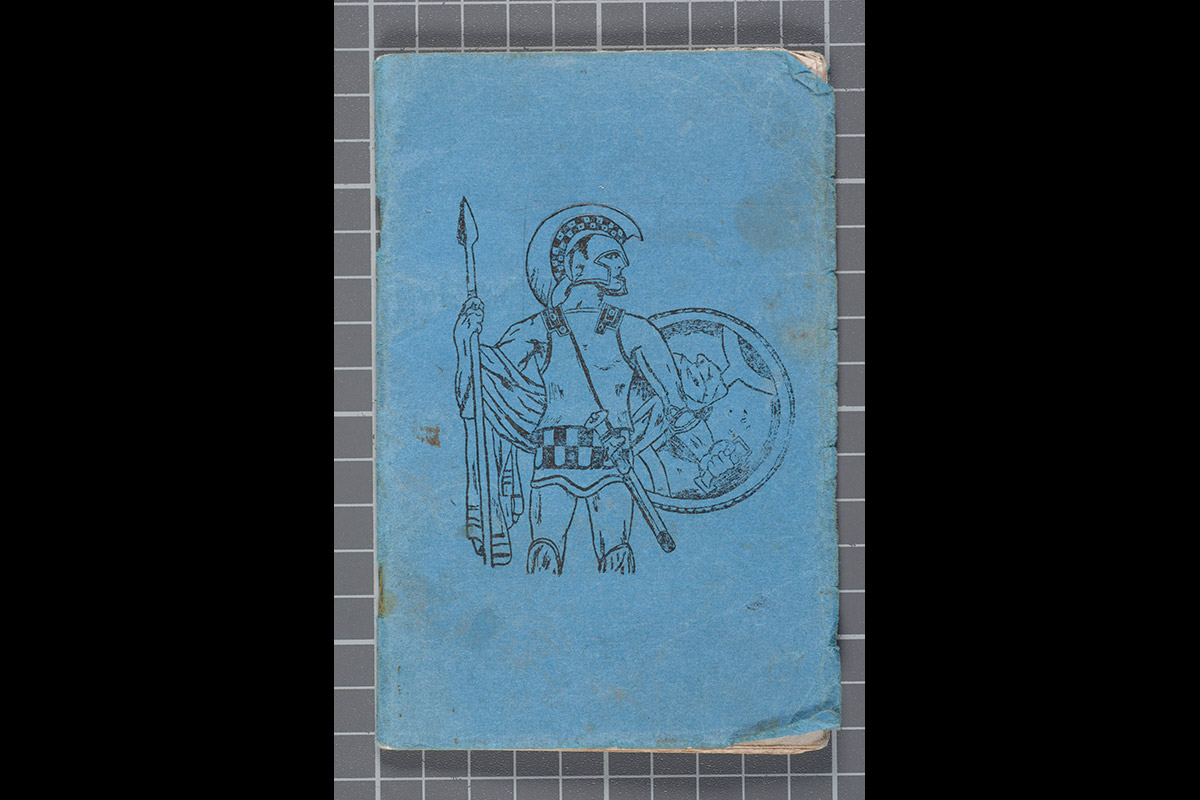

This was Kiyo Nagatani's baseball letter. Spartans, BIHS yearbook, 1931

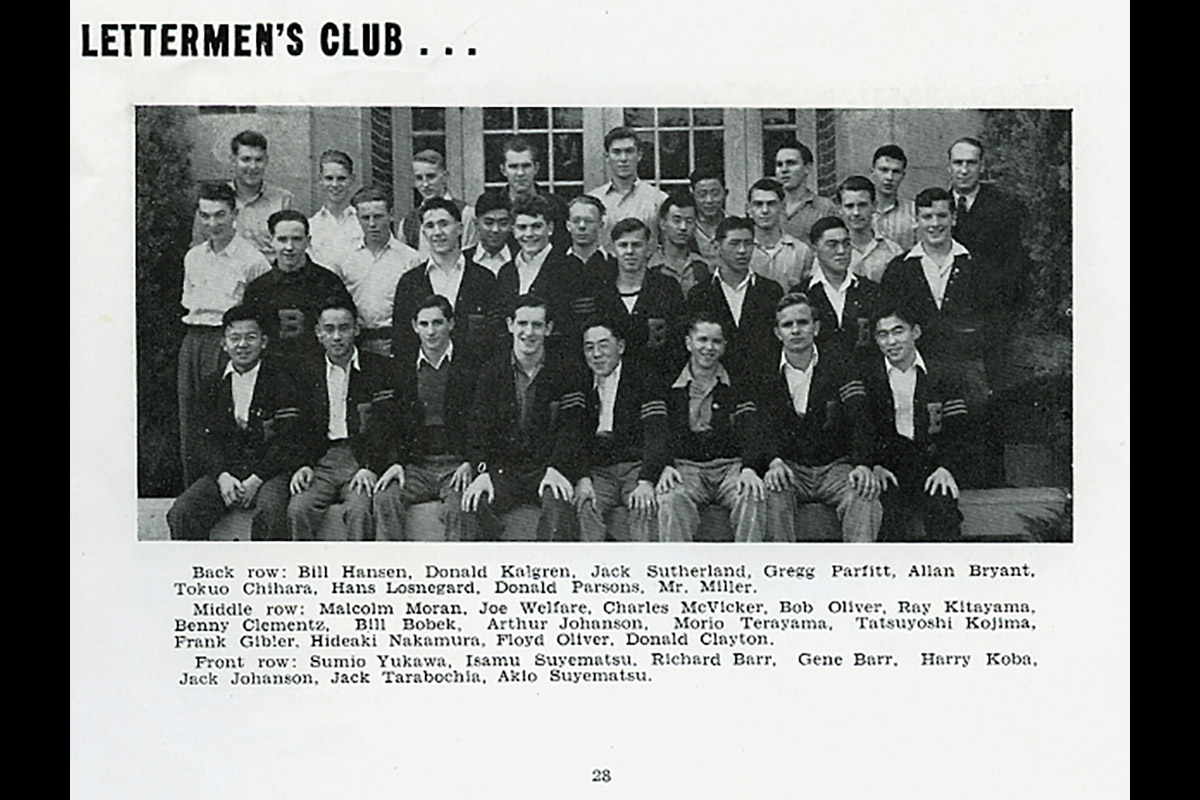

