Manzanar Relocation Center Sign

Bainbridge Islanders arrived at Manzanar as it was still being constructed, the living quarters long barracks designed to house four families in 20'x20' rooms. Eventually 10,000 people would reside within the square mile of camp. At the edge of the Sierra Nevadas, Manzanar was a dusty expanse of barracks surrounded by barbed wire and watch towers manned by soldiers and searchlights, pointing in. Almost all of the remaining inmates were from California, many accustomed to city life.

The farm families from the Northwest found little in common with them, and by 1943 had successfully petitioned to transfer to Minidoka in southern Idaho, where the others from Washington and Oregon were incarcerated. To be near family members from California, five Island families chose to remain at Manzanar. Minidoka was similar to Manzanar: dusty and hot in the summer, muddy and cold in the winter.

Slideshows

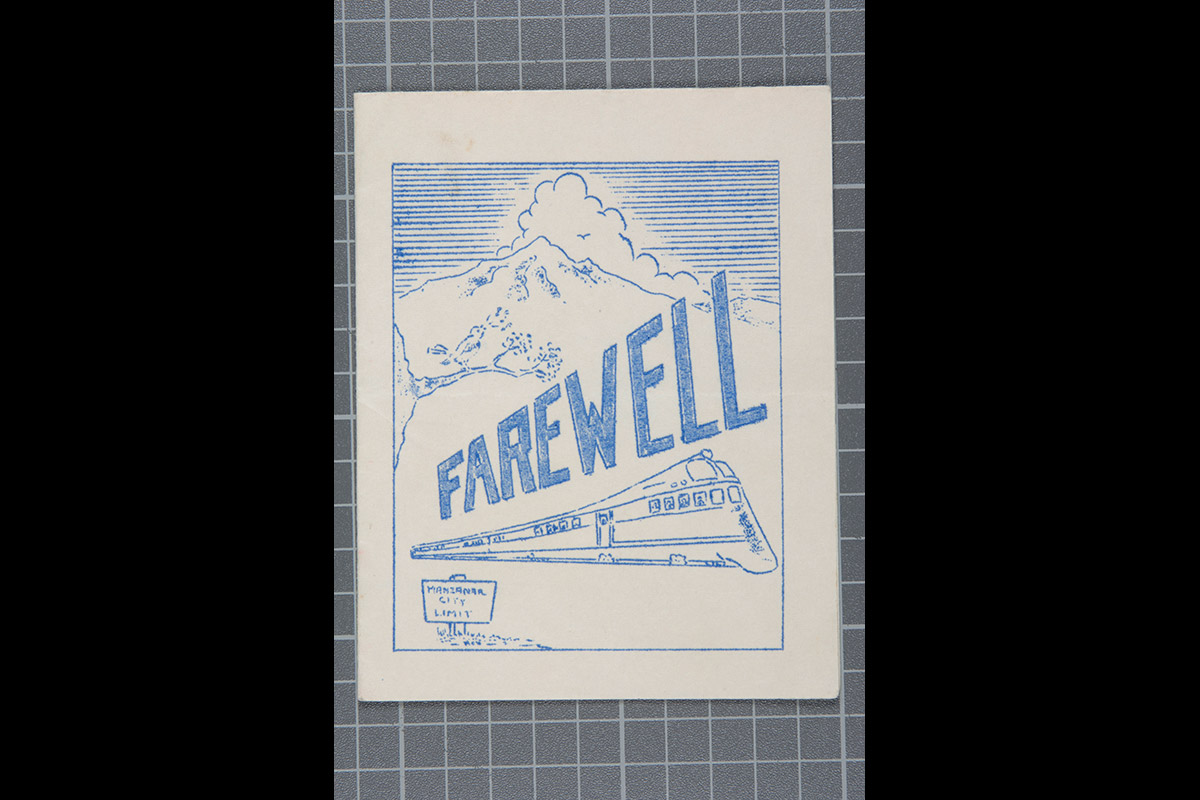

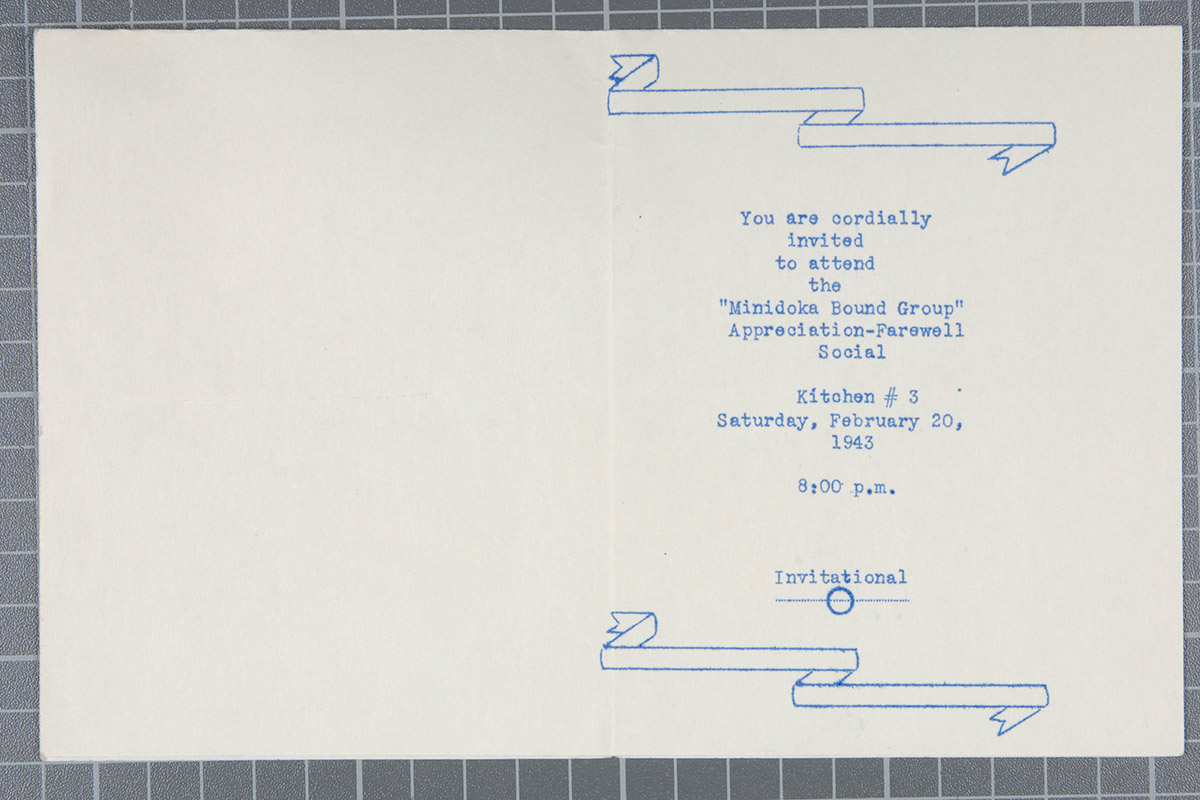

This is an invitation to a party thrown to bid farewell to the group of families from Bainbridge Island that left Manzanar in February of 1943 to go to Minidoka, Idaho.

This is an invitation to a party thrown to bid farewell to the group of families from Bainbridge Island that left Manzanar in February of 1943 to go to Minidoka, Idaho. As Manzanar became more settled, the imprisoned Nikkei were able to organize social activities such as this farewell party. Events were often held in the mess halls as well as barracks set aside as recreational centers.

As Manzanar became more settled, the imprisoned Nikkei were able to organize social activities such as this farewell party. Events were often held in the mess halls as well as barracks set aside as recreational centers. After a few months classrooms were set up at Manzanar. Initially there were no books, supplies, or even desks. Kids sat on the floor and older students taught the younger ones. Eventually, formal schools were opened. Caucasian teachers were brought in and lived in housing inside the camp.

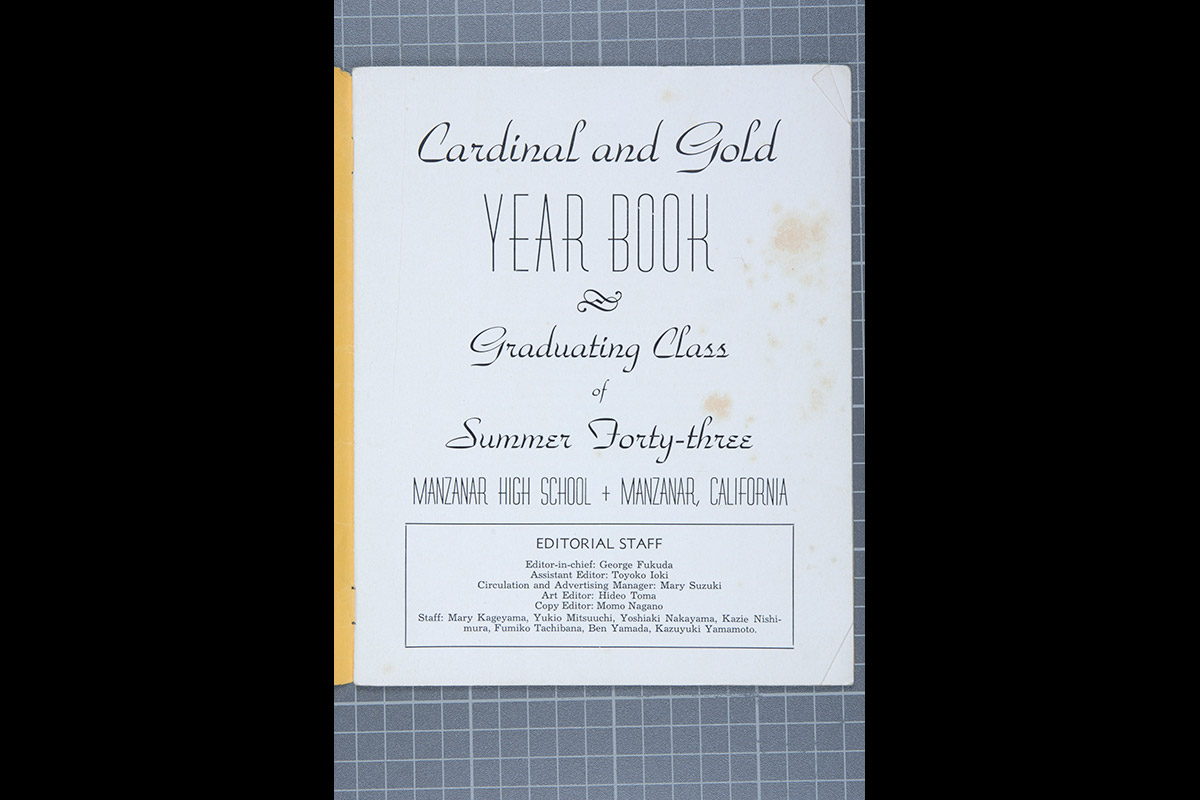

After a few months classrooms were set up at Manzanar. Initially there were no books, supplies, or even desks. Kids sat on the floor and older students taught the younger ones. Eventually, formal schools were opened. Caucasian teachers were brought in and lived in housing inside the camp. The class of '43 was the first to graduate from Manzanar High School. For the BI class of ’42, thirteen chairs were left empty during their graduation ceremony back on BI in honor of their Japanese classmates incarcerated in Manzanar.

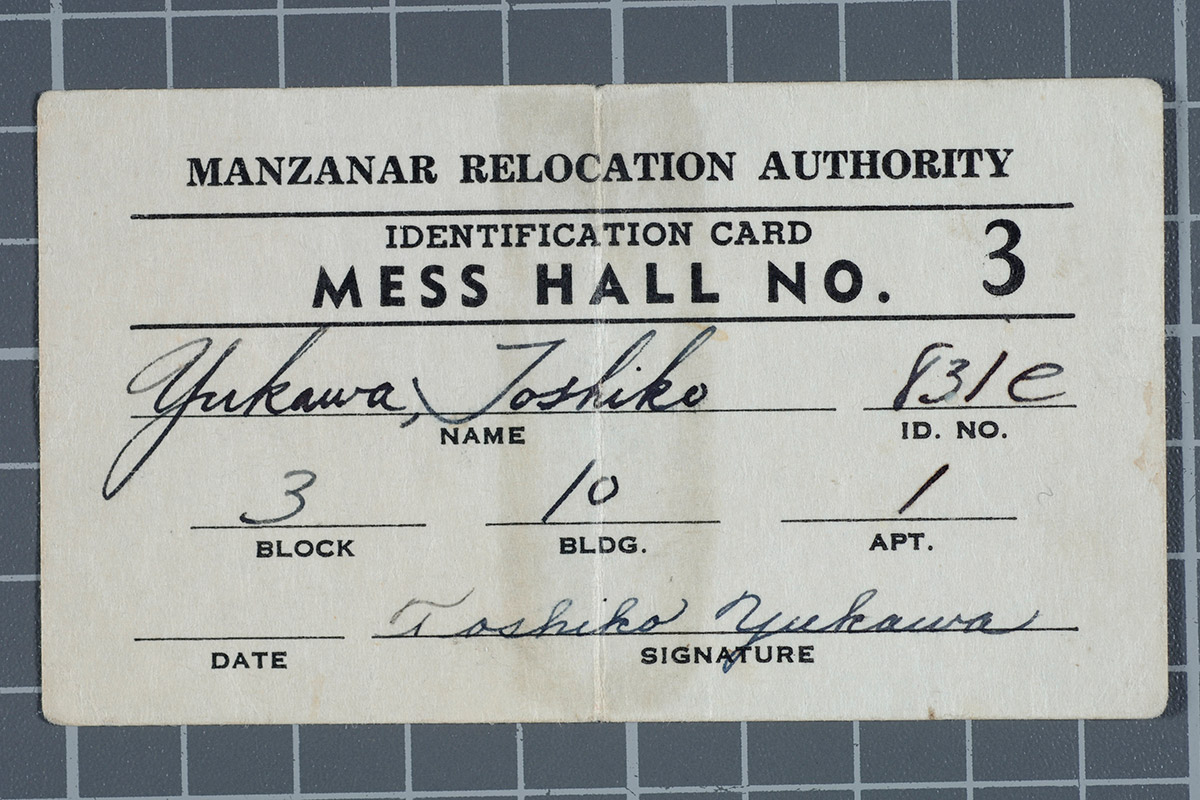

The class of '43 was the first to graduate from Manzanar High School. For the BI class of ’42, thirteen chairs were left empty during their graduation ceremony back on BI in honor of their Japanese classmates incarcerated in Manzanar. Issued to Toshiko Yukawa, age 12. All residents of Manzanar ate in mess halls at set meal times. Although required to eat in the mess hall of their block, some teenagers soon discovered which kitchens had the best cooks and would often sneak into those lines in search of better food.

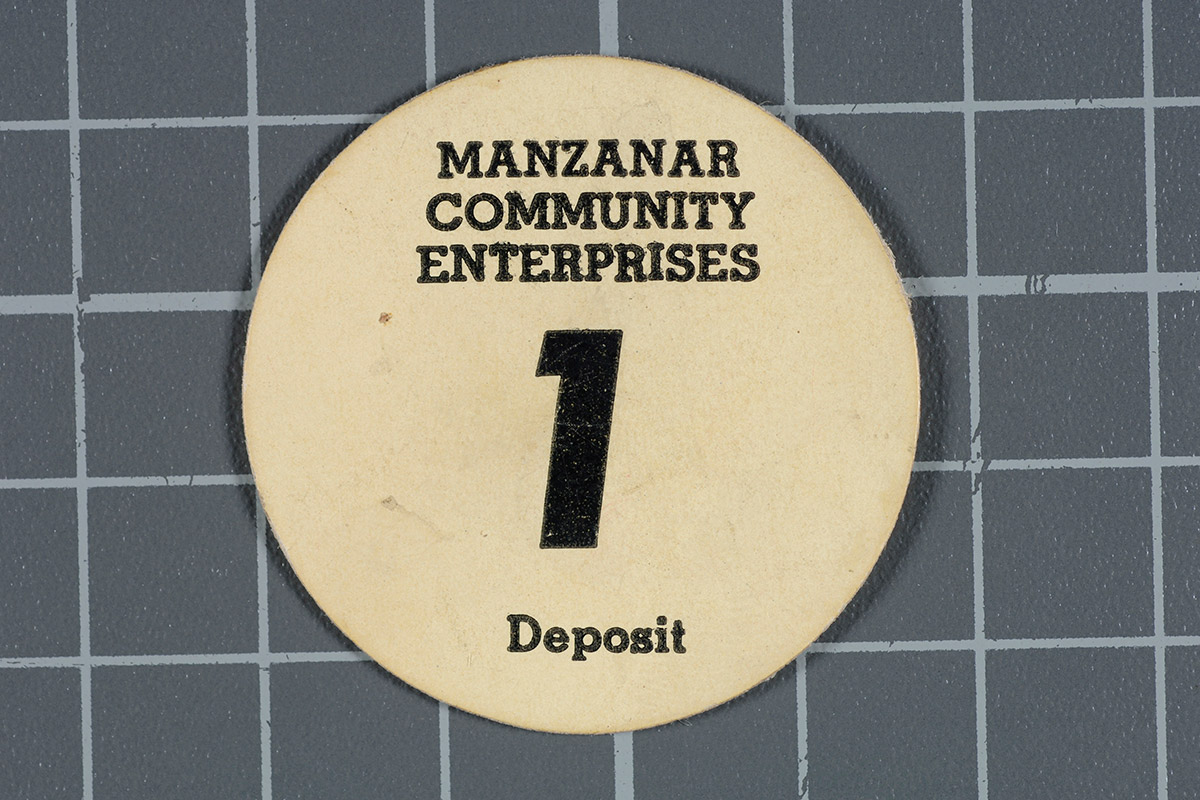

Issued to Toshiko Yukawa, age 12. All residents of Manzanar ate in mess halls at set meal times. Although required to eat in the mess hall of their block, some teenagers soon discovered which kitchens had the best cooks and would often sneak into those lines in search of better food. Consumer needs of the evacuees were served by the Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises, Inc., established on September 2, 1942. Initially operating a canteen and general store, by August 1944 this group supervised a variety of shops such as a shoe repair, watch repair, laundry, barber, beauty shop, dress shop, dry goods store, outdoor movie theater, sporting goods store, flower shop, and gift shop.

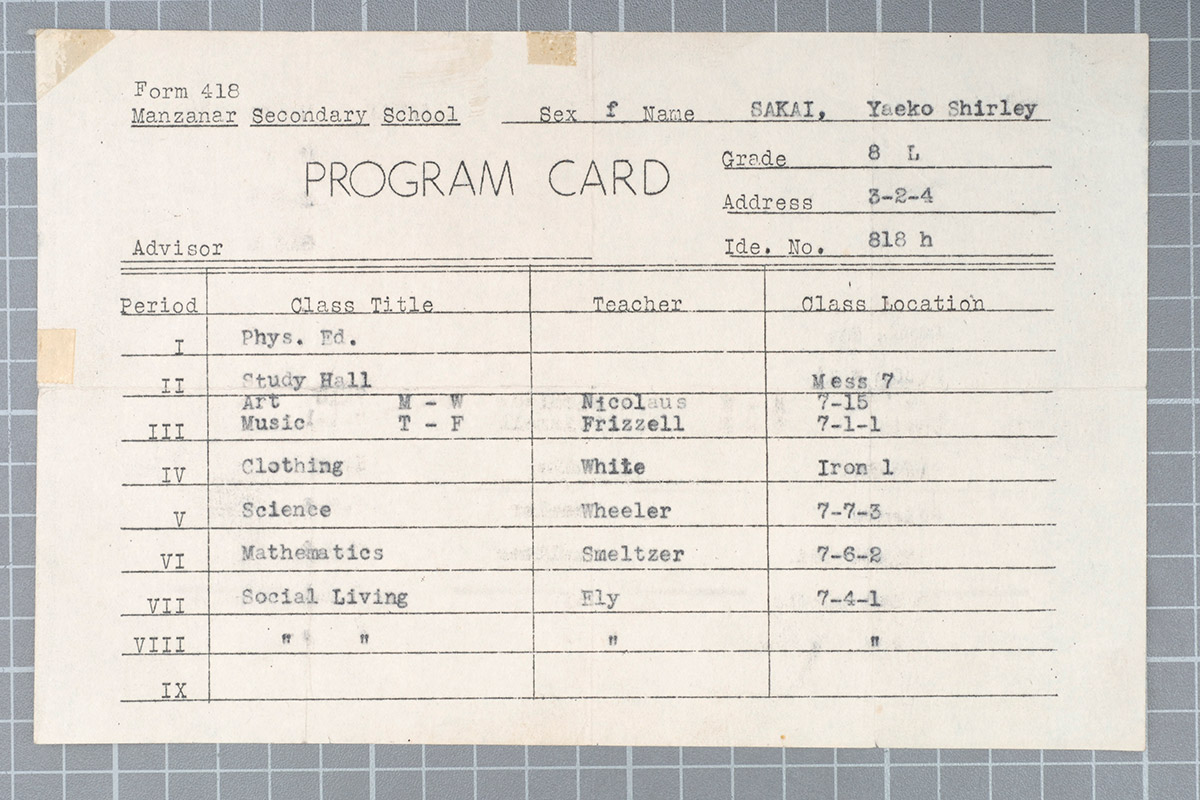

Consumer needs of the evacuees were served by the Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises, Inc., established on September 2, 1942. Initially operating a canteen and general store, by August 1944 this group supervised a variety of shops such as a shoe repair, watch repair, laundry, barber, beauty shop, dress shop, dry goods store, outdoor movie theater, sporting goods store, flower shop, and gift shop. Yaeko Sakai attended 8th grade at Manzanar Secondary School until she and her family were moved to Minidoka in February of 1943. Many students do not recall much about their schooling in the camps. It gave them something to break up the monotony of camp life.

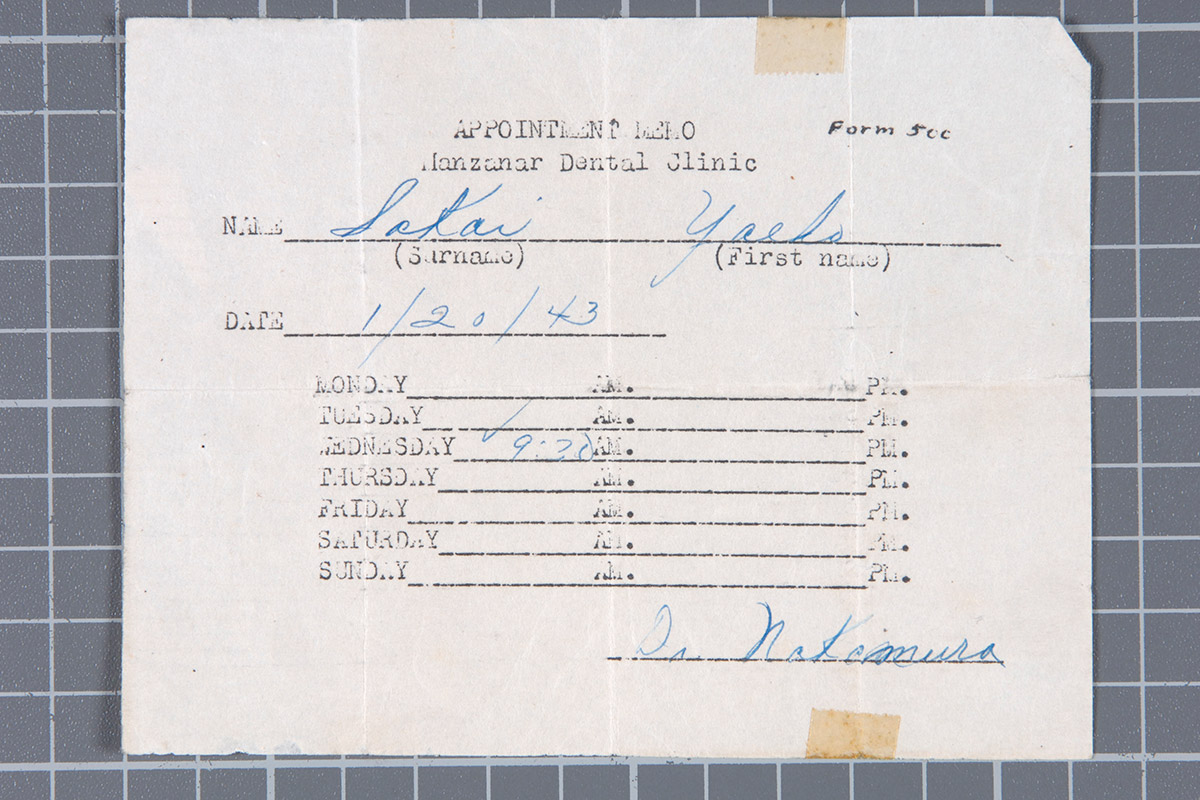

Yaeko Sakai attended 8th grade at Manzanar Secondary School until she and her family were moved to Minidoka in February of 1943. Many students do not recall much about their schooling in the camps. It gave them something to break up the monotony of camp life. Dentist appointment for Yaeko Sakai to go see Dr. Nakamura at the Manzanar Dental Clinic on Jan 20, 1943. Initially the hospital and medical clinics were run by evacuee doctors. Eventually Caucasian doctors were brought in to replace the Japanese American doctors.