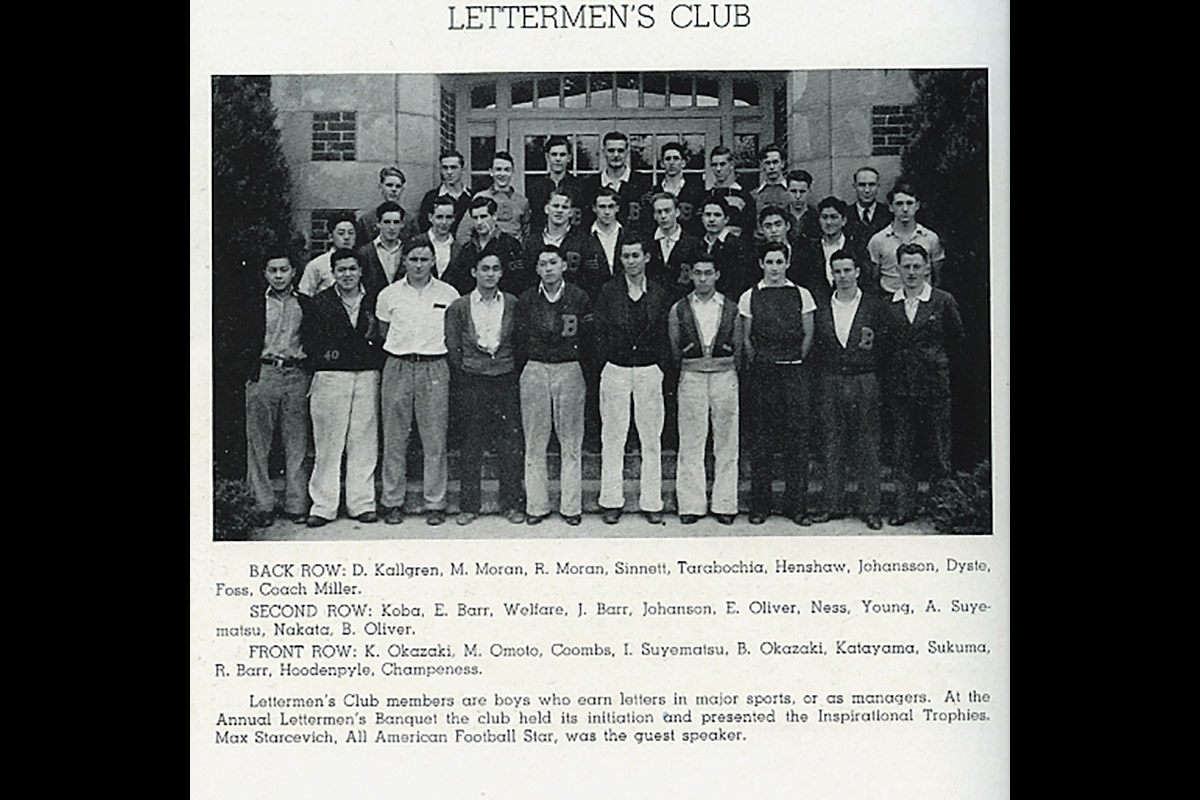

Spartans, BIHS yearbook, 1931 1942 BHS Lettermen's Club - Bainbridge Island Historical Society