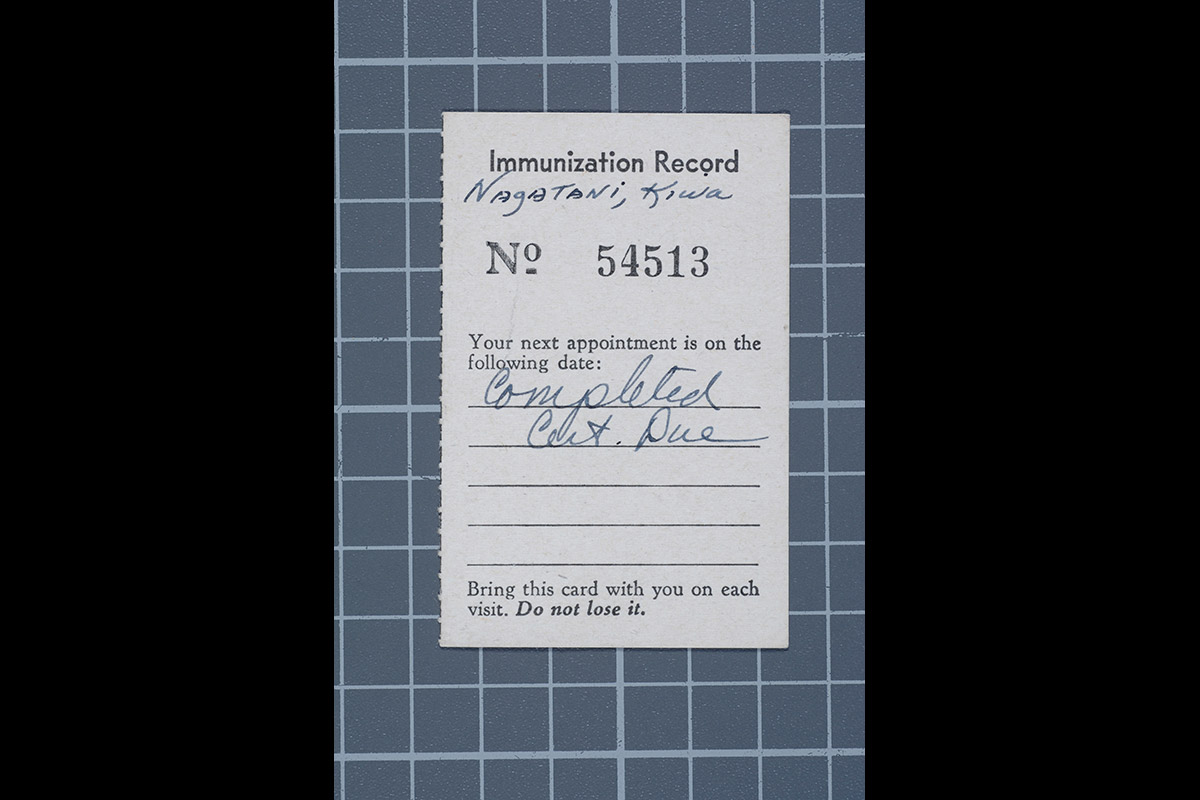

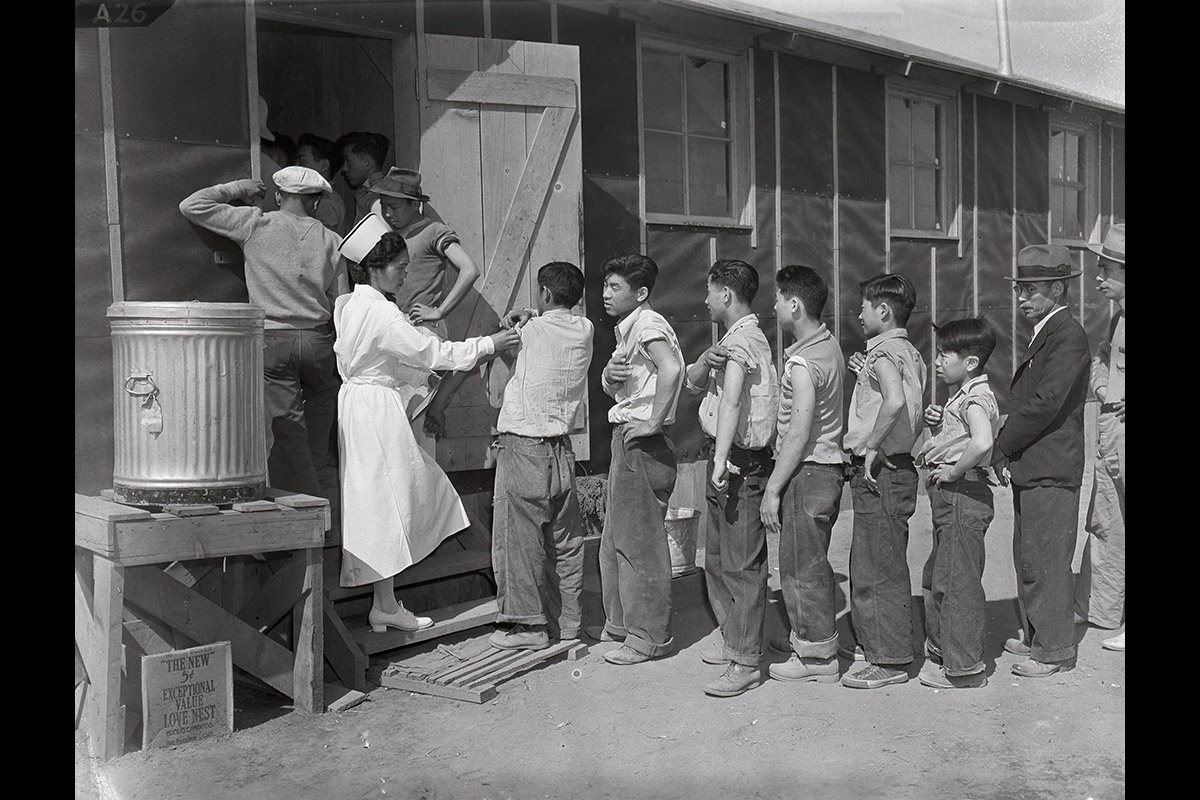

Dentist appointment for Yaeko Sakai to go see Dr. Nakamura at the Manzanar Dental Clinic on Jan 20, 1943. Initially the hospital and medical clinics were run by evacuee doctors. Eventually Caucasian doctors were brought in to replace the Japanese American doctors. For Kiwa Nagatani. Upon arrival at Manzanar, all residents had to be updated with their inoculations.

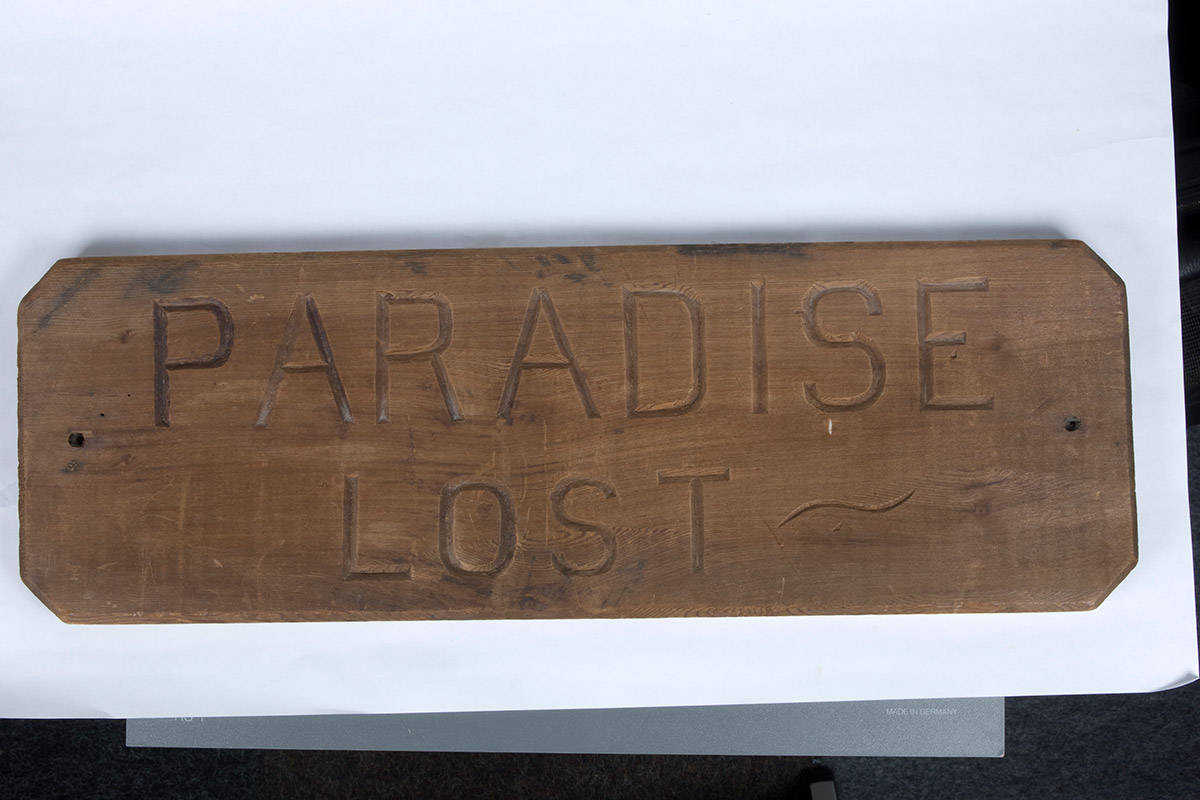

For Kiwa Nagatani. Upon arrival at Manzanar, all residents had to be updated with their inoculations. Those imprisoned at Manzanar made great efforts to make their surroundings more comfortable and home-like. This sign, hand carved by Ichiro Nagatani, makes a statement about his bleak environment.

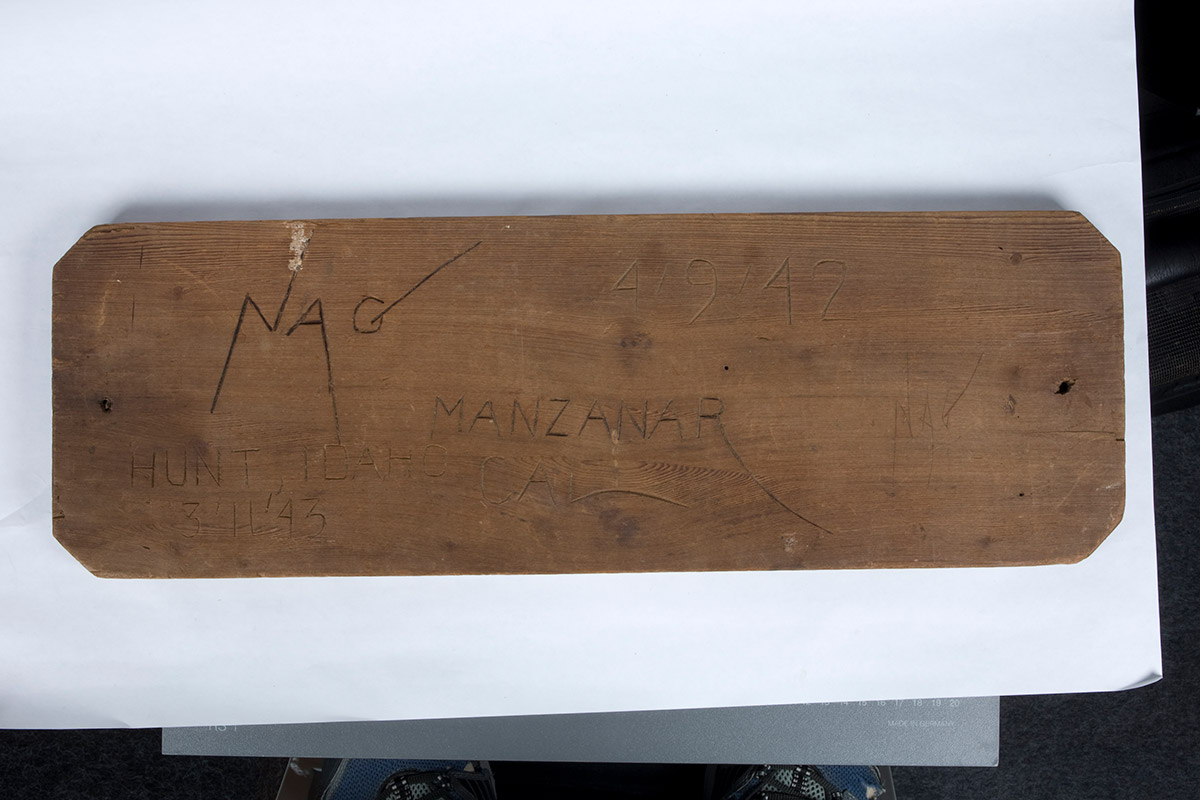

Those imprisoned at Manzanar made great efforts to make their surroundings more comfortable and home-like. This sign, hand carved by Ichiro Nagatani, makes a statement about his bleak environment. "Nag," Ichiro Nagatani's nickname, is carved to indicate who made this sign. Used to working all day on their farms, many of the Islanders sought work or took up hobbies such as carving to keep them occupied. Many of the older Issei took courses in English language, needlework, sewing, or cooking.

"Nag," Ichiro Nagatani's nickname, is carved to indicate who made this sign. Used to working all day on their farms, many of the Islanders sought work or took up hobbies such as carving to keep them occupied. Many of the older Issei took courses in English language, needlework, sewing, or cooking. Carved by Ichiro Nagatani in Manzanar. This sign was hung outside his family's apartment in Manzanar and later in Mindoka. Many families had similar nameplates. These helped personalize the otherwise uniform barracks.

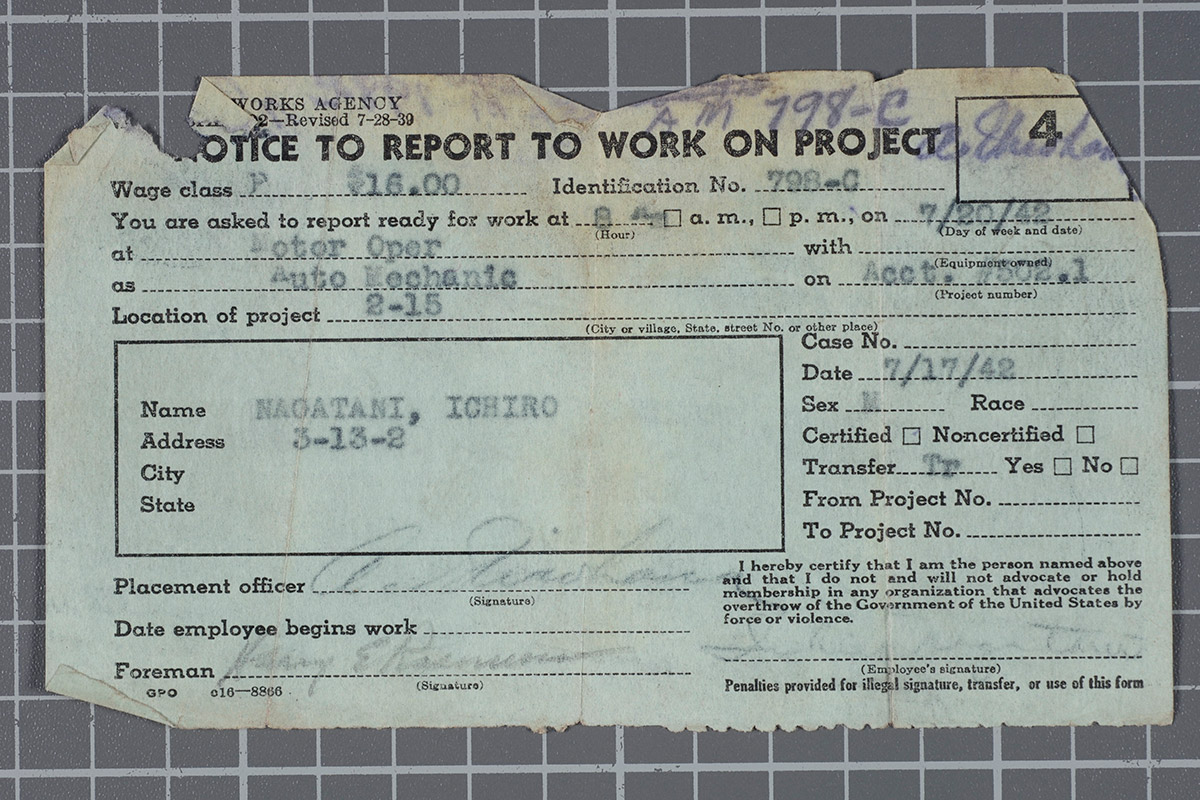

Carved by Ichiro Nagatani in Manzanar. This sign was hung outside his family's apartment in Manzanar and later in Mindoka. Many families had similar nameplates. These helped personalize the otherwise uniform barracks. Issued to Ichiro Nagatani to work as a motor operator in Manzanar. July 20, 1942. Right away all able bodied men and women from Bainbridge Island found work at Manzanar. Unskilled laborers were paid $12 a month. Skilled laborers such as carpenters, nurses, and cooks received $16 a month. Professional employees such as doctors, engineers, and managers were paid $19 a month.