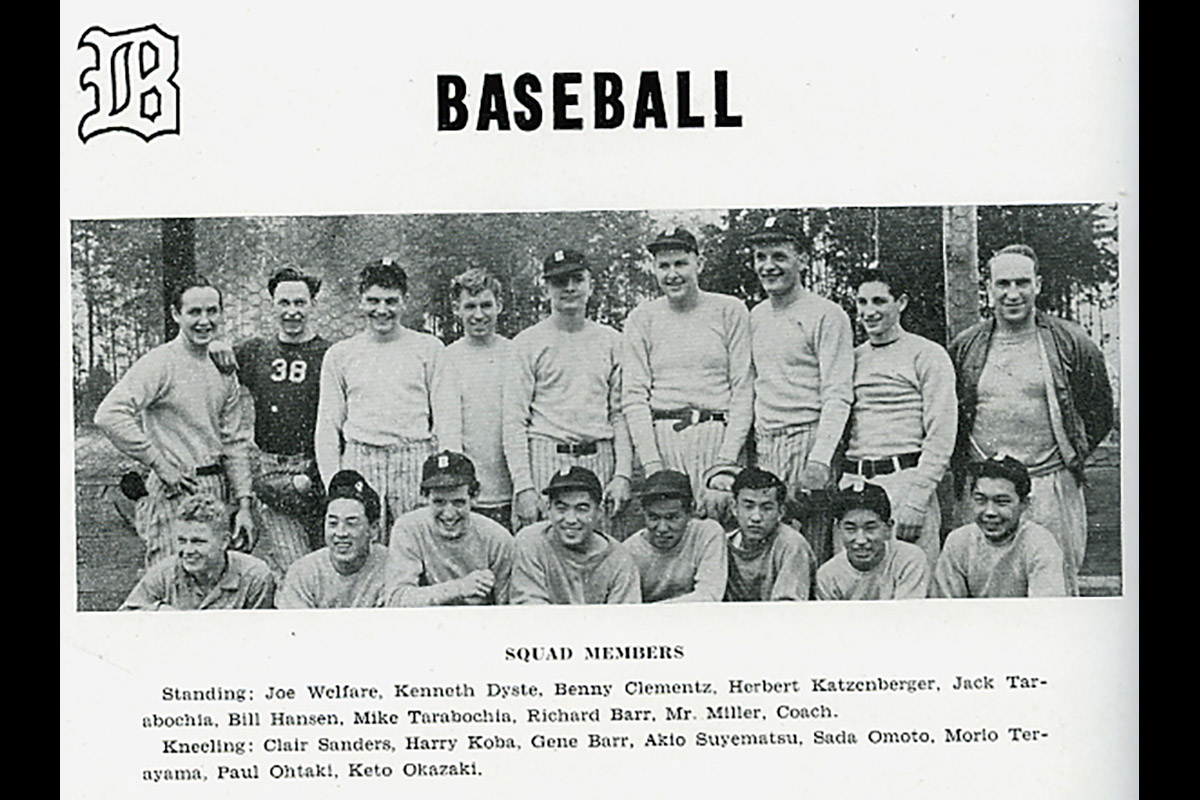

1942 BHS Lettermen's Club - Bainbridge Island Historical Society 1941 Spartan Baseball Team - Bainbridge Island Historical Society

1941 Spartan Baseball Team - Bainbridge Island Historical Society 1940 BHS Lettermen's Club - Bainbridge Island Historical Society

1940 BHS Lettermen's Club - Bainbridge Island Historical Society

Summer picnics have been a long tradition for the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community. Before the war families lived far apart on this rural island and picnics provided a chance for them to get together, share good food, and relax.