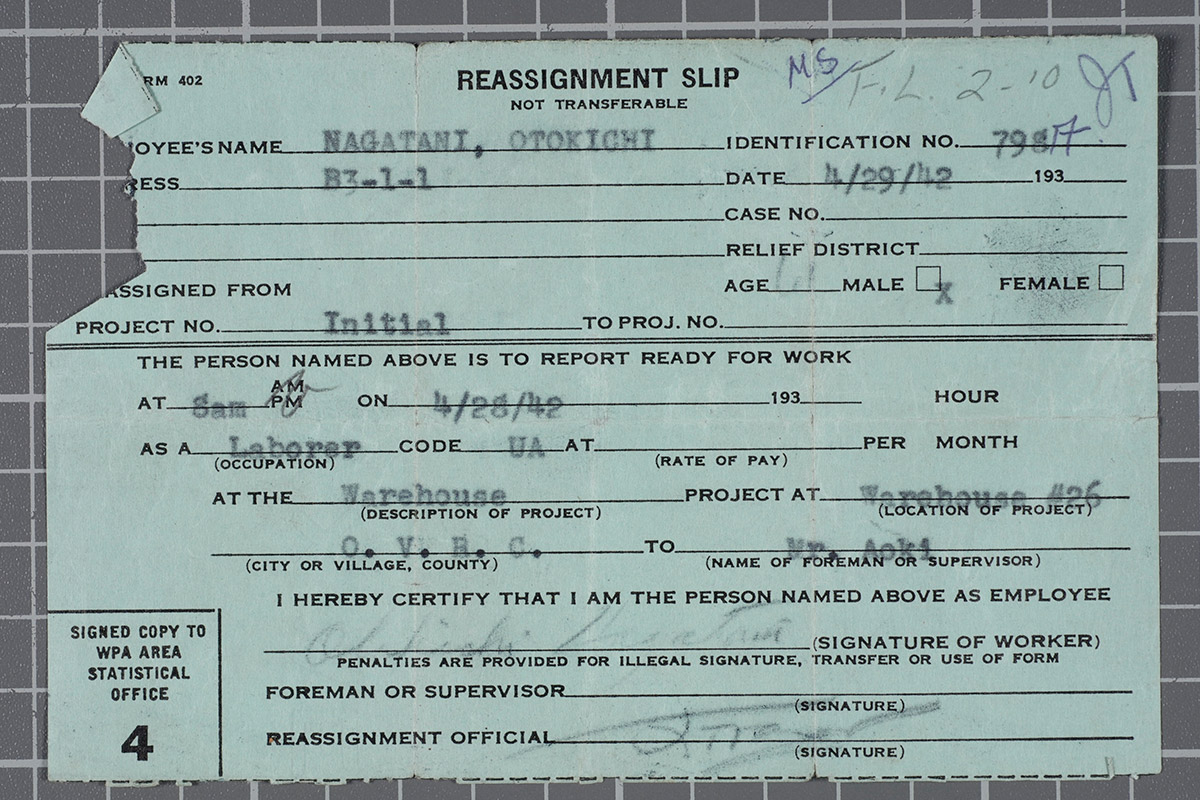

Issued to Ichiro Nagatani to work as a motor operator in Manzanar. July 20, 1942. Right away all able bodied men and women from Bainbridge Island found work at Manzanar. Unskilled laborers were paid $12 a month. Skilled laborers such as carpenters, nurses, and cooks received $16 a month. Professional employees such as doctors, engineers, and managers were paid $19 a month. Permission to work as a laborer in the warehouse in Manzanar. Issued to Otokichi Nagatani. April 29, 1942. Typical jobs for the young women were kitchen helper, nursery teacher, clerical worker, and nursing assistant. For the young men typical jobs were freight hand, truck driver, camp maintenance, carpenter, plumber, warehouse clerk.

Permission to work as a laborer in the warehouse in Manzanar. Issued to Otokichi Nagatani. April 29, 1942. Typical jobs for the young women were kitchen helper, nursery teacher, clerical worker, and nursing assistant. For the young men typical jobs were freight hand, truck driver, camp maintenance, carpenter, plumber, warehouse clerk.

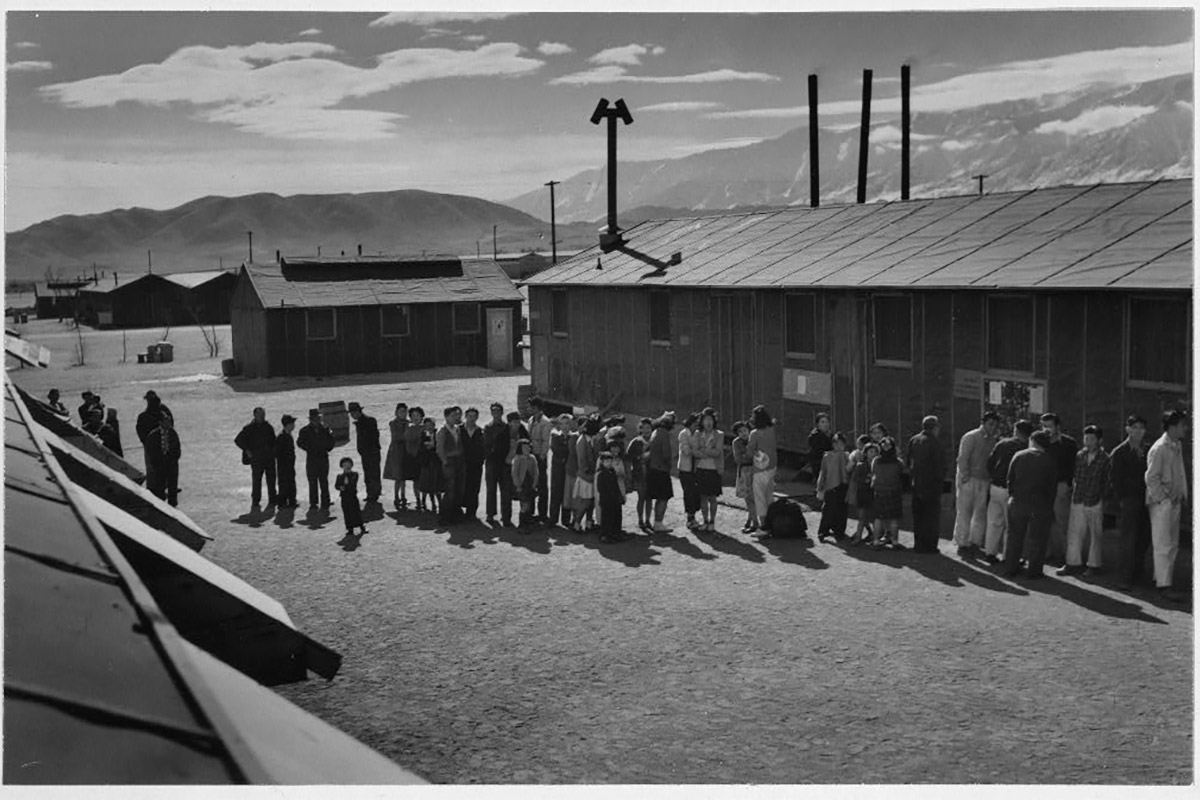

Manzanar was the first government facility to be constructed. It was originally a "Reception" center where evacuees would be held before being sent to various "Relocation" centers. Later Manzanar would become a permanent "Relocation" center housing over 10,000 people of Japanese descent. (Photo by Ansel Adams, Credit: Library of Congress)

Manzanar was the first government facility to be constructed. It was originally a "Reception" center where evacuees would be held before being sent to various "Relocation" centers. Later Manzanar would become a permanent "Relocation" center housing over 10,000 people of Japanese descent. (Photo by Ansel Adams, Credit: Library of Congress) When the Bainbridge Islanders arrived at Manzanar on April 1, 1942, only a small portion of the camp was complete. The Islanders saw a view similar to this scene as they arrived by bus to their new "home." (Photo by Ansel Adams, Credit: National Archives)

When the Bainbridge Islanders arrived at Manzanar on April 1, 1942, only a small portion of the camp was complete. The Islanders saw a view similar to this scene as they arrived by bus to their new "home." (Photo by Ansel Adams, Credit: National Archives) Almost everyone who lived in Manzanar remembers the dust storms. As the wood on the newly constructed barracks aged and shrank, gaps appeared in between the planks. Dust would get into the food in the mess halls and into the living apartments.

Almost everyone who lived in Manzanar remembers the dust storms. As the wood on the newly constructed barracks aged and shrank, gaps appeared in between the planks. Dust would get into the food in the mess halls and into the living apartments. Manzanar was located in the shadows of the majestic Sierra Nevada mountains. Many of those imprisoned here never appreciated the beauty surrounding them due to the barbed wire and guard towers that lay between them and the mountains. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Credit: Library of Congress)

Manzanar was located in the shadows of the majestic Sierra Nevada mountains. Many of those imprisoned here never appreciated the beauty surrounding them due to the barbed wire and guard towers that lay between them and the mountains. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Credit: Library of Congress) April 2 1942. These young men are all from Bainbridge: on steps in hat: a Sakuma. Boys lined up left to right: Unknown, Robert Koba, Morio Terayama, Kazuo Terayama, Vic Takemoto, Bill Takemoto. (Photo by Clem Albers. National Archives and Records Administration)

April 2 1942. These young men are all from Bainbridge: on steps in hat: a Sakuma. Boys lined up left to right: Unknown, Robert Koba, Morio Terayama, Kazuo Terayama, Vic Takemoto, Bill Takemoto. (Photo by Clem Albers. National Archives and Records Administration) Fujiko Koba models her geta for Yaeko Yamashita (both of Bainbridge Island). Geta were useful for helping to keep feet out of the dust and mud. (Photo by Clem Albers. National Archives and Records Administration)

Fujiko Koba models her geta for Yaeko Yamashita (both of Bainbridge Island). Geta were useful for helping to keep feet out of the dust and mud. (Photo by Clem Albers. National Archives and Records Administration) Some young women from Bainbridge Island stop to pose for a photo as they hang curtains in their barracks apartment. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Some young women from Bainbridge Island stop to pose for a photo as they hang curtains in their barracks apartment. (Credit: Library of Congress) Nobuzo Koura died in Manzanar in May 1942, at the age of 68, just after arrival from Bainbridge Island. His remains are still buried there today.

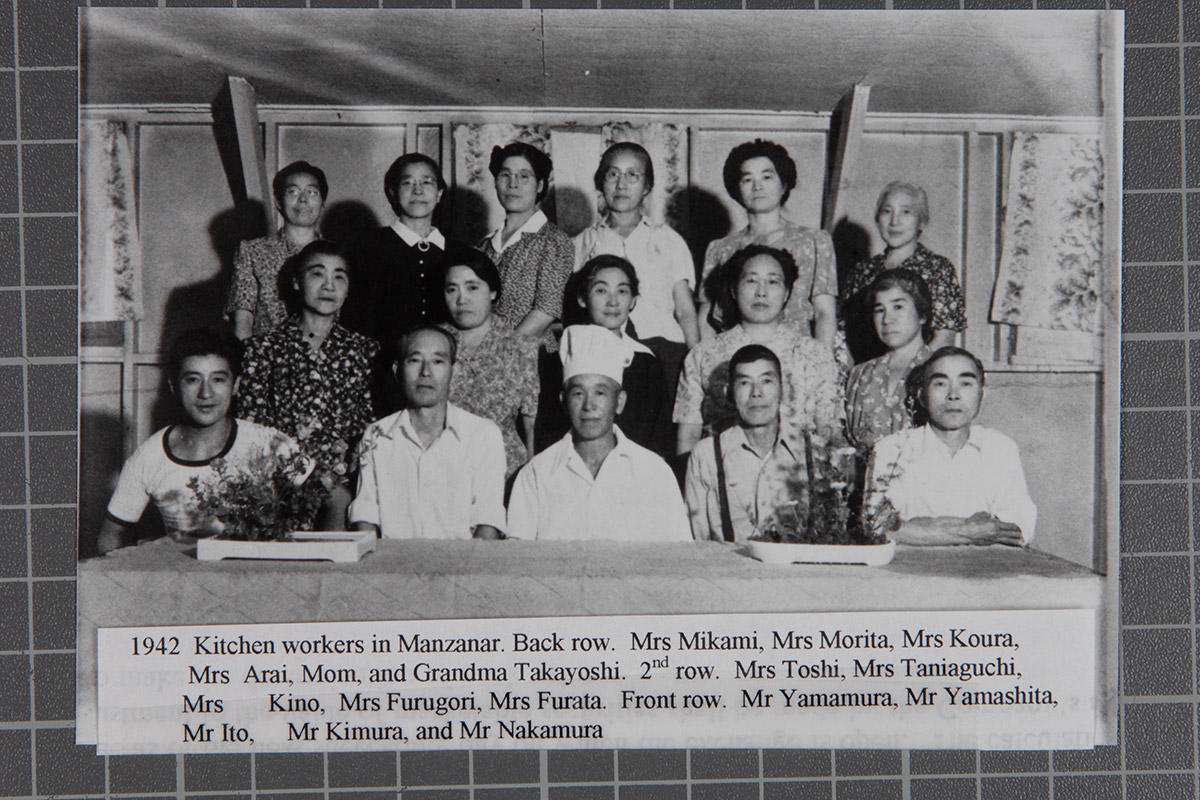

Nobuzo Koura died in Manzanar in May 1942, at the age of 68, just after arrival from Bainbridge Island. His remains are still buried there today. Used to the hard work on their farms back home, many Bainbridge Islander Issei could not stand the idleness of camp life. They found jobs, such as these kitchen workers, and took up hobbies such as needlepoint or carving.

Used to the hard work on their farms back home, many Bainbridge Islander Issei could not stand the idleness of camp life. They found jobs, such as these kitchen workers, and took up hobbies such as needlepoint or carving. The food served in the mess halls was difficult for many people to get used to. When the Japanese prisoners were allowed to become cooks and fresher items became available the food improved. (Photo by Clem Albers. National Archives and Records Administration)

The food served in the mess halls was difficult for many people to get used to. When the Japanese prisoners were allowed to become cooks and fresher items became available the food improved. (Photo by Clem Albers. National Archives and Records Administration) Another change the Japanese prisoners had to adjust to was eating as a group in a mess hall. Families no longer ate together as many children and young adults chose to sit with their friends instead. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress)

Another change the Japanese prisoners had to adjust to was eating as a group in a mess hall. Families no longer ate together as many children and young adults chose to sit with their friends instead. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress) With over 10,000 residents, Manzanar was a small city with many consumer needs. The Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises, Inc. was established on September 2, 1942 to meet these needs. It was operated by evacuees in space rented from the War Relocation Authority. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress)

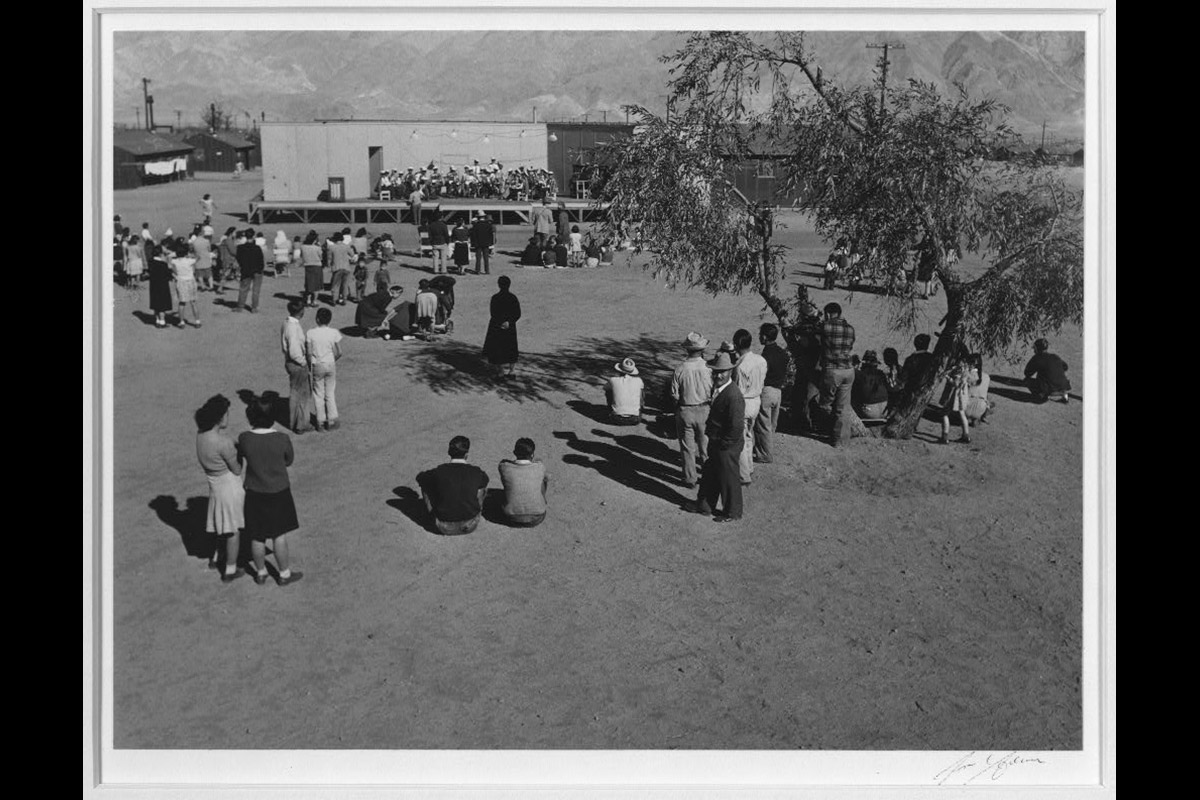

With over 10,000 residents, Manzanar was a small city with many consumer needs. The Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises, Inc. was established on September 2, 1942 to meet these needs. It was operated by evacuees in space rented from the War Relocation Authority. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress) To break up the monotony of camp life many forms of entertainment were organized such as this outdoor concert located in a firebreak between barracks. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress)

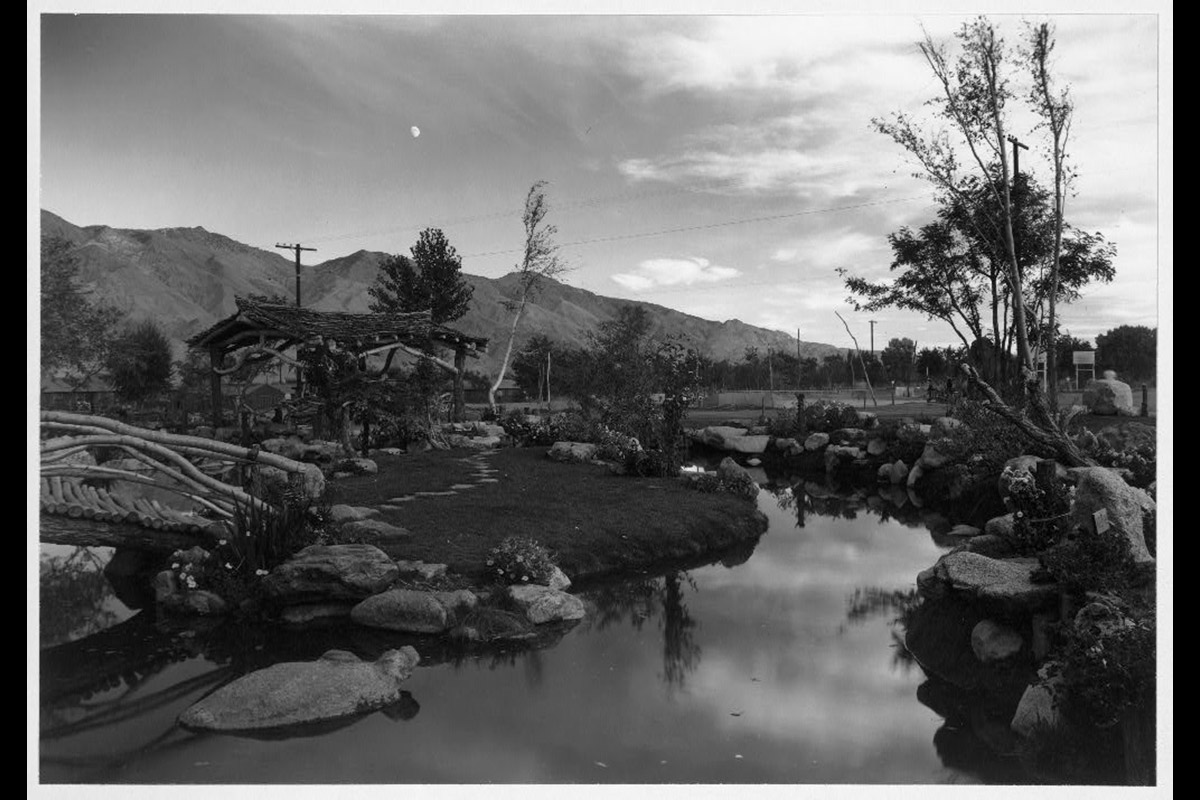

To break up the monotony of camp life many forms of entertainment were organized such as this outdoor concert located in a firebreak between barracks. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress) Evacuees got to work right away to try to make the drab and monotonous environment of Manzanar more hospitable. Lawns, flowers, and vegetable gardens were planted. Here, an entire park was built in the Japanese garden style. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress)

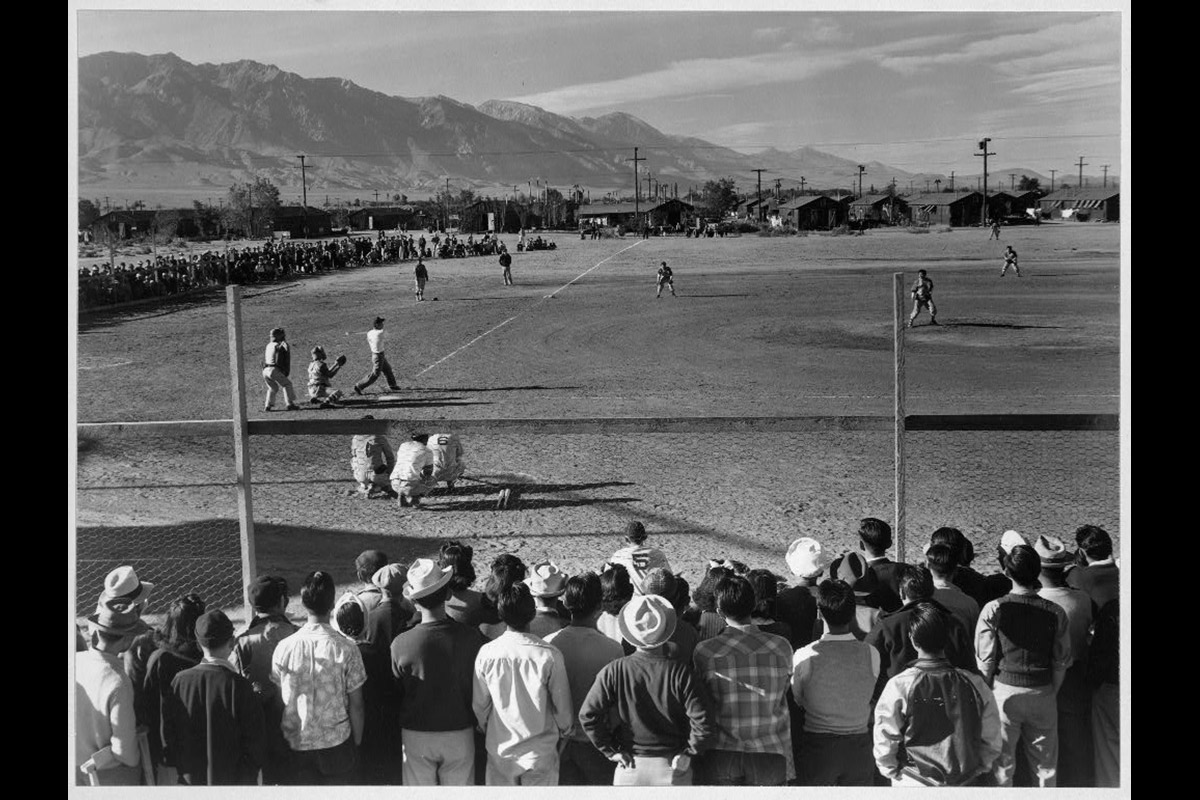

Evacuees got to work right away to try to make the drab and monotonous environment of Manzanar more hospitable. Lawns, flowers, and vegetable gardens were planted. Here, an entire park was built in the Japanese garden style. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress) A favorite past time when they were back home, baseball soon became a form of entertainment for evacuees of all ages. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress)

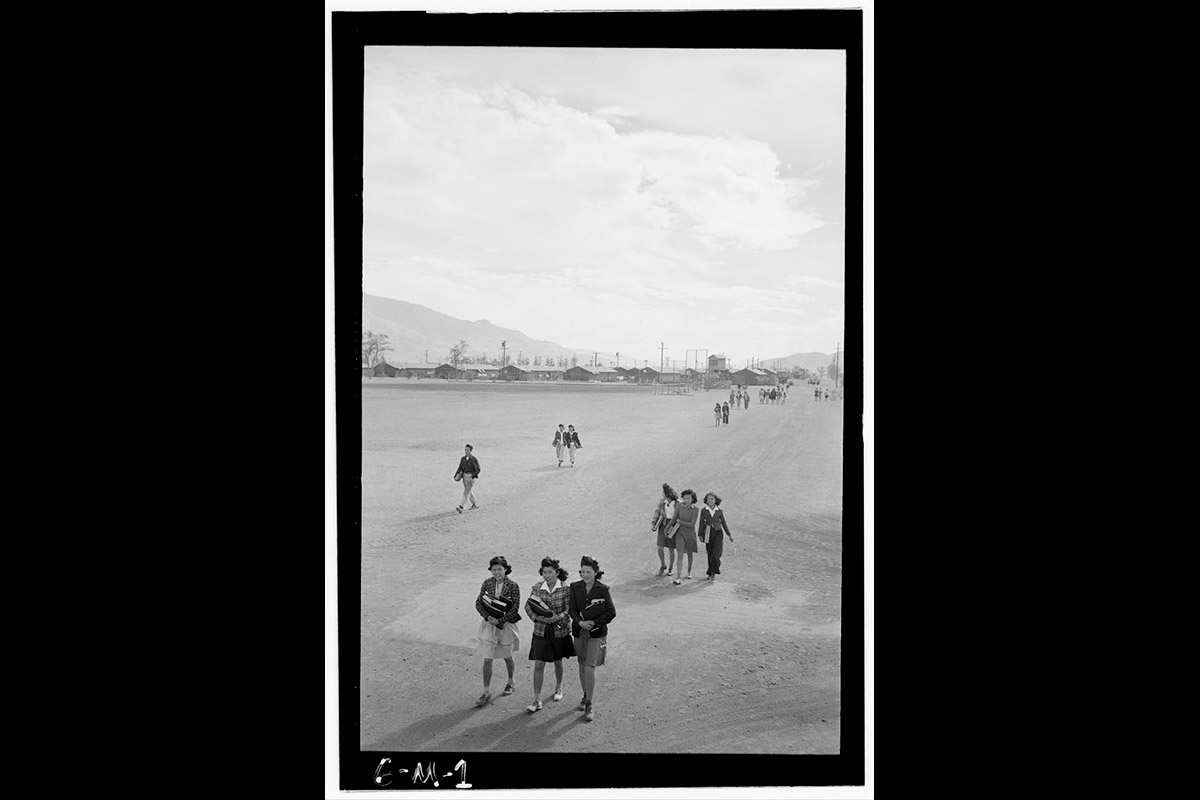

A favorite past time when they were back home, baseball soon became a form of entertainment for evacuees of all ages. (Photo by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress) Many recall walking to school in heavy dust storms. School was the main occupation for the younger camp prisoners. During the summer and in their spare time, many youth also found part time jobs as field-hands, nursing assistants, house cleaners for the camp administrators, maintenance personnel, truck drivers, and clerical workers.

Many recall walking to school in heavy dust storms. School was the main occupation for the younger camp prisoners. During the summer and in their spare time, many youth also found part time jobs as field-hands, nursing assistants, house cleaners for the camp administrators, maintenance personnel, truck drivers, and clerical workers. Manzanar. Block 3. Though the Bainbridge Islanders were not allowed to bring their pets with them, this restriction was later relaxed. Here Shima has found a small kitten to adopt as her own.

Manzanar. Block 3. Though the Bainbridge Islanders were not allowed to bring their pets with them, this restriction was later relaxed. Here Shima has found a small kitten to adopt as her own. Manzanar. Block 3. The Nishimori family stayed in Manzanar and did not move to Mindoka with the rest of the Bainbridge Islanders. In the background are examples of landscaping evacuees installed to help beautify their environment.

Manzanar. Block 3. The Nishimori family stayed in Manzanar and did not move to Mindoka with the rest of the Bainbridge Islanders. In the background are examples of landscaping evacuees installed to help beautify their environment. Manzanar. Block 3. In the background are Hiro and Susan Hayashida standing on the steps of the Hayashida family apartment.

Manzanar. Block 3. In the background are Hiro and Susan Hayashida standing on the steps of the Hayashida family apartment. As they had back home, many of the Nisei women helped entertain and look after the younger children. Here a group from Bainbridge Island poses for a photo on the lawn in front of one of the barracks.