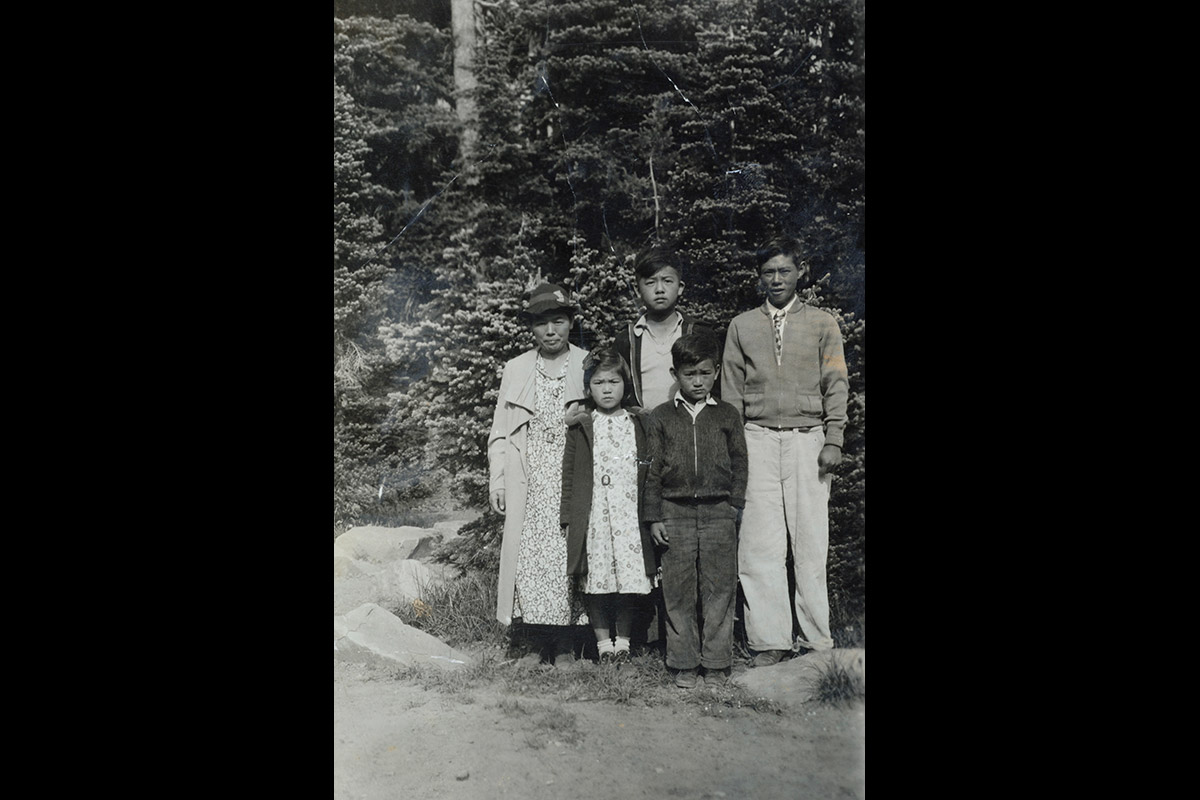

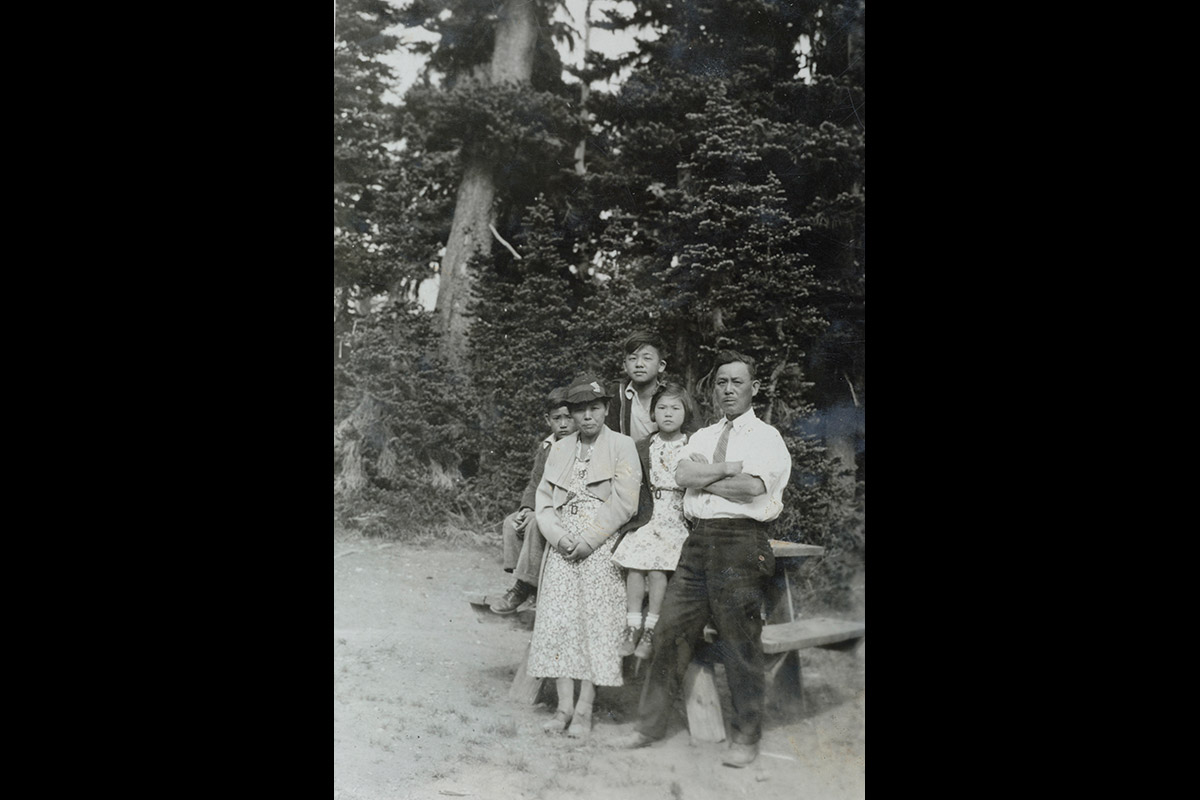

Summer picnics have been a long tradition for the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community. Before the war families lived far apart on this rural island and picnics provided a chance for them to get together, share good food, and relax. These three families were able to move outside of Military Area No. 1 by arranging to farm east of the Cascade Mountains in Moses Lake, Washington. It took quick planning and their savings to make this happen in the short three-week window allowed by the US government. They remained there throughout the war. Here they are gathered for a family picnic circa 1935-40. (Credit: Bainbridge Island Historical Society, Junkoh Harui Collection)