As they had back home, many of the Nisei women helped entertain and look after the younger children. Here a group from Bainbridge Island poses for a photo on the lawn in front of one of the barracks. Several weddings were held in camp. Brides either ordered their gowns through a catalog store or they were sewn in camp. News of these happy occasions made it back to friends and neighbors at home on Bainbridge Island thanks to the regular columns in the Bainbridge Review.

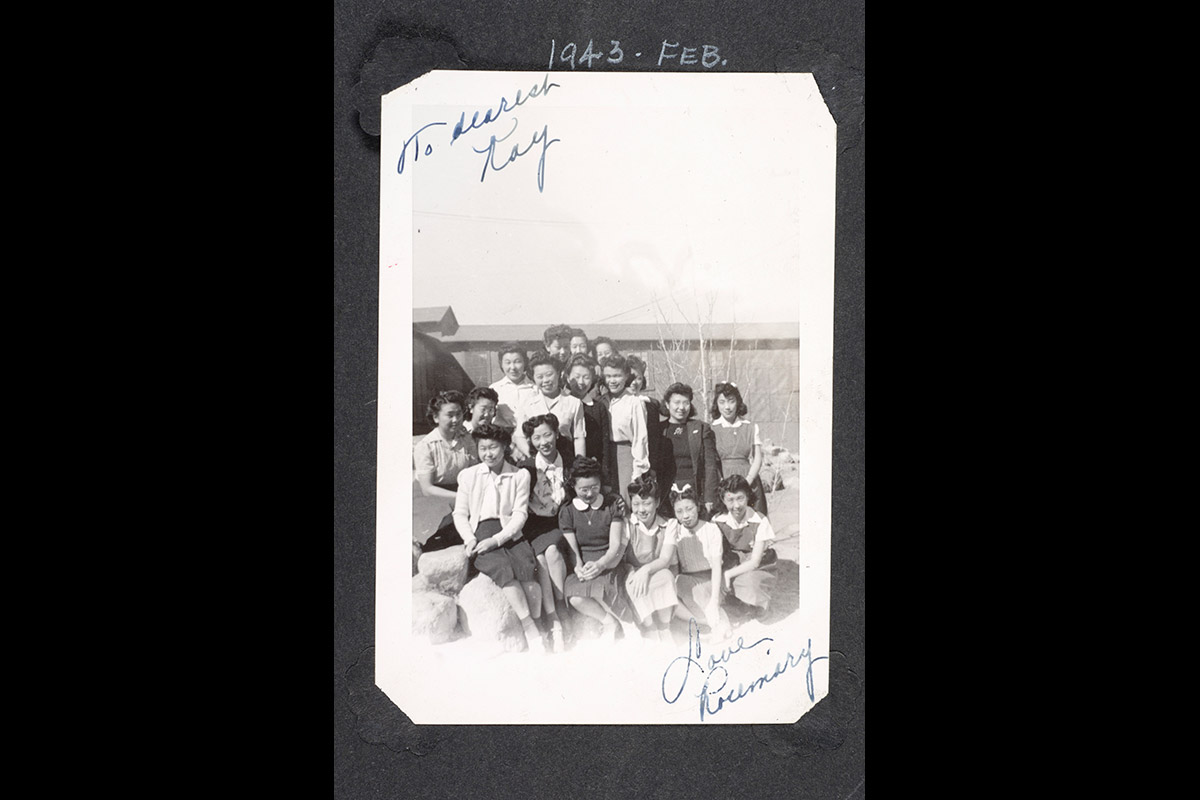

Several weddings were held in camp. Brides either ordered their gowns through a catalog store or they were sewn in camp. News of these happy occasions made it back to friends and neighbors at home on Bainbridge Island thanks to the regular columns in the Bainbridge Review. Kay Sakai of Bainbridge Island is third from the left in the front.

Kay Sakai of Bainbridge Island is third from the left in the front. Kay Sakai worked in the hospital during the short time she was in Manzanar. Her co-workers mailed this photo to her after she had moved to Minidoka. They are sitting in a Japanese style garden planted in between barracks.

Kay Sakai worked in the hospital during the short time she was in Manzanar. Her co-workers mailed this photo to her after she had moved to Minidoka. They are sitting in a Japanese style garden planted in between barracks. Kay Sakai, Tak Shindo, Toshiko Mikami. This is another example of the beautification efforts at Manzanar.

Kay Sakai, Tak Shindo, Toshiko Mikami. This is another example of the beautification efforts at Manzanar.

This packing trunk belonged to the Henry Takayoshi family and was used at the Minidoka "Relocation" Center. After time friends were able to ship or bring items to prisoners from back home. The Takayoshis also used this trunk as they traveled from Minidoka to Renton, WA where they settled after the war. (Credit: Bainbridge Island Historical Society. Photographed by Fenwick Publishing)

This packing trunk belonged to the Henry Takayoshi family and was used at the Minidoka "Relocation" Center. After time friends were able to ship or bring items to prisoners from back home. The Takayoshis also used this trunk as they traveled from Minidoka to Renton, WA where they settled after the war. (Credit: Bainbridge Island Historical Society. Photographed by Fenwick Publishing) Carved by Ichiro Nagatani in Manzanar. This sign was hung outside his family's apartment in Manzanar and later in Mindoka. Many families had similar nameplates. These helped personalize the otherwise uniform barracks.

Carved by Ichiro Nagatani in Manzanar. This sign was hung outside his family's apartment in Manzanar and later in Mindoka. Many families had similar nameplates. These helped personalize the otherwise uniform barracks. Those imprisoned at Manzanar made great efforts to make their surroundings more comfortable and home-like. This sign, hand carved by Ichiro Nagatani, makes a statement about his bleak environment.

Those imprisoned at Manzanar made great efforts to make their surroundings more comfortable and home-like. This sign, hand carved by Ichiro Nagatani, makes a statement about his bleak environment. "Nag," Ichiro Nagatani's nickname, is carved to indicate who made this sign. Used to working all day on their farms, many of the Islanders sought work or took up hobbies such as carving to keep them occupied. Many of the older Issei took courses in English language, needlework, sewing, or cooking.

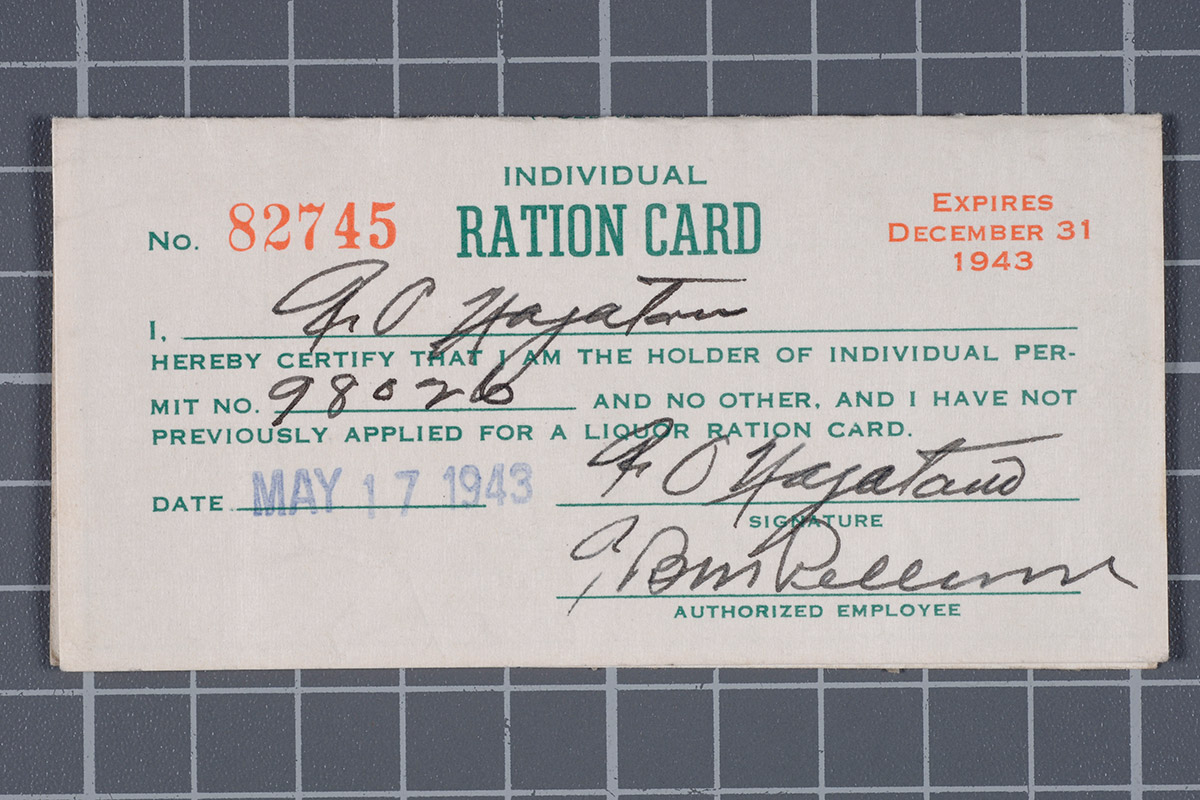

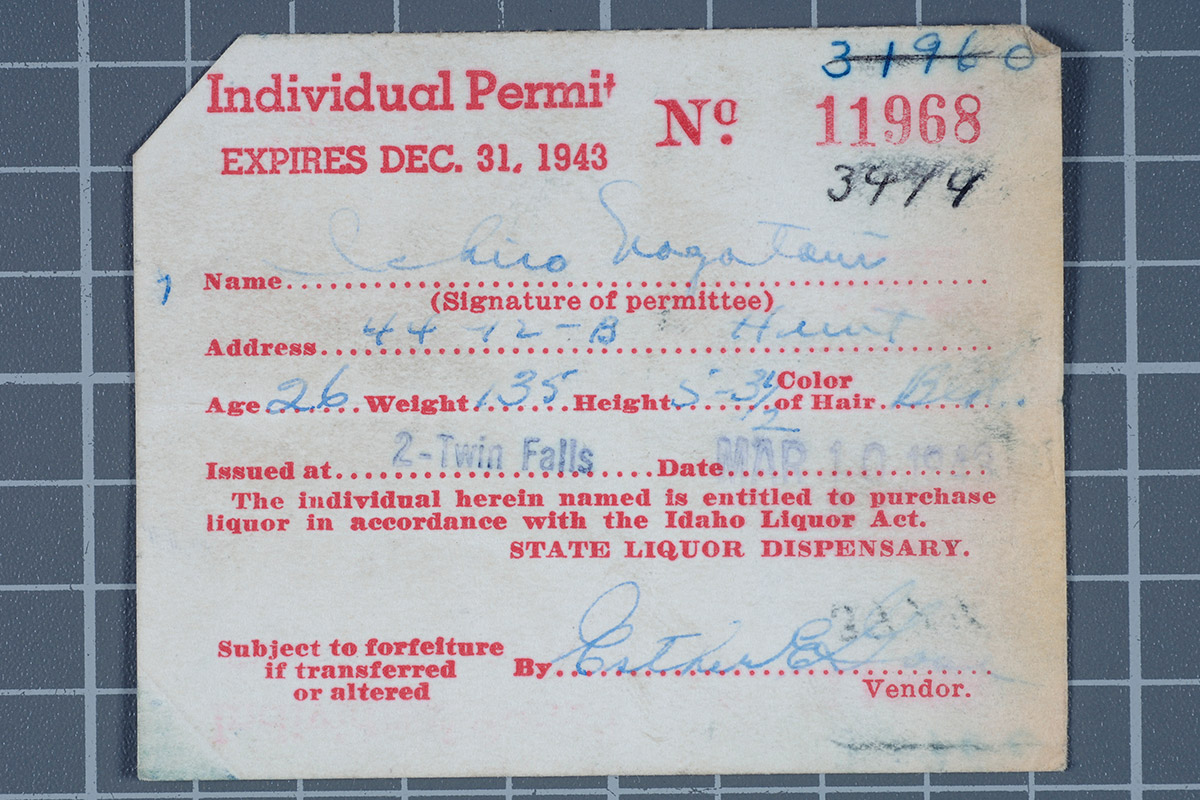

"Nag," Ichiro Nagatani's nickname, is carved to indicate who made this sign. Used to working all day on their farms, many of the Islanders sought work or took up hobbies such as carving to keep them occupied. Many of the older Issei took courses in English language, needlework, sewing, or cooking. Even while incarcerated in camp, evacuees were issued ration cards. They could get permits to leave Minidoka to travel to nearby Twin Falls, Idaho for shopping and rations.

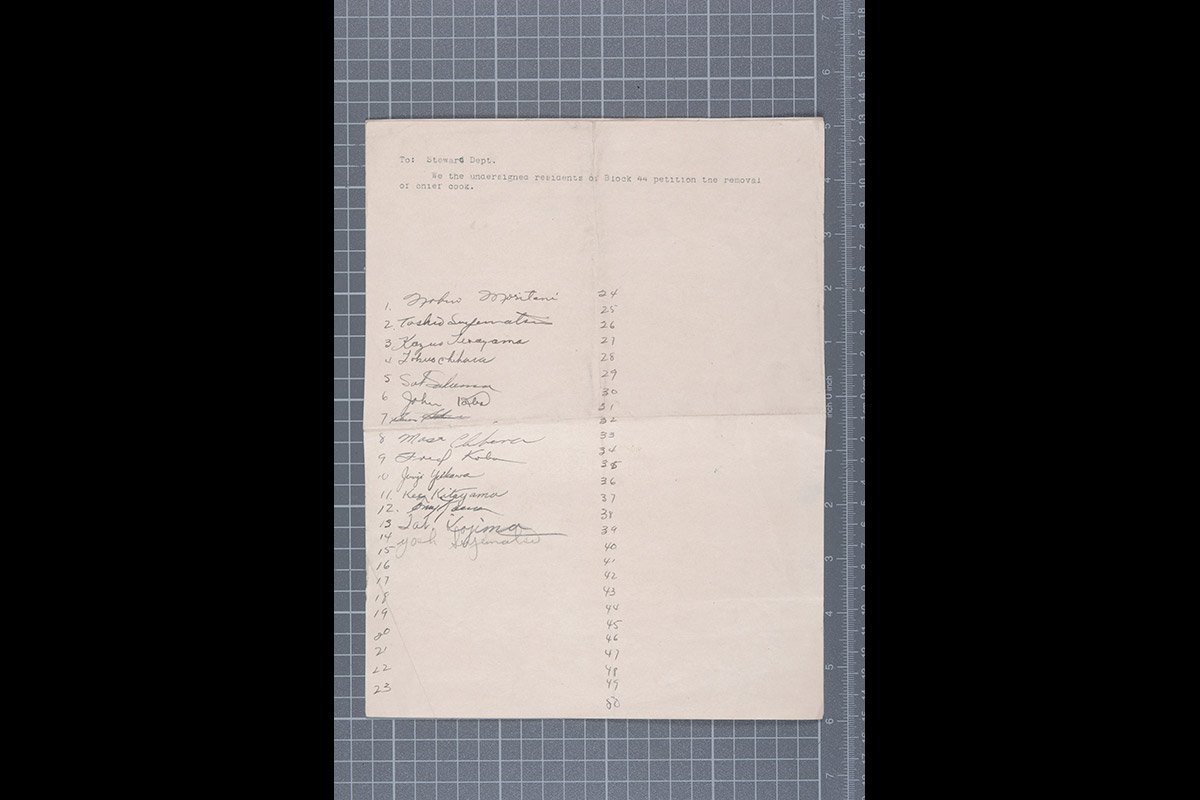

Even while incarcerated in camp, evacuees were issued ration cards. They could get permits to leave Minidoka to travel to nearby Twin Falls, Idaho for shopping and rations. Many of the Bainbridge Island Nisei were unhappy with the cook for Block 44 and made this petition. It is signed by Nobuo Moritani, Toshio Suyematsu, Kazuo Terayama, Toshio Chihara, Sat Sakuma, John Koba, Shun Sakuma, Masa Chihara, Fred Koba, Junji Yukawa, Kee Kitayama, Tony Koura, Tats Kojima, Yosh Suyematsu.