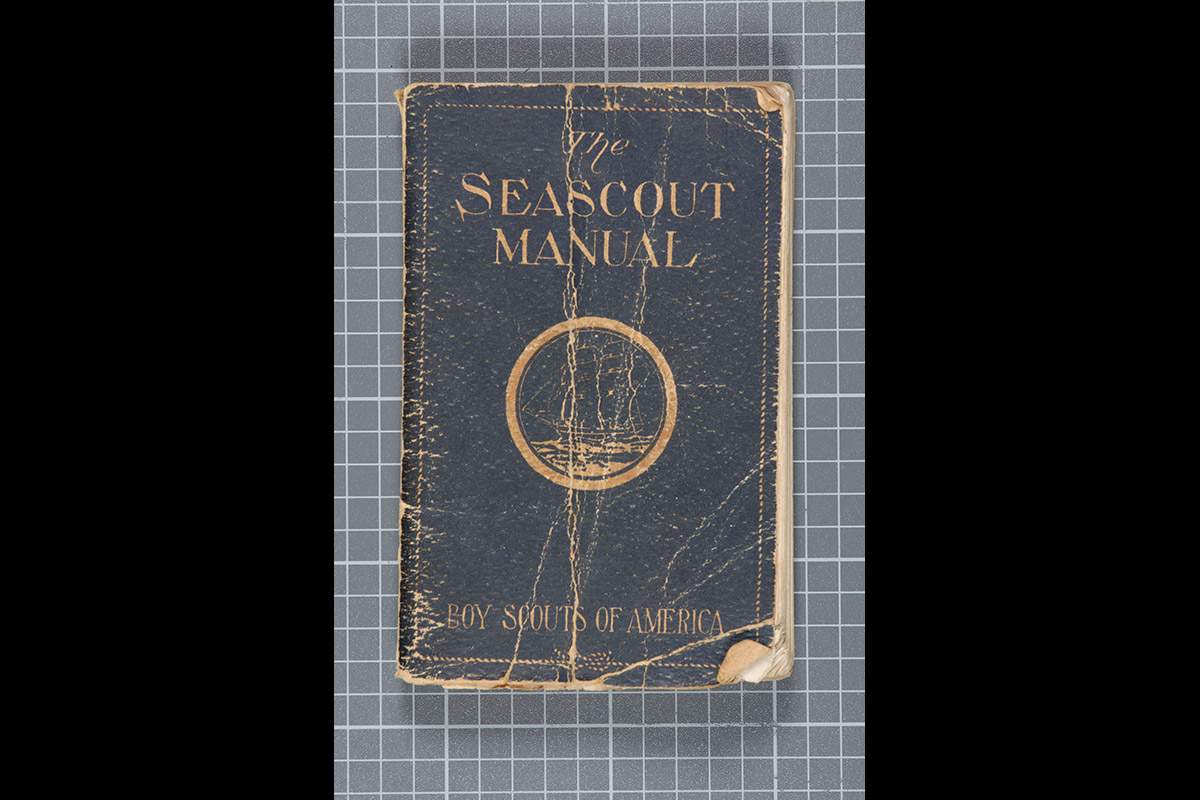

These three families were able to move outside of Military Area No. 1 by arranging to farm east of the Cascade Mountains in Moses Lake, Washington. It took quick planning and their savings to make this happen in the short three-week window allowed by the US government. They remained there throughout the war. Here they are gathered for a family picnic circa 1935-40. (Credit: Bainbridge Island Historical Society, Junkoh Harui Collection) All of the Moritani brothers took part in Sea Scouts. Outside of sports, Scouts was a popular past time for many young Japanese Americans on Bainbridge Island.

All of the Moritani brothers took part in Sea Scouts. Outside of sports, Scouts was a popular past time for many young Japanese Americans on Bainbridge Island. Sea Scouts is a special department under the Boy Scouts of America organization, designed for kids ages 14 to 18. It is still in existence today.

Sea Scouts is a special department under the Boy Scouts of America organization, designed for kids ages 14 to 18. It is still in existence today. When Sea Scouts became organized in the 1920s, members were required to be boys of at least 15 years of age. Many who graduated from Boy Scouts moved on to Sea Scouts. Members gained leadership skills while learning about boat management and seamanship.

When Sea Scouts became organized in the 1920s, members were required to be boys of at least 15 years of age. Many who graduated from Boy Scouts moved on to Sea Scouts. Members gained leadership skills while learning about boat management and seamanship. Many Island families were Buddhist and took part in temple activities. These young girls have dressed up in traditional Japanese kimono, hair-dress, and makeup for a dance festival.

Many Island families were Buddhist and took part in temple activities. These young girls have dressed up in traditional Japanese kimono, hair-dress, and makeup for a dance festival. This team played throughout the Kitsap Peninsula and in Seattle. Left to right. Back: ? Okazaki, Ichiro Nagatani, Taketo Omoto (dark shirt), Nob Moritani, Seiji Okazaki, John Nakata? Front: Kiyo Nagatani,? Okazaki,? (looking sideways), George Oyama, Sam Nakao, ? Okazaki.

This team played throughout the Kitsap Peninsula and in Seattle. Left to right. Back: ? Okazaki, Ichiro Nagatani, Taketo Omoto (dark shirt), Nob Moritani, Seiji Okazaki, John Nakata? Front: Kiyo Nagatani,? Okazaki,? (looking sideways), George Oyama, Sam Nakao, ? Okazaki. Left to right. Back: Art Koura, Ichiro Nagatani; Middle: Mamoru Shibukawa, Akira Shibukawa, Nob Koura; Front: Hank Ogawa, Kiyo Nagatani, Akira Sakuma, Tike Nishimori. Bainbridge Island, WA.

Left to right. Back: Art Koura, Ichiro Nagatani; Middle: Mamoru Shibukawa, Akira Shibukawa, Nob Koura; Front: Hank Ogawa, Kiyo Nagatani, Akira Sakuma, Tike Nishimori. Bainbridge Island, WA. Fumiko Hayashida, Mamoru Hayashida, and Hideko Kitamoto. 1939. Bainbridge Island, WA.

Fumiko Hayashida, Mamoru Hayashida, and Hideko Kitamoto. 1939. Bainbridge Island, WA. Judo and other Japanese community social activities took place in the Japanese Hall.

Judo and other Japanese community social activities took place in the Japanese Hall. From left to right: Yuriko Kitamoto, Hideko Kitamoto, Shigeko Kitamoto. Much of what the Japanese families ate was gathered from the beach or from their own farms.

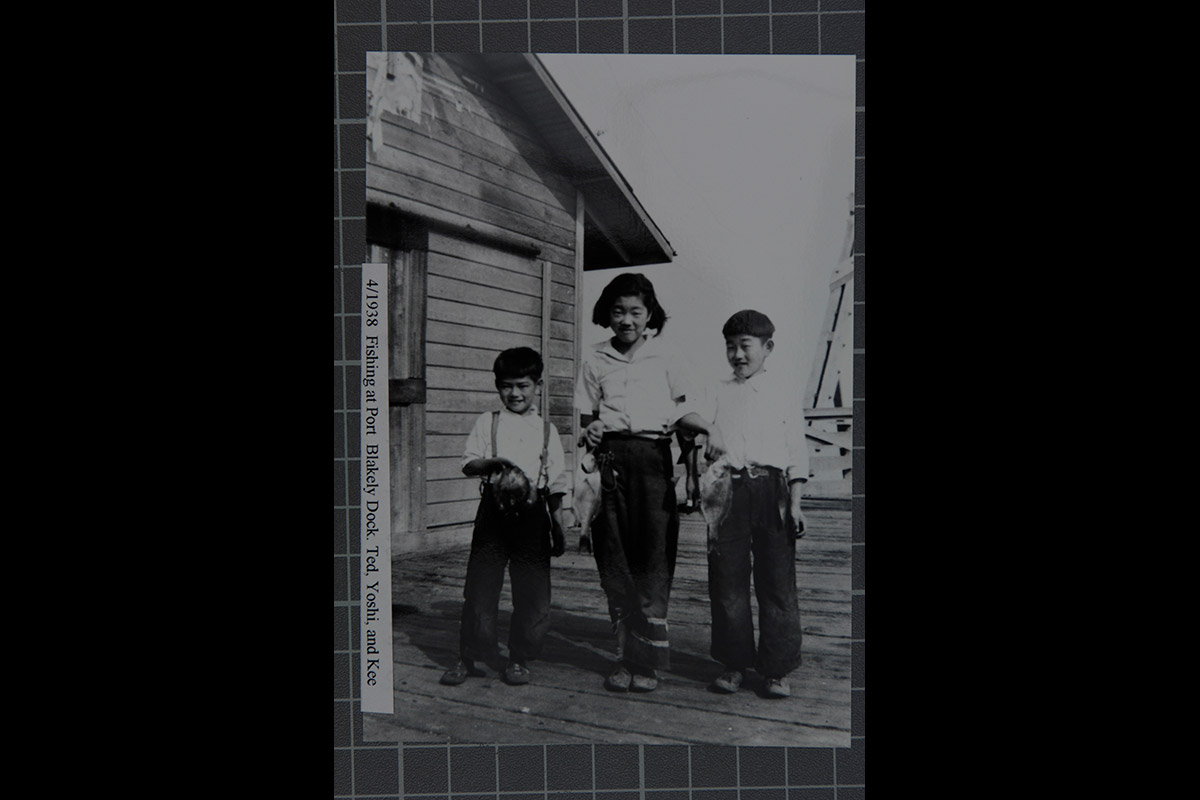

From left to right: Yuriko Kitamoto, Hideko Kitamoto, Shigeko Kitamoto. Much of what the Japanese families ate was gathered from the beach or from their own farms. April 1938. Left to right: Ted, Yoshi, and Kee - Kitayama.

April 1938. Left to right: Ted, Yoshi, and Kee - Kitayama. Left to right: Shigeko Kitamoto, Tomiko Hayashida, Yuriko Kitamoto, Fumiko Hayashida, Hideko Kitamoto, Grandma Tomie Nishinaka, Hiroshi Hayashida (baby), Yasuko Hayashida (in lap), Nobuko Hayashida, Hisako Hayashida, Ichiro Hayashida. At Kitamoto family home on Bainbridge Island, WA.

Left to right: Shigeko Kitamoto, Tomiko Hayashida, Yuriko Kitamoto, Fumiko Hayashida, Hideko Kitamoto, Grandma Tomie Nishinaka, Hiroshi Hayashida (baby), Yasuko Hayashida (in lap), Nobuko Hayashida, Hisako Hayashida, Ichiro Hayashida. At Kitamoto family home on Bainbridge Island, WA. Frank Kitamoto and Shigeko Nishinaka's Wedding Photo. Left to right: Nobuko Nishinaka, unknown, unknown, Shigeko Kitamoto, Frank Kitamoto, Mary Miyauchi, and unknown.