Many of the Bainbridge Island Nisei were unhappy with the cook for Block 44 and made this petition. It is signed by Nobuo Moritani, Toshio Suyematsu, Kazuo Terayama, Toshio Chihara, Sat Sakuma, John Koba, Shun Sakuma, Masa Chihara, Fred Koba, Junji Yukawa, Kee Kitayama, Tony Koura, Tats Kojima, Yosh Suyematsu. This was issued to Ichiro Nagatani and entitled him to purchase liquor in the state of Idaho. It expired on December 31, 1943.

This was issued to Ichiro Nagatani and entitled him to purchase liquor in the state of Idaho. It expired on December 31, 1943.

There is a stark contrast between the Issei (first generation) and Nisei (second generation) experiences in camp. Hardships fell primarily on the older Issei who lost their homes, livelihoods, and freedom. Forced to leave before harvesting what was to be a bumper strawberry crop, many Island Issei had no means of supporting their family or paying rent and thus lost their farmland. The widowed Masa Omoto soon found herself alone in camp while her four sons were away serving in the army. Many Issei couples, such as the Amatatsus, Kinos, and Nishis, were separated for the duration of the war because the men were interned in Department of Justice camps. Isseis, who were not permitted to hold leadership positions in camps, were forced to take a back seat to the younger Niseis.

For some of the younger Niseis, free from the daily chores of farming, camp–life proved to be a chance to explore new opportunities. Many took on leadership roles in camp, learned a trade such as nursing or carpentry, or enjoyed an extracurricular activity such as baseball or dancing. Some applied for indefinite leave from Minidoka for education, employment, or to join the army. These young adults from rural Bainbridge Island may never have left the Island and life as a farmer had it not been for the war. Perhaps the youngest camp residents had it the easiest. Parents shielded their children from the shame and humiliation of evacuation and tried to make their lives seem as normal as possible. Hisa Hayashida, age six, remembers a carefree youth where she could explore the camp and just had to open her front door to find many other playmates.

Though cameras were confiscated as contraband immediately after Pearl Harbor, later in the war the Japanese Americans were allowed to have and use them again. Many of the following images are family photos taken while in camp.

At the extreme left is a corner of the dining hall where the 275 to 300 residents of the block eat. Behind the dining hall is the sanitation building including showers, lavatories, toilets and washtubs. Nearly all the residents planted flowers and vegetable gardens in front of their barracks. (WRA photo. National Archives)

At the extreme left is a corner of the dining hall where the 275 to 300 residents of the block eat. Behind the dining hall is the sanitation building including showers, lavatories, toilets and washtubs. Nearly all the residents planted flowers and vegetable gardens in front of their barracks. (WRA photo. National Archives) December 9, 1942. Snow often blanketed the grounds of Minidoka. Children enjoyed sledding and ice-skating during the winter. (WRA photo. National Archives)

December 9, 1942. Snow often blanketed the grounds of Minidoka. Children enjoyed sledding and ice-skating during the winter. (WRA photo. National Archives) December 10, 1942. It was difficult to keep the barracks clean when the ground outside was so muddy. Traditional Japanese geta, or raised wooden platform shoes, were sometimes used to try to keep feet dry. Wooden planks were also set on the ground to serve as walkways. (WRA photo. National Archives)

December 10, 1942. It was difficult to keep the barracks clean when the ground outside was so muddy. Traditional Japanese geta, or raised wooden platform shoes, were sometimes used to try to keep feet dry. Wooden planks were also set on the ground to serve as walkways. (WRA photo. National Archives) Coal was brought in by train then delivered by truck to each block. These pot-bellied stoves were sufficient to warm the small apartments during the winter. (WRA photo. National Archives)

Coal was brought in by train then delivered by truck to each block. These pot-bellied stoves were sufficient to warm the small apartments during the winter. (WRA photo. National Archives) This is one of two water towers that served Minidoka. Water pumped to the towers from four wells was distributed to mess halls and the lavatory/laundry buildings in each block. August 18, 1942. (WRA photo. National Archives)

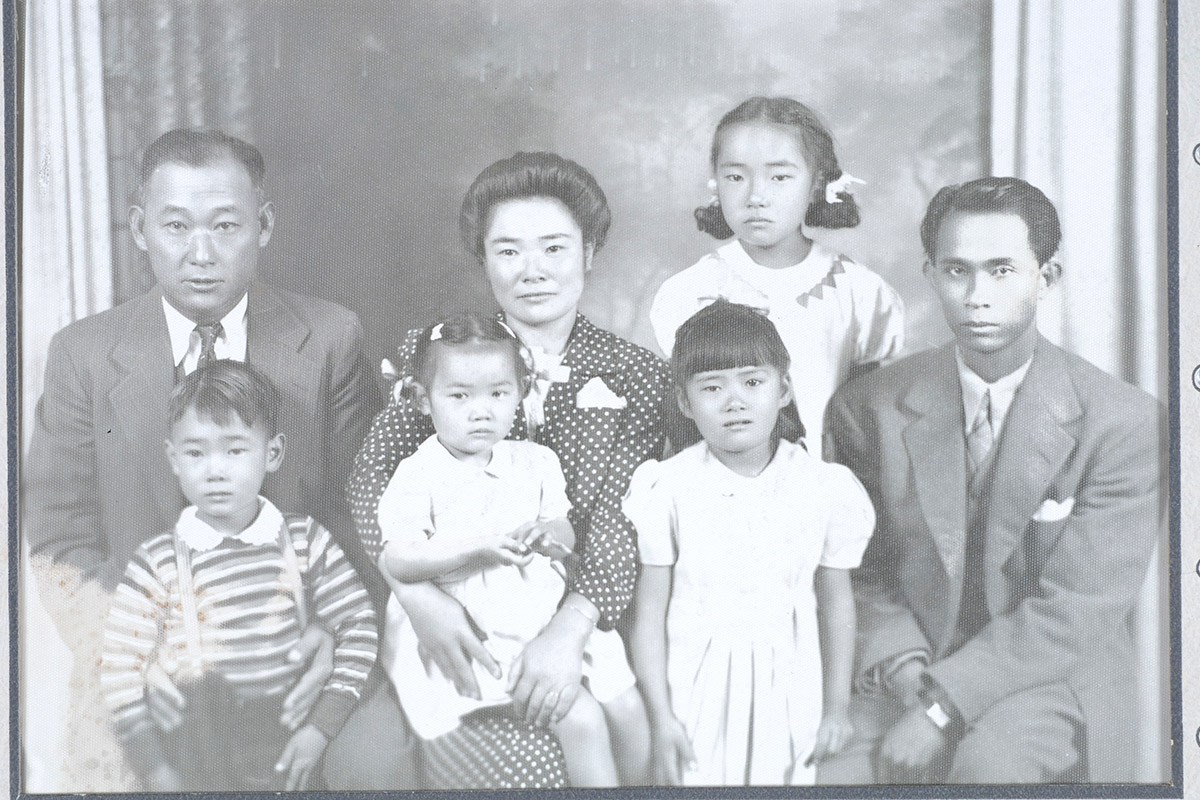

This is one of two water towers that served Minidoka. Water pumped to the towers from four wells was distributed to mess halls and the lavatory/laundry buildings in each block. August 18, 1942. (WRA photo. National Archives) Shigeko Kitamoto, Nobuko Hayshida, and Fumiko Hayashida, all from Bainbridge Island, were eager to reunite with their sister, Fujio Arima of Seattle, in Minidoka. Fujio's husband was interned and she was left to care for her five young children. Here Fumiko, Nobuko, Fujio, and all of their children (cousins) get together for the first time since the Bainbridge Islanders arrived in Minidoka.

Shigeko Kitamoto, Nobuko Hayshida, and Fumiko Hayashida, all from Bainbridge Island, were eager to reunite with their sister, Fujio Arima of Seattle, in Minidoka. Fujio's husband was interned and she was left to care for her five young children. Here Fumiko, Nobuko, Fujio, and all of their children (cousins) get together for the first time since the Bainbridge Islanders arrived in Minidoka. Visits such as this one occurred in all of the camps. Young men were fighting for freedom abroad while their family and friends were denied their freedom back home. Left to right: Miyoko Mikami, Kay Sakai Nakao, Kazuo Ogawa, Toshiko Mikami, Kikuno Mikami Ogawa, Akira Shibukawa, Mamoru Shibukawa.

Visits such as this one occurred in all of the camps. Young men were fighting for freedom abroad while their family and friends were denied their freedom back home. Left to right: Miyoko Mikami, Kay Sakai Nakao, Kazuo Ogawa, Toshiko Mikami, Kikuno Mikami Ogawa, Akira Shibukawa, Mamoru Shibukawa. Photographed while visiting their mother in Minidoka. Left to right: Masakatsu (442), Setsuo (442), and Taketo (med-tech)

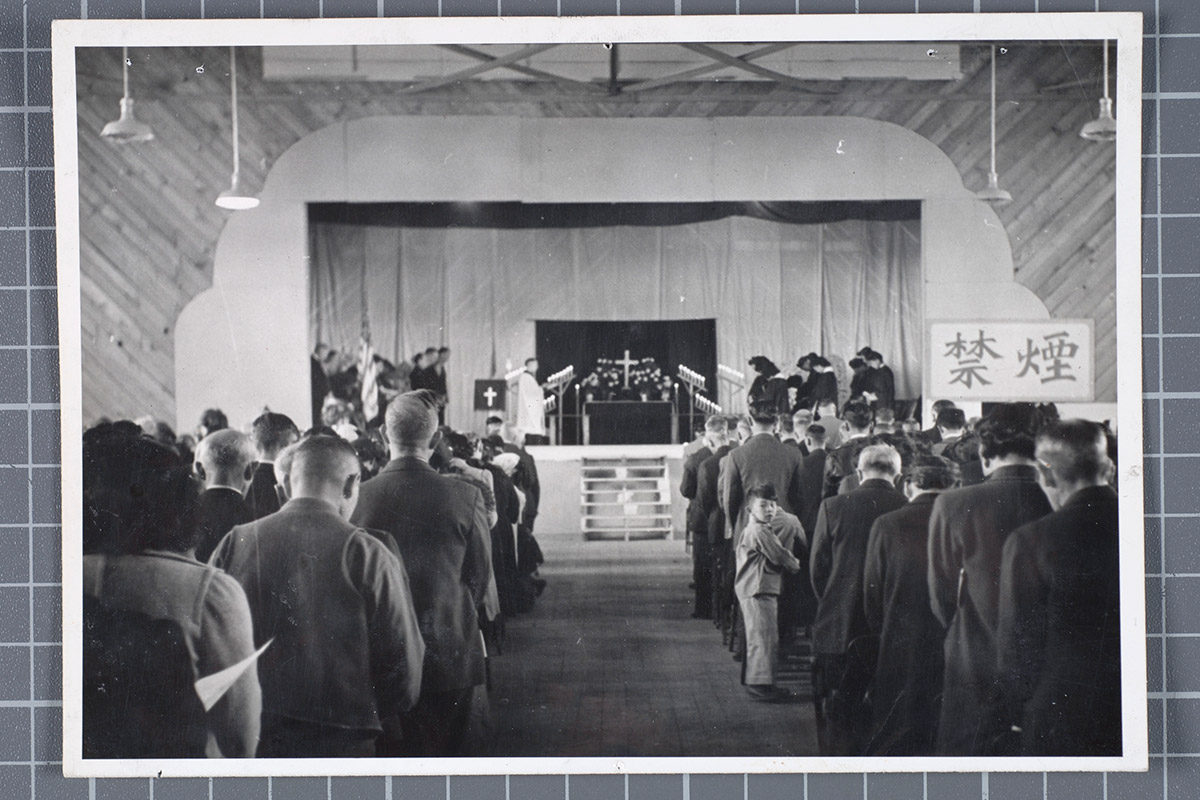

Photographed while visiting their mother in Minidoka. Left to right: Masakatsu (442), Setsuo (442), and Taketo (med-tech) Held in the Hunt High School Gymnasium inside Minidoka, this was a combined Protestant, Catholic, and Buddhist service.

Held in the Hunt High School Gymnasium inside Minidoka, this was a combined Protestant, Catholic, and Buddhist service. July 1, 1943. Many Issei (first generation Japanese Americans) occupied themselves with English classes as well as other hobbies such as sewing, painting, furniture building, and gardening.

July 1, 1943. Many Issei (first generation Japanese Americans) occupied themselves with English classes as well as other hobbies such as sewing, painting, furniture building, and gardening. March 1944. Nobuko Sakai, Bruce Nakao, Kay Sakai Nakao, Taeko Sakai. Kay and Sam Nakao were married in Twin Falls, Idaho. They were farmhands outside of camp for a while then returned to Minidoka for the birth of their first child, Bruce.