Frank Kitamoto and Shigeko Nishinaka's Wedding Photo. Left to right: Nobuko Nishinaka, unknown, unknown, Shigeko Kitamoto, Frank Kitamoto, Mary Miyauchi, and unknown. Extended families were close knit and often depended on each other to help run the farms, look after the children, and provide social outlets during the little free time they had.

Extended families were close knit and often depended on each other to help run the farms, look after the children, and provide social outlets during the little free time they had. Left to right: Shizue Yukawa, Toshiko Yukawa, Sumio Yukawa, Junji Yukawa, Taneo Hayashida. Circa 1940.

Left to right: Shizue Yukawa, Toshiko Yukawa, Sumio Yukawa, Junji Yukawa, Taneo Hayashida. Circa 1940. In the background is Fletcher’s Bay where many Japanese fished and gathered seaweed and clams.

In the background is Fletcher’s Bay where many Japanese fished and gathered seaweed and clams. Hideko Kitamoto is sitting in her family's back yard with a Japanese paper umbrella and two dogs. Farming life was idyllic for the very young children. When they became school age they were required to work in the fields and take on household chores.

Hideko Kitamoto is sitting in her family's back yard with a Japanese paper umbrella and two dogs. Farming life was idyllic for the very young children. When they became school age they were required to work in the fields and take on household chores. Family trips to the mountains, such as in this photo, were popular weekend outings. Left to right: Junji, Shizue, Sumio, Toshiko, Eizo Yukawa. Circa 1940.

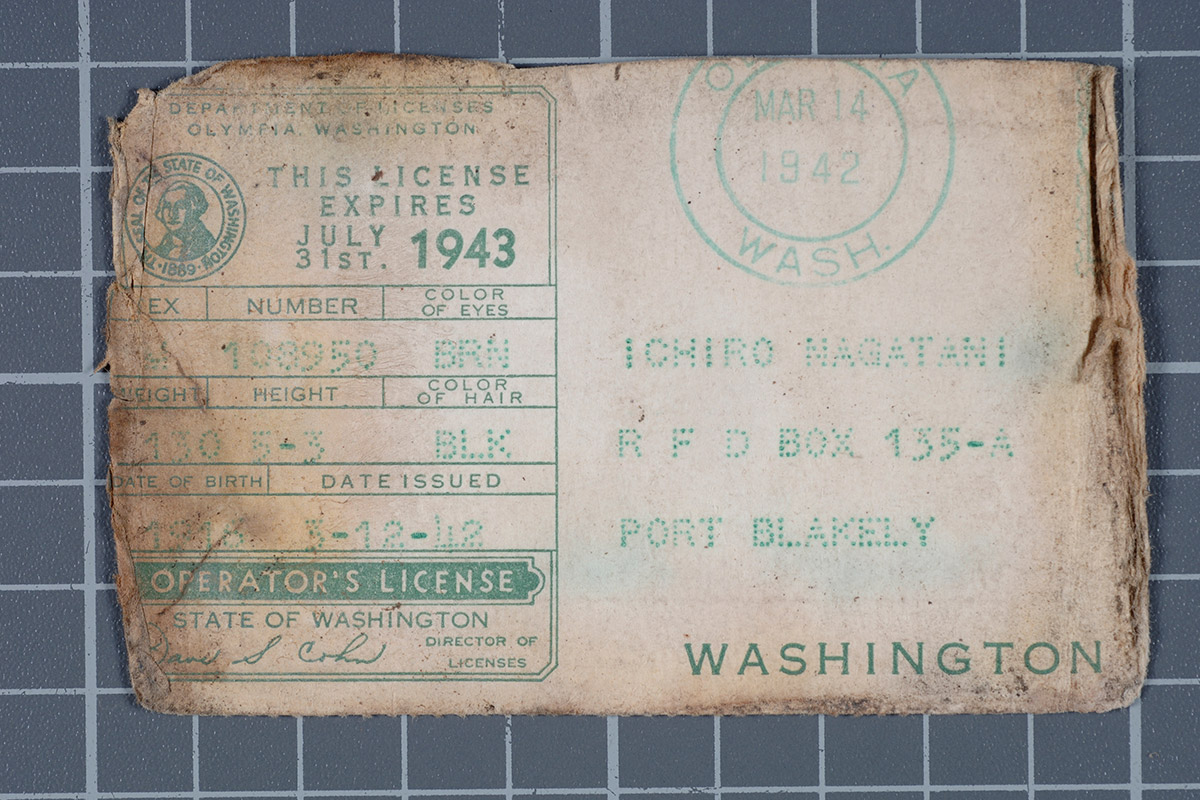

Family trips to the mountains, such as in this photo, were popular weekend outings. Left to right: Junji, Shizue, Sumio, Toshiko, Eizo Yukawa. Circa 1940. Drivers License - Ichiro Nagatani - Expired Jul 31, 1943.