March 1944. Nobuko Sakai, Bruce Nakao, Kay Sakai Nakao, Taeko Sakai. Kay and Sam Nakao were married in Twin Falls, Idaho. They were farmhands outside of camp for a while then returned to Minidoka for the birth of their first child, Bruce. Yasuko Hayashida and Hideko Kitamoto, taking Japanese classical dance lessons in Minidoka. This was another past time that young Islanders took part in to occupy themselves in camp.

Yasuko Hayashida and Hideko Kitamoto, taking Japanese classical dance lessons in Minidoka. This was another past time that young Islanders took part in to occupy themselves in camp. The youngest occupants of the camp have the happiest memories. They had plenty of friends to play with and lots of space to run around in. It is a testament to their protective parents that many of them do not have bad memories to this time.

The youngest occupants of the camp have the happiest memories. They had plenty of friends to play with and lots of space to run around in. It is a testament to their protective parents that many of them do not have bad memories to this time. Yoshikazu Kitamoto's preschool class at Minidoka. Yoshikazu is in the front row, second from left.

Yoshikazu Kitamoto's preschool class at Minidoka. Yoshikazu is in the front row, second from left. Hiro was chosen to take part in a horse demonstration performed for his elementary school. The children are outside Stafford Elementary school located in Minidoka.

Hiro was chosen to take part in a horse demonstration performed for his elementary school. The children are outside Stafford Elementary school located in Minidoka. Neal Hayashida, Susan Hayashida, and Yoshikazu Kitamoto, all cousins, play together outside of their family’s barracks. Wooden planks that served as a walkway for wet and muddy days can be seen on the ground.

Neal Hayashida, Susan Hayashida, and Yoshikazu Kitamoto, all cousins, play together outside of their family’s barracks. Wooden planks that served as a walkway for wet and muddy days can be seen on the ground. Yoshikazu Kitamoto, in front, wearing the soldier's uniform loved to dress up in. His mom ordered several different costumes for him from a catalog store.

Yoshikazu Kitamoto, in front, wearing the soldier's uniform loved to dress up in. His mom ordered several different costumes for him from a catalog store. Left to right: Yuriko Kitamoto, Yoshikazu Kitamoto, Chiseko Kitamoto, unknown. These children are playing in gardens outside their barracks that their parents planted.

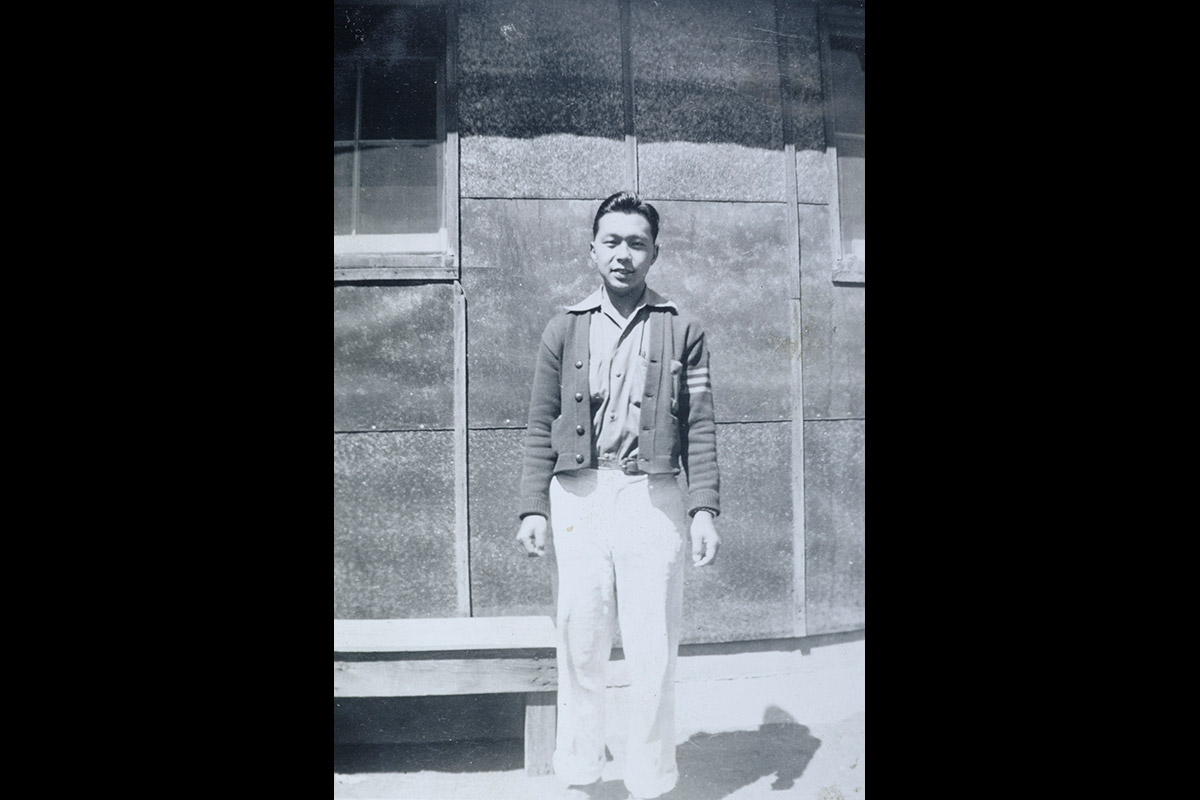

Left to right: Yuriko Kitamoto, Yoshikazu Kitamoto, Chiseko Kitamoto, unknown. These children are playing in gardens outside their barracks that their parents planted. Kete, class of 1941, is still showing his Bainbridge Island High School spirit by sporting his letterman's sweater in Minidoka.

Kete, class of 1941, is still showing his Bainbridge Island High School spirit by sporting his letterman's sweater in Minidoka. They are standing in front of Masa's apartment in Minidoka as indicated by the nameplate on the barracks behind them.

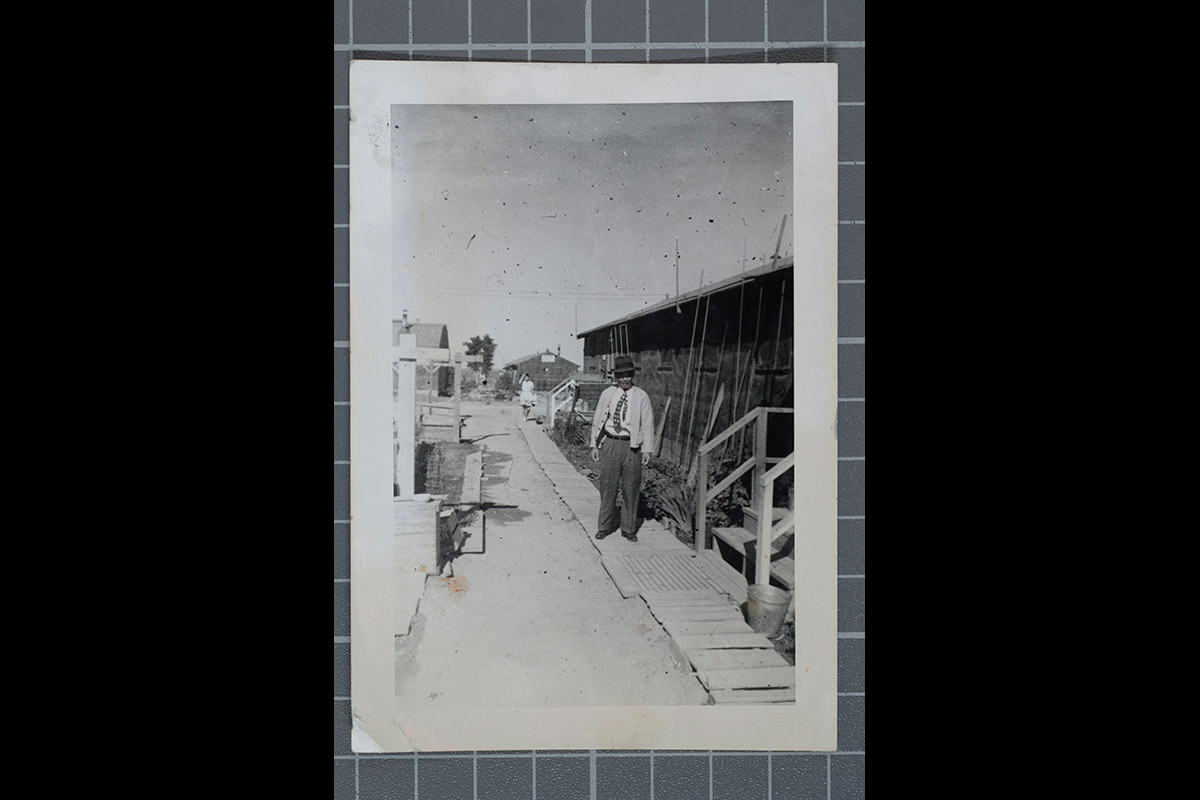

They are standing in front of Masa's apartment in Minidoka as indicated by the nameplate on the barracks behind them. This photo was taken towards the end of the war. The gardens are lush and well established and the walkway has been well used.

This photo was taken towards the end of the war. The gardens are lush and well established and the walkway has been well used. Tsuneichi, age 34, was a bachelor who lived with his two brothers and their families before the war on Bainbridge Island. During the war he eventually left camp to work as a farmhand. After the war he and his older brother, Ichiro, returned to Bainbridge to resume farming.

Tsuneichi, age 34, was a bachelor who lived with his two brothers and their families before the war on Bainbridge Island. During the war he eventually left camp to work as a farmhand. After the war he and his older brother, Ichiro, returned to Bainbridge to resume farming. Ichiro Hayashida made this bar and seesaw in between the barracks at Minidoka for the kids to play on. Here an older boy is exercising.

Ichiro Hayashida made this bar and seesaw in between the barracks at Minidoka for the kids to play on. Here an older boy is exercising. Ichiro, age 26, was one of they young Nisei, second generation Japanese American, who became a leader both on Bainbridge Island before evacuation and in camp. He helped communicate with the government on behalf of the community before evacuation, even petitioning, unsuccessfully, to allow some of the farmers remain behind to harvest their crops.

Ichiro, age 26, was one of they young Nisei, second generation Japanese American, who became a leader both on Bainbridge Island before evacuation and in camp. He helped communicate with the government on behalf of the community before evacuation, even petitioning, unsuccessfully, to allow some of the farmers remain behind to harvest their crops. The Islanders often enjoyed outings to the canal, which ran along the northern border of the camp. Left to right: Yasuko Hayashida, Hisako Hayashida, Toyoko Hayashida, Masu Okazaki.

The Islanders often enjoyed outings to the canal, which ran along the northern border of the camp. Left to right: Yasuko Hayashida, Hisako Hayashida, Toyoko Hayashida, Masu Okazaki. Picnicking on canal at Minidoka.

Picnicking on canal at Minidoka. Left to right: Yuriko Kitamoto, Jane Nakamura, Toyoko Hayashida, Hisako Hayashida, Kayo Hayashida, Yoshiko Matsushita, Hiroshi Hayashida, Fumiko Hayashida, Leonard Hayashida, Mamoru Hayashida, Yasuko Hayashida, Yoshikazu Kitamoto, Hideko Kitamoto

Left to right: Yuriko Kitamoto, Jane Nakamura, Toyoko Hayashida, Hisako Hayashida, Kayo Hayashida, Yoshiko Matsushita, Hiroshi Hayashida, Fumiko Hayashida, Leonard Hayashida, Mamoru Hayashida, Yasuko Hayashida, Yoshikazu Kitamoto, Hideko Kitamoto Pocatello, ID. Left to right: Back: Frank Sr., Shigeko, Yuriko, Felix. Front: Yoshikazu, Chiseko, Hideko, Felix Narte. Felix and his cousin Elaulio Aquino watched after the Kitamoto farm and home during the war. Felix drove to Minidoka to visit the Kitamotos. This photo was taken during this trip.

Pocatello, ID. Left to right: Back: Frank Sr., Shigeko, Yuriko, Felix. Front: Yoshikazu, Chiseko, Hideko, Felix Narte. Felix and his cousin Elaulio Aquino watched after the Kitamoto farm and home during the war. Felix drove to Minidoka to visit the Kitamotos. This photo was taken during this trip. Yuriko is standing in front of her father's truck that was driven from Bainbridge Island by their friend Felix Narte.

Yuriko is standing in front of her father's truck that was driven from Bainbridge Island by their friend Felix Narte. The Hayashidas take one last photo at the gate to Minidoka before they leave for the trip home to Bainbridge Island. Left to right. Back: Fumiko, Tomiko, Nobuko, Ichiro. Front: Mamoru, Yasuko, Toyoko, Hisako, Hiroshi.

The Hayashidas take one last photo at the gate to Minidoka before they leave for the trip home to Bainbridge Island. Left to right. Back: Fumiko, Tomiko, Nobuko, Ichiro. Front: Mamoru, Yasuko, Toyoko, Hisako, Hiroshi.

Oral History

- Manzanar barracks, work, rec hall, picnics - Michi Noritake (OH0009)

- Manzanar arrival, food, winds - Vic Takemoto (OH0016)

- Manzanar first days, basic facilities, cleaning house - Kay Nakao (OH0022)

- Manzanar food - Iku Watanabe (OH0024)

- Minidoka freedom in camp - Tats Kojima (OH0028)

- Manzanar first day, initial reactions - Yae Yoshihara (OH0037)

- Manzanar becoming Christian, 7–Ups, riot - Yae Yoshihara (OH0038)

- Manzanar/Minidoka Twin falls, nurse's aide, swim in canal - Yae Yoshihara (OH0039)

- Manzanar Loyalty Questionnaire, camp conditions - Frank Kitamoto (OH0044)

- Minidoka oil furnace, spit wads, smoking - Frank Kitamoto (OH0045)

- Minidoka playtime - Hisa Matsudaira (OH0050)

- Manzanar poor conditions - Nobi Omoto (OH0054)

- Manzanar barracks and bathrooms - Matsue Watanabe (OH0065)

- Manzanar school - Matsue Watanabe (OH0066)

- Manzanar, Mother worked in kitchen - Matsue Watanabe (OH0067)

- Manzanar family life got distorted - Sally Kitano (OH0071)

- Manzanar snakes - Sally Kitano (OH0076)

- Manzanar Jello Party - Sally Kitano (OH0077)

- Camp correspondents and column in The Review - Mary Woodward (OH0086)

Photo Information: Manzanar Relocation Center Sign — Wooden sign at entrance to the Manzanar War Relocation Center with a car at the gatehouse in the background. 1943. Copyright: Ansel Adams Collection