Drivers License - Ichiro Nagatani - Expired Jul 31, 1943. Left to right: Ichiro Hayashida, Shigeko (Nakata) Kawamoto, Fumiko (Nishinaka) Hayashida, Yoshie (Nakata) Iwasa

Left to right: Ichiro Hayashida, Shigeko (Nakata) Kawamoto, Fumiko (Nishinaka) Hayashida, Yoshie (Nakata) Iwasa Back of Drivers License - 1943

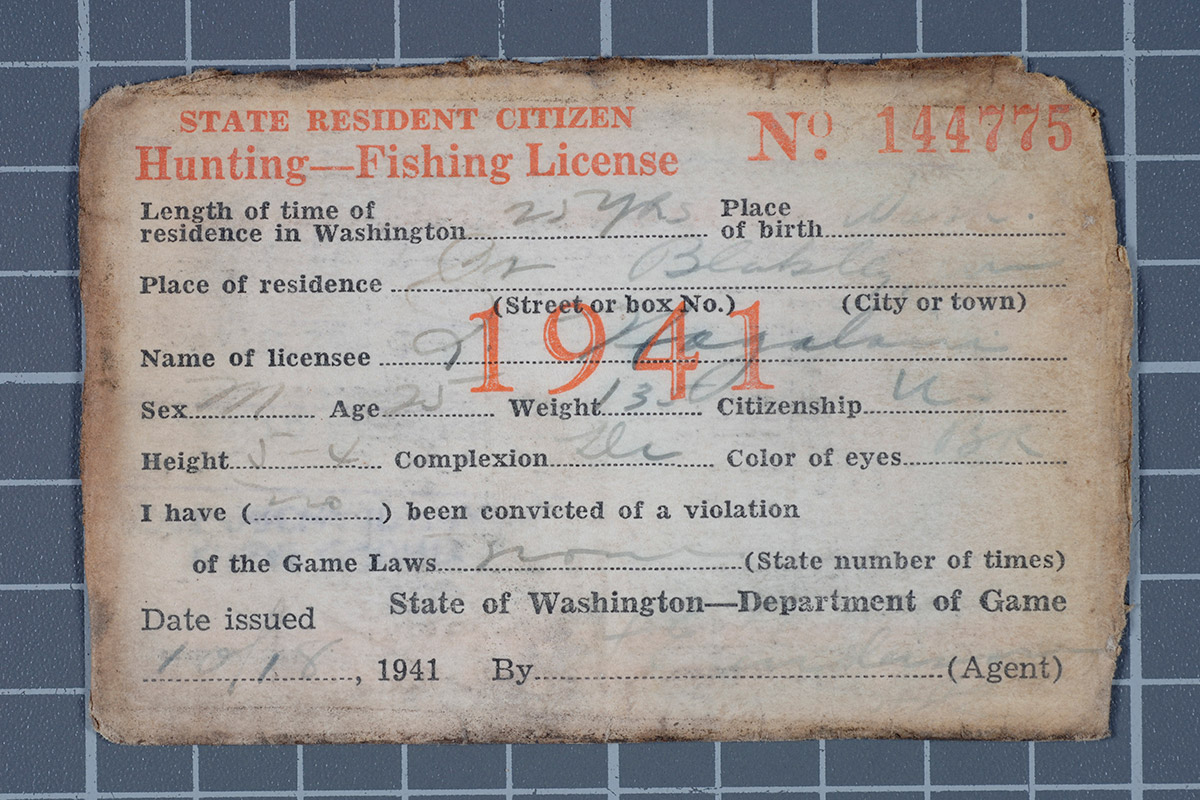

Back of Drivers License - 1943 The U.S. Government confiscated firearms used by the Island’s Nisei for hunting.

The U.S. Government confiscated firearms used by the Island’s Nisei for hunting. George sports his Bainbridge High School letterman’s sweater on an outing to the beach. Between attending school, Japanese school on weekends, church, and farm work, the teenagers on the Island who were from farming families did not get much free time.

George sports his Bainbridge High School letterman’s sweater on an outing to the beach. Between attending school, Japanese school on weekends, church, and farm work, the teenagers on the Island who were from farming families did not get much free time. Left to right: Shigeko Kitamoto and Fujio Arima at Jefferson Park in Seattle. August 4, 1929.

Left to right: Shigeko Kitamoto and Fujio Arima at Jefferson Park in Seattle. August 4, 1929. On display at Sakai Intermediate School. Bainbridge Island, WA. Photographed by Fenwick Publishing 2007.

On display at Sakai Intermediate School. Bainbridge Island, WA. Photographed by Fenwick Publishing 2007.

Oral History

- Friends, Class '41, Japanese school - Jerry Nakata (OH0002)

- Life on the farm, picnics, Japanese films - Eiko Shibayama (OH0031)

- Japanese Hall, school, farming, Caucasian friends - Yae Yoshihara (OH0032)

- Living off the land - Hisa Matsudaira (OH0047)

- Reverend Emery Andrews and his trips to BI in the Blue Box - Brooks Andrews (OH0056)

- Playing outdoors, picnics, grocery stores - Junkoh Harui (OH0058)